Utilizing Enzymatic and Chemical Delignification Methods on Fibrous Plants for Decentralized Production of Absorbent Materials for Menstrual Pads in Semi-Arid Regions

Abstract¶

Over 500 million women suffer from period poverty from around the world. These women lack adequate menstrual pads that are both affordable and efficient and instead resort to unsanitary solutions, such as rags and goat skin. Currently, traditional sanitary pads are primarily composed of cotton. Though they have exceptional absorbency, cotton-based pads are less sustainable in regions that do not traditionally grow cotton, leading to higher costs and scarcity. Previously, sisal fibers were tested to find an alternative material for cotton. The findings showed that sisal fibers had a higher absorbency than cotton. This study explores the viability of using biodegradable materials—pineapple and sisal fibers— that are found in locations that do not locally grow cotton. These fibers are used as sustainable alternatives for making menstrual hygiene products. By also going through experimental methods with sisal, the results were compared. These fibers were modified through the processes of decortication followed by enzymatic and chemical delignification to enhance their absorbent properties. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy and ABTS assays were conducted to assess changes in chemical composition. Absorbency tests were designed to compare the absorbency of treated sisal and pineapple fibers against conventional cotton. The results show that pineapple and sisal fibers achieve absorbency levels nearing cotton with appropriate processing. This research supports the development of eco-friendly menstrual products composed of pineapple and sisal fibers that are accessible and effective, contributing to a sustainable solution for managing menstrual health in resource-limited settings.

Introduction¶

Women comprise half of the world’s population and undergo the menstrual cycle, which they must properly manage. Sanitary products help accomplish this management by absorbing menstrual blood. When it comes to monthly bleeding, women select from a variety of menstruation products based on criteria like affordability, accessibility, and safety. Unfortunately, not all women worldwide have unconditional access to menstrual products. It is estimated that 500 million women have difficulty obtaining menstrual products Kaur et al., 2018. Period poverty refers to the lack of any negative consequences that come with inadequate management of the menstrual cycle, which includes women turning to makeshift remedies, which pose critical health concerns Harrison & Tyson, 2022. These materials include old garments, paper, cotton, wool scraps, goat skin, mattress fragments, and leaves, which do not have reliable absorbency and will often leave stains on outer clothing. This can discourage girls and women from going to school and work, which may endanger the financial security of their families UNICEF, 2023. Given this, it is particularly challenging for women to maintain good menstrual hygiene in low and even middle-income countries where period poverty is prominent. A common product is cotton-based pads, which present problems regarding cost and environmental impact. Although cotton is a versatile plant growing in various regions, some countries lack industrial areas to produce cotton menstrual pads commercially. This causes a high cost for cotton-based pads in these regions as they import them from other countries. Considering that women use 6–8 menstrual pads on average per cycle— which adds up to about 125 kg of menstrual waste— it is essential to remember that most disposable menstrual pads have a breakdown time of 500–800 years for each pad Angeli et al., 2022. Additionally, due to the limited private changing facilities, inadequate sanitation infrastructure, and a lack of disposal options, hygiene products are also disposed of in open spaces or latrines to avoid shame Elledge et al., 2018. All of these factors contribute to environmental pollution. To overcome these challenges, this research project explored a natural, biodegradable process for the production of menstrual pads. Fibers from pineapple and sisal grown in rural areas can be used as an alternative material for menstrual pads. These fibers are hydrophilic since hydroxyl and other oxygen-containing groups in the cell wall promote moisture absorption through hydrogen bonding and are responsible for their high absorption capacity Etale et al., 2023. Furthermore, the diameters of these fibers vary in response to changes in moisture content; when moisture content rises, the fibers expand until they saturate, at which point they stop growing further Angeli et al., 2022. These plants are chosen not just for their superior absorbing qualities but also for their resilience and the comparatively low environmental effect of their processing and cultivation. In addition, because these plants are frequently found and grown in rural regions, the production of the menstrual pads can be localized, which lowers expenses compared to commercial menstruation pads, which are produced and imported from foreign countries Foster & Montgomery, 2021. This research seeks to innovate in the field of biodegradable materials and aims to significantly improve accessibility to menstrual hygiene products, thereby addressing both environmental concerns and social inequalities. This work will contribute to a sustainable and equitable world where menstrual health is managed with dignity and without detriment to the environment.

Materials and Methods¶

Decortication¶

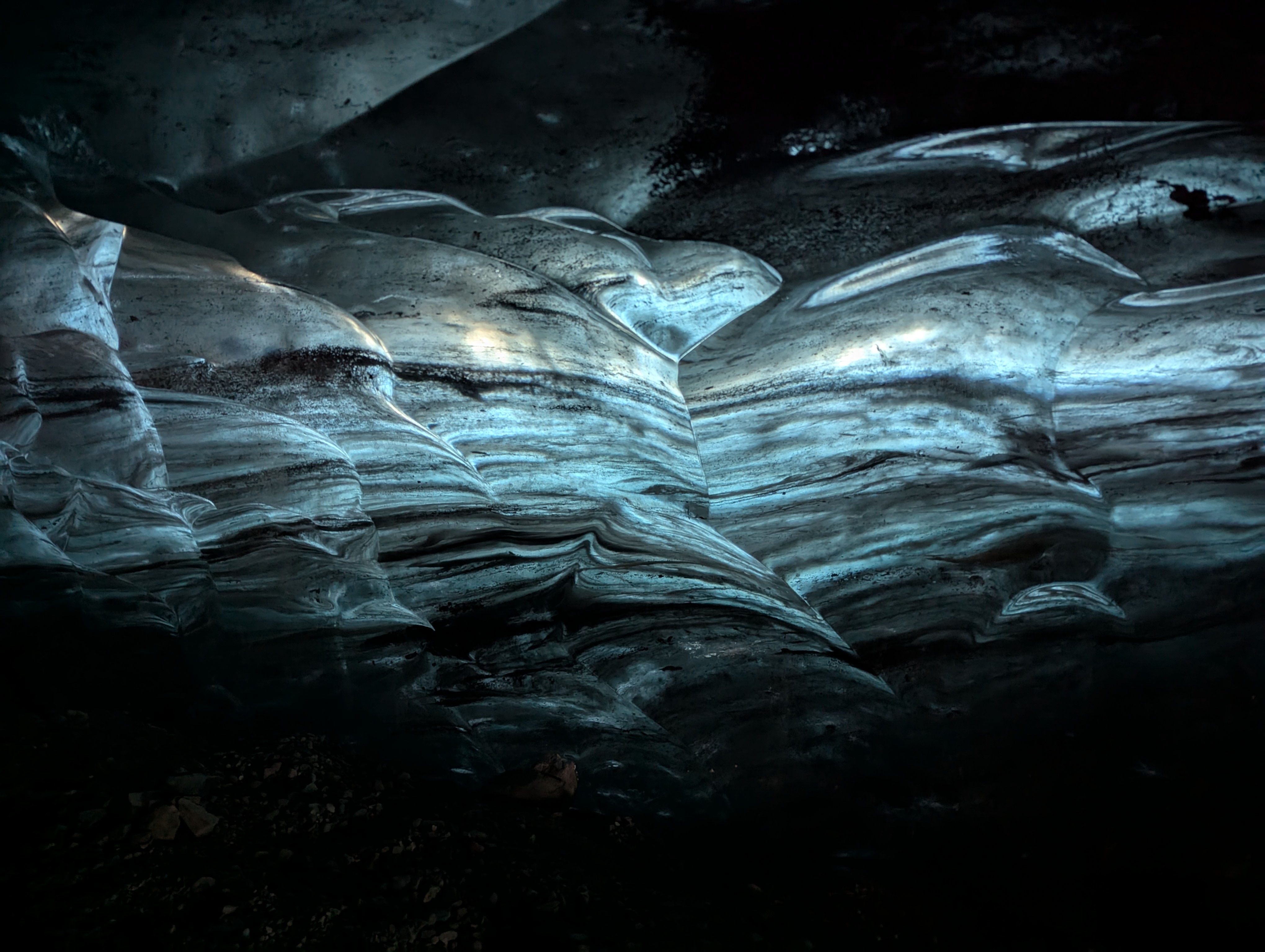

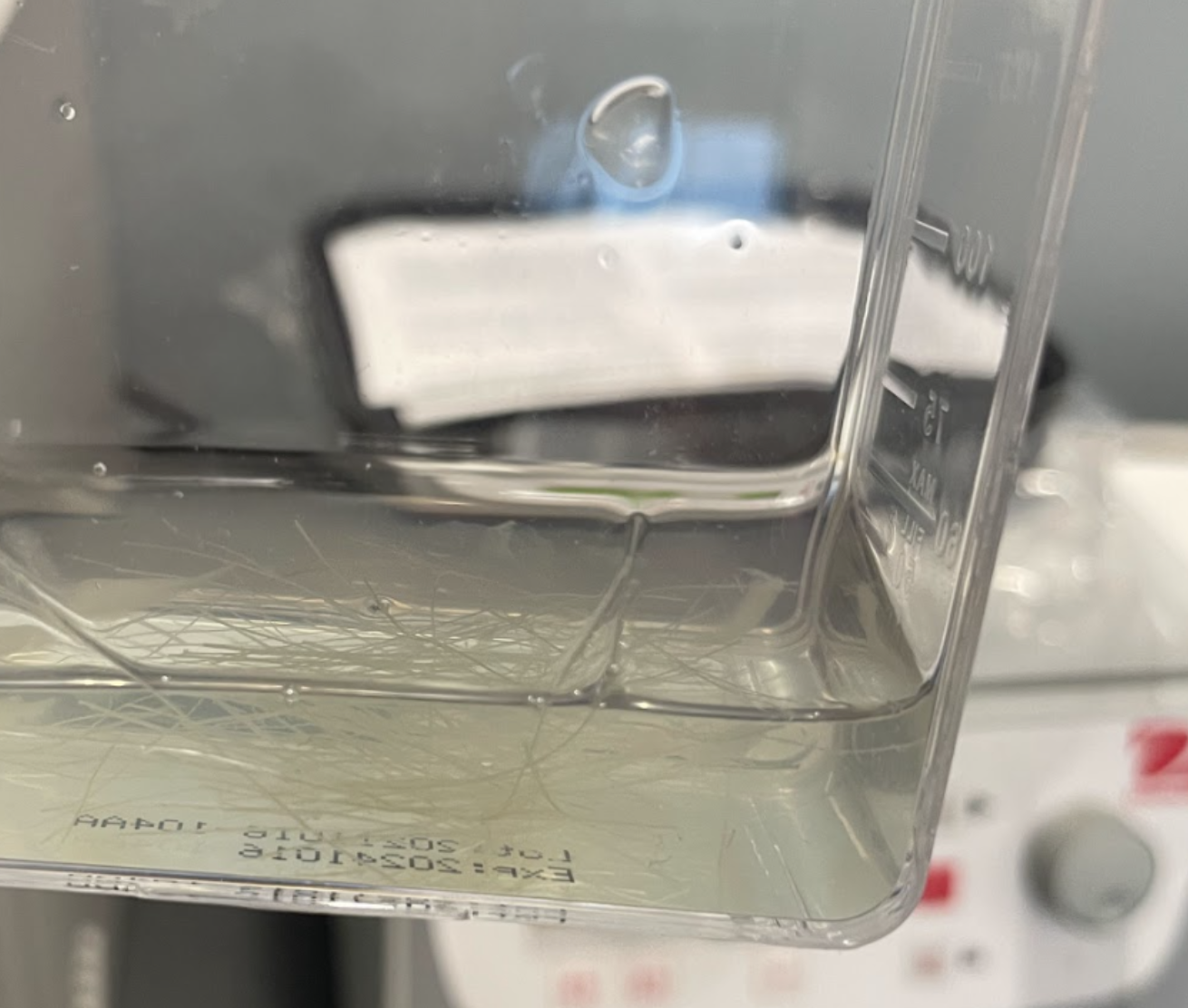

Decortication pertains to the process of removing the outer layer or covering of a structure. The sisal fibers used in the experiment were already decorticated; however, the pineapple fibers had to be manually decorticated when conducting preliminary tests Figure 1. These fibers were then processed by being soaked in a sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and distilled water bath Figure 2. After soaking for five hours, the leaf’s outer layer was stripped with a knife, leaving the fibers behind. These fibers were then sun-dried and saved for later use.

Figure 1:Pineapple leaf in the process of being decorticated

Figure 2:Sodium Hydroxide bath to prepare for decortication

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy¶

FTIR spectroscopy was used to analyze the chemical structure of the fibers throughout the delignification process. This technique is crucial in verifying lignin removal by detecting changes in the functional groups present in the fibers. For the FTIR to properly analyze fibers, they must first be in a powder form. To achieve this, liquid nitrogen was used to freeze the fibers, making them brittle and more accessible to break down in a mortar and pestle. Next, the fibers were ground in a blender to be broken down even further. This powder was then transferred to an oven, which was left at 60 degrees Celsius to eliminate all residual moisture. This step is crucial so there is no chance of hindering the FTIR readings. FTIR spectra analysis occurred after the different delignification methods to see how efficient each method was in removing lignin while preserving the cellulose for absorbency.

Leica ICC50 W¶

To continue reinforcing the findings of delignification, a Leica ICC50 W microscope was used to observe the structural changes of the fibers throughout the experiment. The untreated fibers had a generally larger diameter with rougher surfaces due to debris from parenchymal cells. After usage of PFA, the macrofibers began to unbundle into smaller constituents.

Delignification Preparation¶

Delignification is crucial when working with sisal and pineapple fibers, which are often very stubborn and rigid. Lignin, a natural phenolic polymer with high molecular weight, has a complex composition and structure in the plant cell wall Liu et al., 2018. It consists primarily of three different monolignols: p-coumaric alcohol, coniferyl alcohol, and sinapyl alcohol, which are linked by various types of ether and carbon-carbon bonds Etale et al., 2023. This intricate network contributes to plant cell walls’ rigidity and water resistance. Removing as much lignin as possible is essential when working with these fibers since lignin is hydrophobic and red and uses the fiber’s ability to absorb water. By removing lignin, the cellulose content becomes more accessible, which is crucial for improving the fibers’ mechanical properties. This process also increases the fiber’s porosity and surface area, improving its functionality in various products

Delignification Process¶

The delignification process was carried out in two distinct ways: chemically and enzymatically. The chemical route utilized PFA and followed up with a sodium hydroxide solution. The enzymatic route utilized laccase, an enzyme meant to break down the lignin within the plant fibers, initially from both T. versicolor and P. djamor; however, for the second enzymatic method, only a powder form of T. versicolor was used. Two Pyrex media glasses were utilized; one was for pineapple fibers, and the other was for sisal fibers. Each glass was filled with 50 mL of diluted PFA acid. To do this, 45mL of deionized water is first put into the glassware, then 5 mL of PFA acid is added. This order minimized the risk of splashing during the addition process, ensuring that any potential splash would involve water rather than the more hazardous PFA. Then, 0.5 g of each fiber was placed into its respective glass. These glasses were incubated at 50 degrees Celsius for approximately 48 hours. After two days, the flasks were removed from the incubator, and the fibers were decanted so that the PFA waste could be appropriately disposed of in an amber bottle. Next, the fibers’ pH was neutralized by washing them with deionized water thoroughly, followed by neutralization checks using pH strips. Following this, the fibers went through a sodium hydroxide bath. The NaOH bath is created by diluting 50 mL of 2M NaOH with 50 mL of DI water. 100 mL of 1M NaOH may also be used. The neutralized pineapple and sisal fibers are transferred into two new glassware, each with 50 mL NaOH solution. These two glasses are left to incubate at 50 degrees Celsius for 4 hours. The fibers were gathered after this process, and their pH was neutralized. To let them dry, the fibers were left on a weight tray in an incubator at room temperature for three days Molina et al., 2023. These protocols are appropriate for two samples of fibers, but when more than two are necessary, the chemical ratios must increase proportionally. It is important to note that the chemical methods, while effective, often require harsh reagents and elevated temperatures, which can have adverse environmental impacts and may degrade the fibers’ structural integrity. An enzymatic method was also employed to address these challenges and explore a more sustainable approach. Enzymatic delignification offers several advantages, such as operating under milder conditions and being more environmentally friendly, as it uses natural catalysts, like laccase, to selectively break down lignin without the need for aggressive chemicals. Furthermore, enzymatic methods preserve more cellulose fibers, critical for maintaining the absorbent properties essential for menstrual pads. The first enzymatic delignification process used four flasks. Each flask was filled with 45 mL of miracle grow, adding a 1000 mL pipette tip worth of both P. djamor and T. versicolor fungi. The miracle growth serves as a nutrient solution that promotes the growth and activity of the fungi, ensuring optimal production of laccase enzymes. This is crucial for breaking down the lignin in the fibers. Next, 60mg of pineapple and sisal fibers were added to each flask. This ensured that the experimental setup covered both fibers so that they could be degraded by both fungi. These flasks were incubated at 40 degrees Celsius Banerjee et al., 2019. For the next three days of this assay, qualitative analysis was conducted, and it was found that the laccase enzyme’s degradability was decreasing. To overcome this, Luria broth was added to the flasks to provide additional nutrients and support the sustained growth of the fungi. Luria broth, commonly used in microbial culture, contains essential nutrients like peptides and vitamins that promote robust cell growth.

2,2-azinobis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) method¶

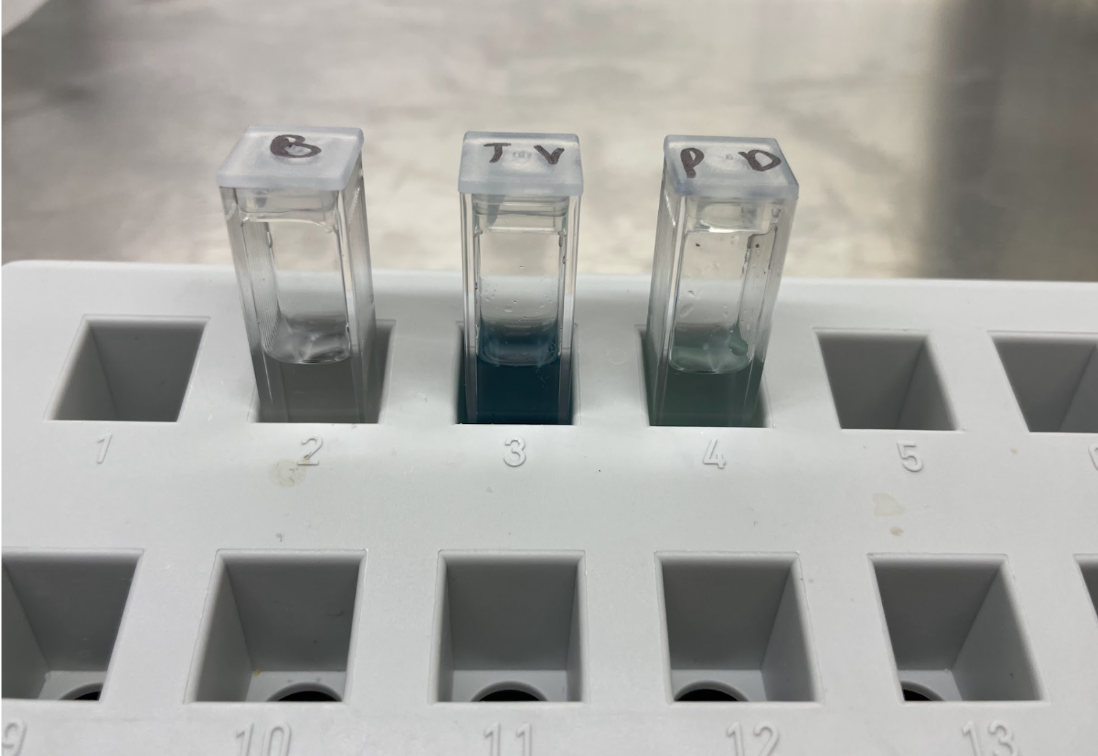

The 2,2-azinobis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) method was used to measure the activity of laccase enzymes in breaking down lignin in the fibers. ABTS acts as a substrate for laccase, and its oxidation by the enzyme leads to a color change, which can be quantitatively measured through spectrophotometry. First, the sodium acetate buffer was diluted from 1.7 mM to 1.0 mM by mixing 2.8 µL of sodium acetate buffer with 5 mL of distilled water. Next, a stock solution of ABTS was prepared by dissolving 1.37 mg of ABTS in the diluted sodium acetate buffer, achieving a final concentration of 0.5 mM. This method used a UV spectrometer for which three cuvettes were prepared. The first cuvette served as a blank control, containing only 1 mL of the sodium acetate buffer without any enzyme to ensure no reaction occurred. The second cuvette was designated for the experimental condition involving Trametes versicolor (TV), containing 1 mL of the fungal culture medium, sodium acetate buffer, and ABTS stock solution.Similarly, the third cuvette was prepared for Pleurotus djamor (PD), using 1 mL of the PD culture medium alongside the buffer and ABTS solution. The volume of the culture medium was adjusted based on initial results to optimize enzyme concentration in each cuvette. After preparing the cuvettes, the spectrophotometer was set to 420 nm to measure absorbance, and readings were taken at 5-minute intervals to track changes in absorbance, which correlate with the activity of the laccase enzyme Li, 2008.

Test Squares¶

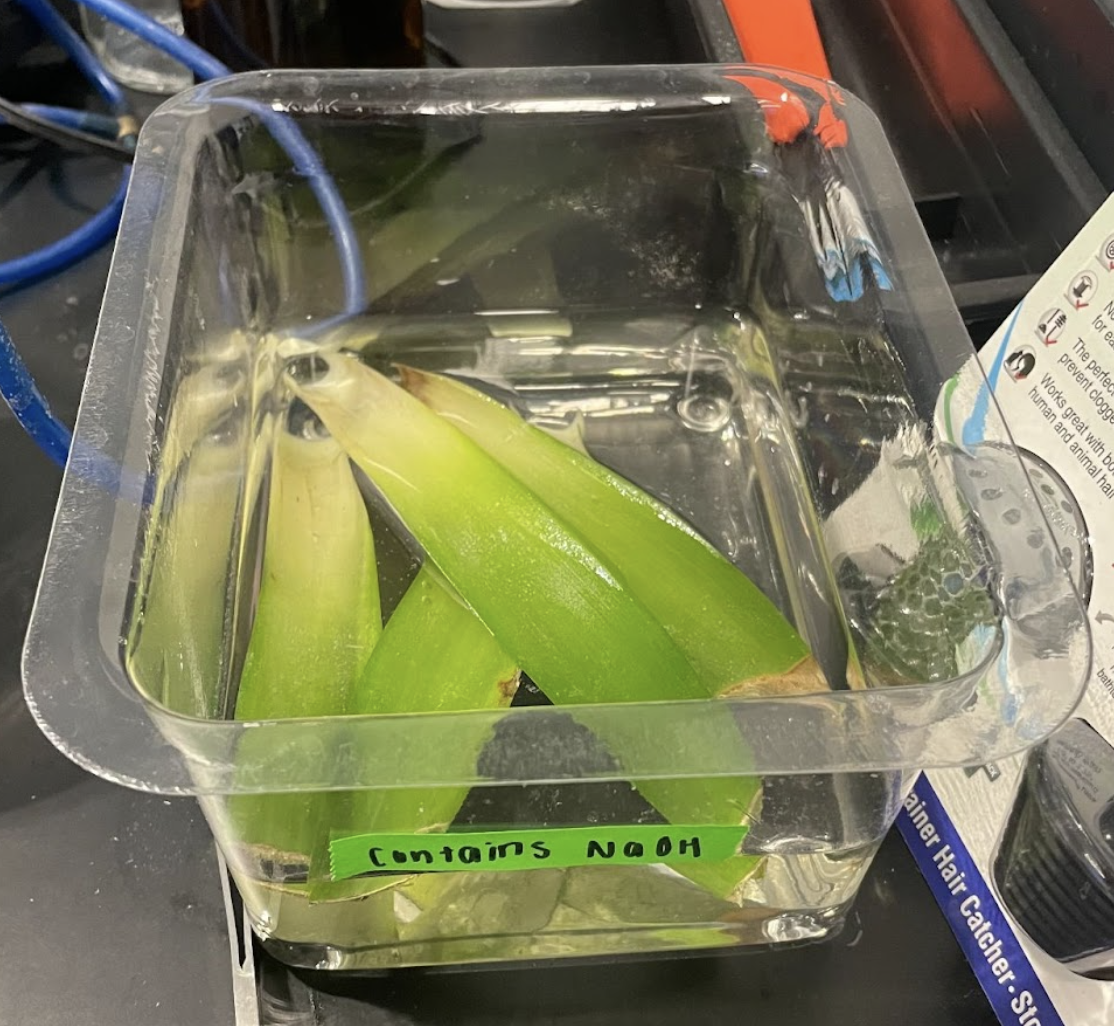

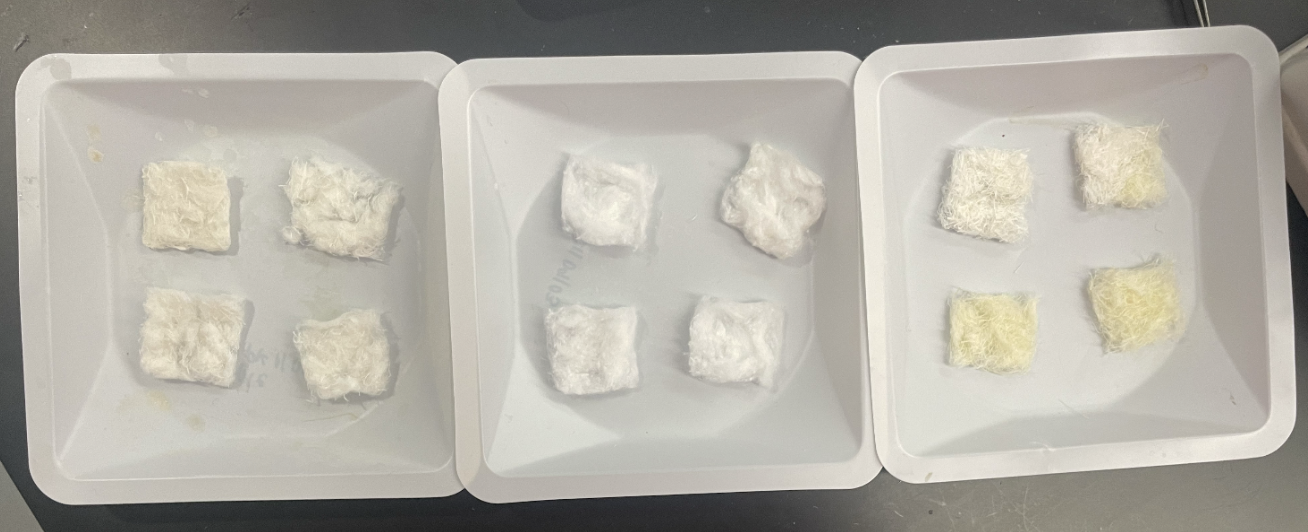

The fibers were first made into test squares to prepare the fibers for the absorbency test. A template measuring 1.25" x 1.25" x 0.25" was 3D printed Figure 3. After delignification, the wet pulp was decanted and left to air dry for three days. After drying, the resulting fluff was dry blended. Once the fluff pulp was fully processed, it was molded into the template to create uniform absorbent pads per the study’s specifications Molina et al., 2023.

Figure 3:3-D printed template

A gelatine solution was prepared to test the absorbency of different fabrics. 2g of gelatine was added to 60 mL of water. The mixture was heated to 60°C while stirring continuously until all gelatine particles had fully dissolved. The solution was then divided into three 20 mL volumes, each allocated for testing cotton, pineapple fiber, and sisal fiber. Before testing, the temperature of each 20 mL volume was checked to ensure it had cooled to room temperature (21°C) to maintain consistent viscosity representative of menstrual fluid. These protocols are appropriate for 3 test fibers. Each fabric sample was weighed using a precision lab scale. The weighted fabrics were placed into containers of the same size. Then, 20 mL of the gelatine solution was poured onto each fabric sample. After 60 seconds, the fabrics were removed from their containers and weighed again to determine the amount of liquid absorbed. The absorption index for each fabric was calculated by taking the ratio of the absorbed mass to the fabric’s dry weight. Foster & Montgomery, 2021.

Results¶

Decortication¶

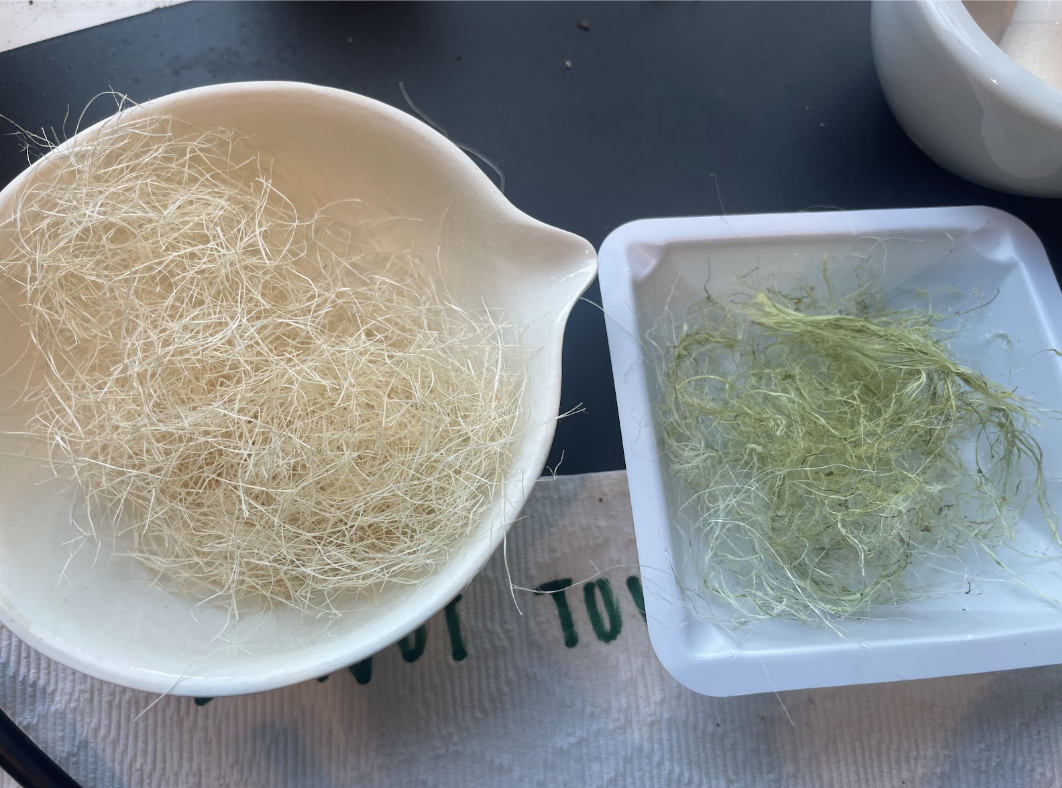

After soaking fibers in a sodium hydroxide and water bath and following it up with scraping with a spoon, if necessary, the fibers came to be separated and softened. Both fibers were prepared for enzymatic and chemical delignification.

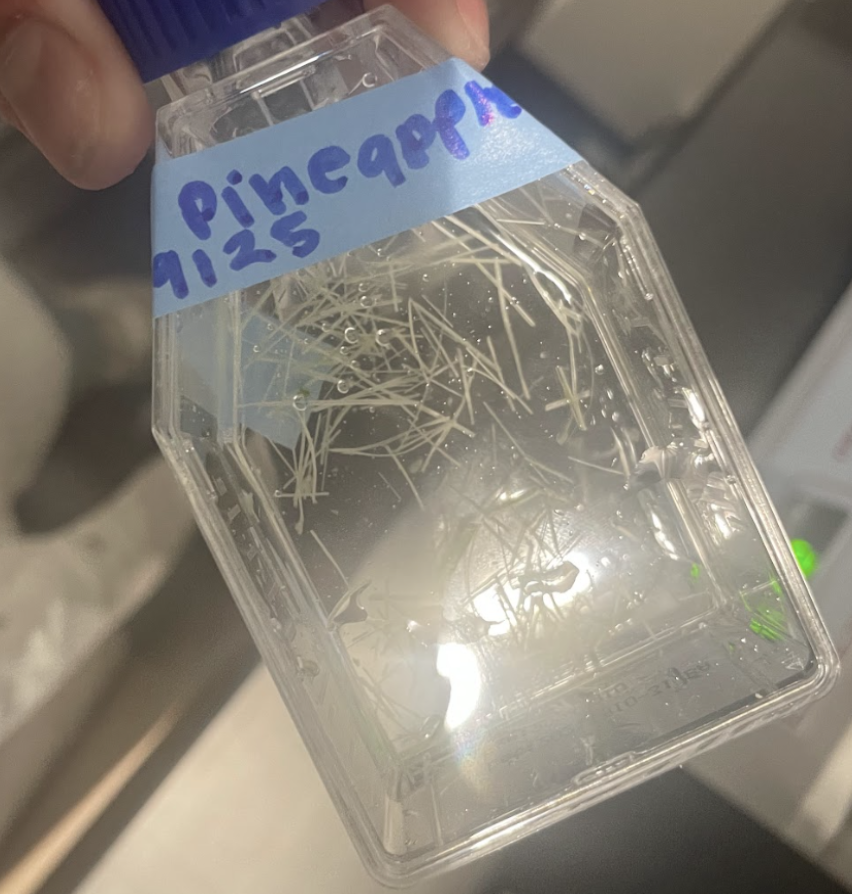

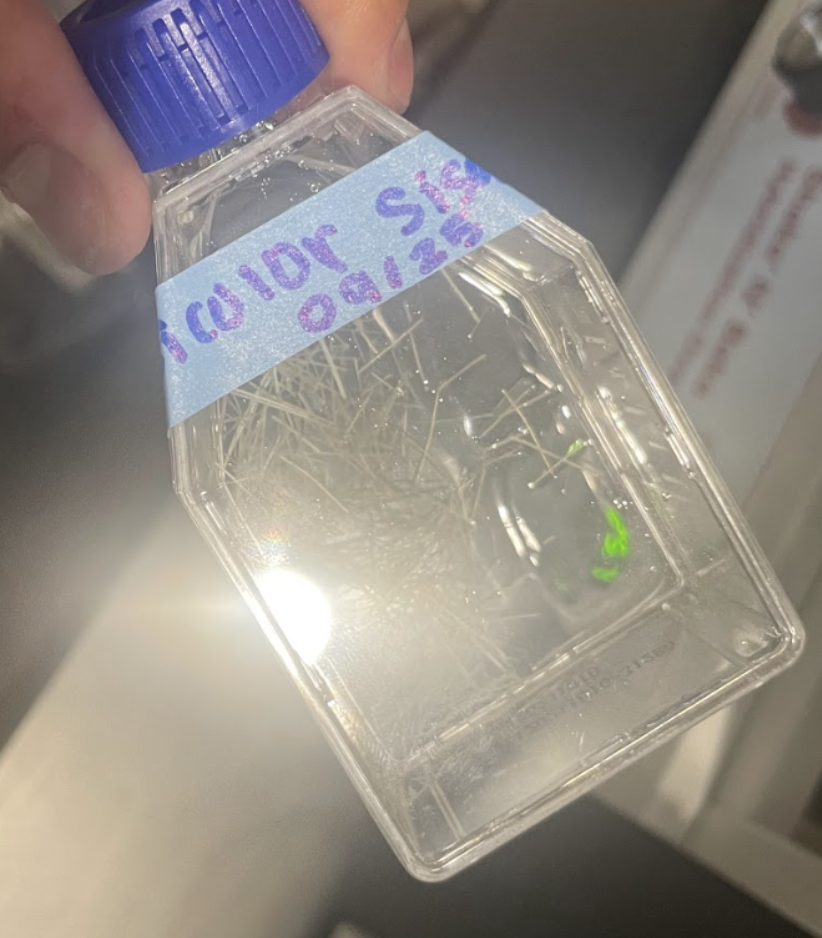

Figure 4:Decorticated fibers (sisal, left; pineapple, right)

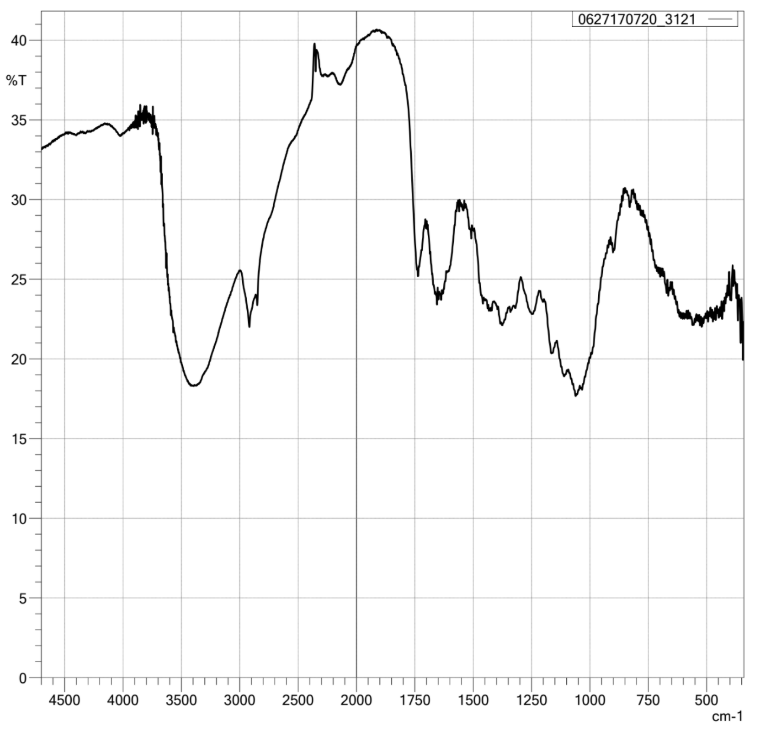

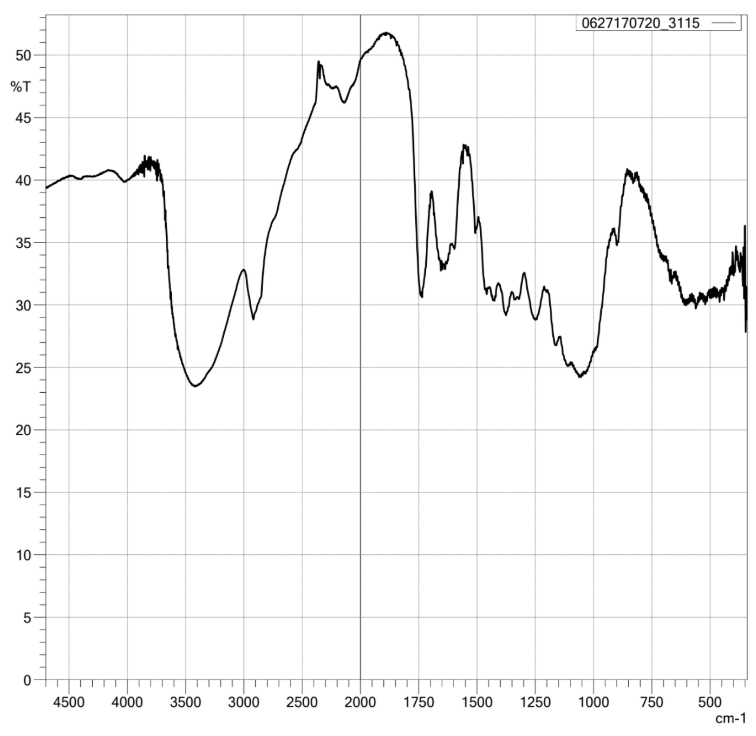

An FTIR spectra was taken immediately after decortication. It is known that there is a high level of lignin in both the sisal and pineapple fibers. However, after the lignin is degraded, the fiber could be mainly composed of cellulose, leading to absorbency similar to cotton.

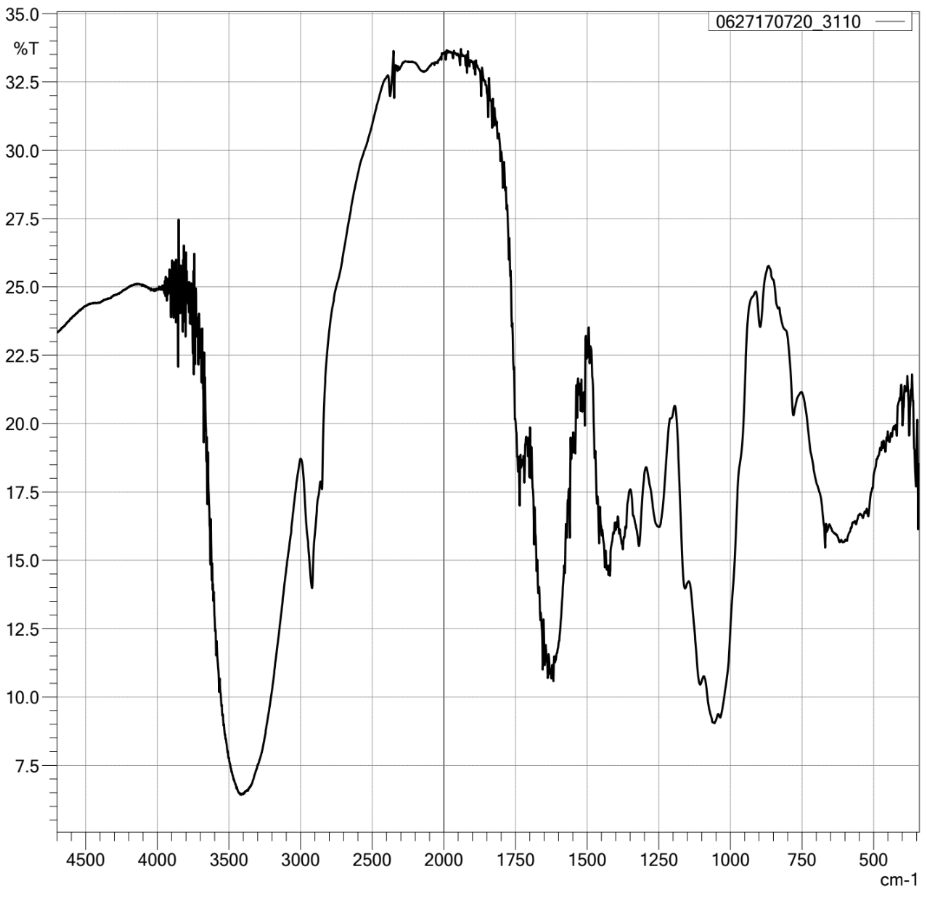

Figure 5:Pineapple fibers pre-treatment FTIR spectra

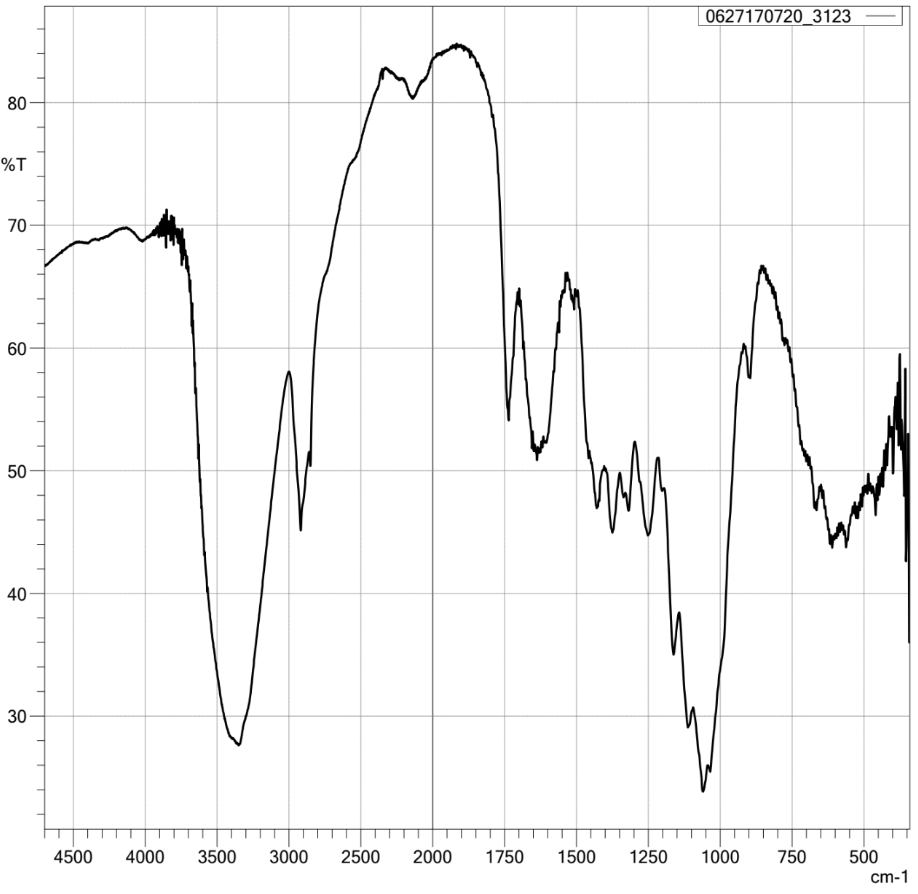

Figure 6:Sisal Fibers pre-treatment FTIR spectra

Above, the FTIR spectra of both fibers prior to delignification are shown. Key absorbance peaks around 1600 cm-1 and 1500 cm-1 show characteristics of aromatic skeletal vibrations typically associated with lignin. These initial observations confirm a significant presence of lignin within the fibers, setting a baseline for assessing the efficacy of subsequent delignification processes.

Delignification & ABTS¶

The fibers went through both the chemical and enzymatic delignification processes and had varying results Figure 7. When chemically delignified, pineapple fibers (left) seemed to have a higher rate as the consistency of the fibers was much more similar to one of cotton. Sisal (right) on the other hand was not as soft since it had small, rigid fibers undelginified.

Figure 7:Delignified fibers

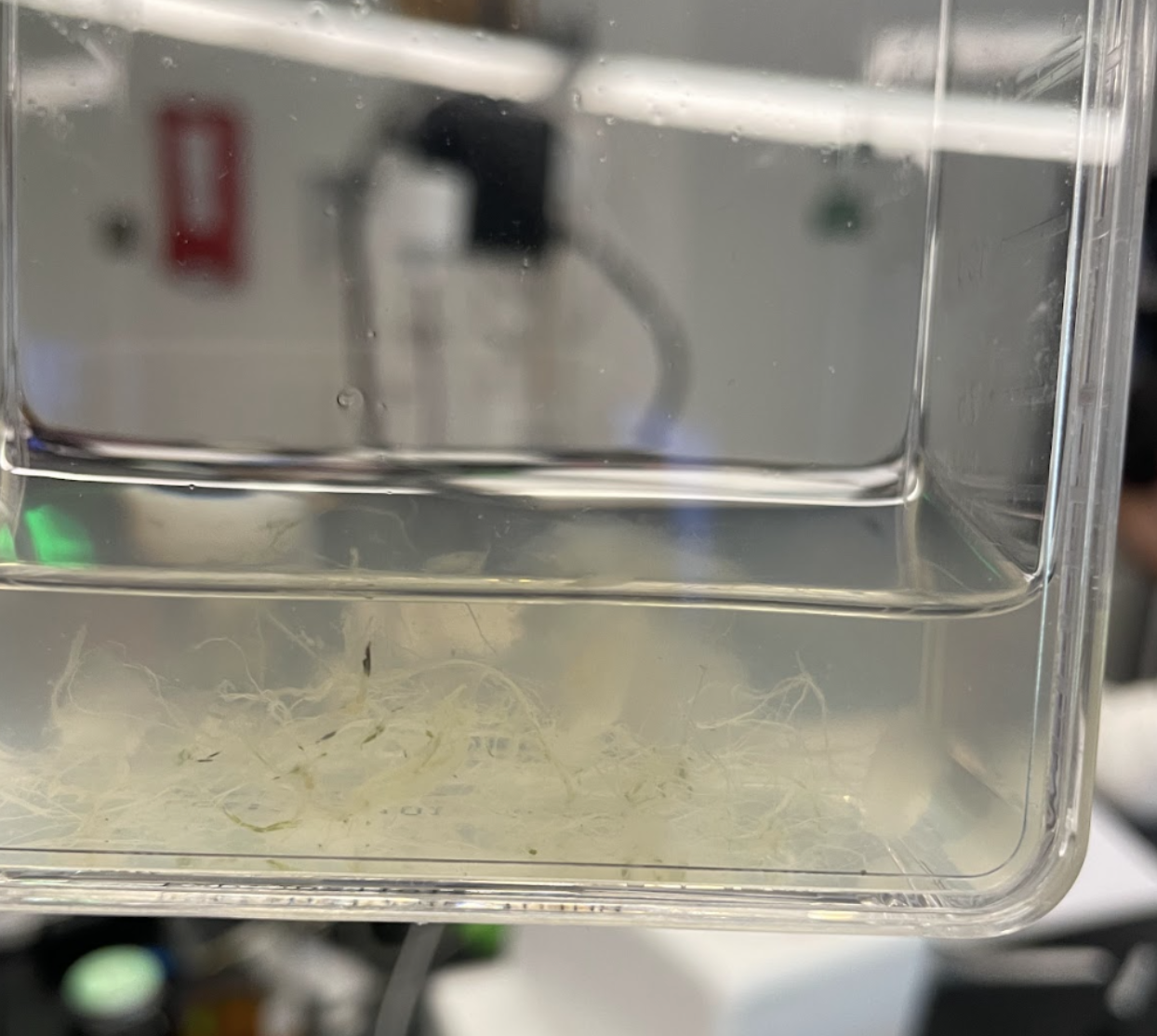

The enzymatic delignification, on the other hand, seemed to have a much slower process when breaking down lignin. The enzymatic delignification was completed by using T.versicolor and P.djamor from a culture. Below are the fibers’ status at their optimal stage of degradation according to the ABTS assay Figure 8 & Figure 9.

Figure 8:Pineapple fibers day 6 of assay

Figure 9:Sisal fibers day 6 of assay

Figure 10:FTIR spectra of pineapple

Figure 11:FTIR spectra of sisal

An FTIR spectra was taken of these fibers to better understand the degradation of lignin shown in these fibers. The analysis of the spectra indicates that there are differences in lignin within the fibers. In the pineapple fiber spectrum, there is a noticeable reduction in the intensity of peaks around 1600 cm-1 and 1500 cm-1, typically associated with the aromatic skeletal vibrations of lignin. The sisal fiber shows similar reductions, though less pronounced, suggesting varying efficiency in lignin degradation between the two fibers or inherent differences in their lignin composition. Additionally, the sisal fiber exhibits slight enhancement of peaks around 1100 cm-1, indicative of C-O stretching in cellulose and hemicellulose, suggesting that the cellulose structure remains intact and functional. The broadening and shifts in the OH stretch region around 3400 cm-1 in both fibers suggest increased hydroxyl group accessibility, likely due to lignin removal, which enhances fiber absorbency. These observations confirm using laccase to selectively degrade lignin without adversely affecting cellulose is crucial for developing biodegradable and absorbent materials suitable for sanitary products. The ABTS assay showed significant enzymatic activity in both T. versicolor and P. djamor cultures. There was a colorimetric change indicating a solid presence of laccase activity. This activity facilitated a noticeable degradation of lignin, particularly in the pineapple fibers, which demonstrated a higher delignification rate than the sisal fibers.

Figure 12:ABTS assay indicator intensity

Additionally, when focusing solely on the activity of the enzyme, the T. versicolor had a darker color change from the indicator than P. djamor Figure 12. The quantitative measurements confirmed that the laccase enzymes from both fungi effectively reduced the lignin content, enhancing the fibers’ potential absorbency for use in menstrual pads.

Figure 13:Rates of Lignin Degradation in Pineapple and Sisal Fibers with T. versicolor vs. P. djamor

The graph above represents the enzymatic delignification effects of T. versicolor and P. djamor on two types of fibers over three consecutive days. T. versicolor exhibits a more pronounced impact on sisal fibers, particularly on the assay’s final day, where the lignin degradation rate peaks significantly compared to other treatments. This suggests a strong adaptability of T. versicolor enzymes towards the cellulose structure of Pineapple fibers, possibly due to better enzyme-fiber interaction or enzyme specificity towards the lignin components of Pineapple fibers. Conversely, P. djamor, while showing consistent activity across both types of fibers, does not reach the degradation rate exhibited by T. versicolor on either fiber. To further understand the significance of this conclusion, p-value tests were conducted. Though both were statistically insignificant as p-values were more significant than 0.05, by conducting more trials, there is potential for a lower p-value would likely be found to prove the differences between the two fungi. This could indicate a different mode of enzymatic action or lower efficiency of P. djamor enzymes in breaking down lignin under experimental conditions. To modify the enzymatic technique in hopes of getting higher rates of delignification, the powder T. versicolor was used rather than the culture. Only T. versicolor was used since it showed more significant delignification than P. Djamor in the ABTS assay. To prepare the enzyme solution for lignin degradation, 10 mg of laccase was dissolved in 10 mL of sodium acetate buffer (pH 4-5) to achieve a stock concentration of 1 mg/mL. The buffer was prepared by mixing 1.443 g of sodium acetate and 0.445 g of acetic acid in 160 mL of distilled water, adjusting the pH to approximately 5.0 with 10N hydrochloric acid (HCl), and then bringing the final volume to 200 mL with additional distilled water. This preparation resulted in a sodium acetate concentration of approximately 1.8 M and an acetic acid concentration of about 0.95 M, based on the provided weight percentages and molar masses. Following buffer preparation, 0.2 g of cut-up fibers from pineapple and sisal were placed into two flasks and labeled accordingly. Each flask then received 10 mL of the enzyme solution. The flasks were incubated at 40-50 degrees Celsius for 36 hours on a shaker or stirrer to facilitate the enzymatic degradation of lignin in the fibers. This method aims to optimize the conditions for effective lignin removal, enhancing the fibers’ potential absorbency Atalla et al., 2013.

Figure 14:Second enzymatic delignification assay pineapple

Figure 15:Second enzymatic delignification assay sisal

Result analysis with the ABTS method and FTIR spectra aided in evaluating the practical implications of the delignification process on the fibers’ usability in real-world applications. Due to lignin removal, the chemically softened fibers displayed enhanced malleability and surface area. This simulated the absorbency characteristics that are essential for high-quality menstrual pads. This step validated the delignification treatment’s effectiveness in mimicking the desirable properties of cotton and provided a benchmark for comparing the functional performance of pineapple and sisal fibers post-treatment. Ultimately, absorbency was performed using the delignified fibers. For this, the softened fibers from chemical degradation were utilized.

Absorbancy Testing¶

Absorption was assessed through the weight of the fibers. The initial dry weight, Wi, and a final wet weight, Wf, to define absolute absorption. By subtracting the initial weight from the final weight, then dividing the difference by the initial weight, the absorption, in grams fluid/grams fiber, can be found.

Figure 16:Pad samples pre Absorption test

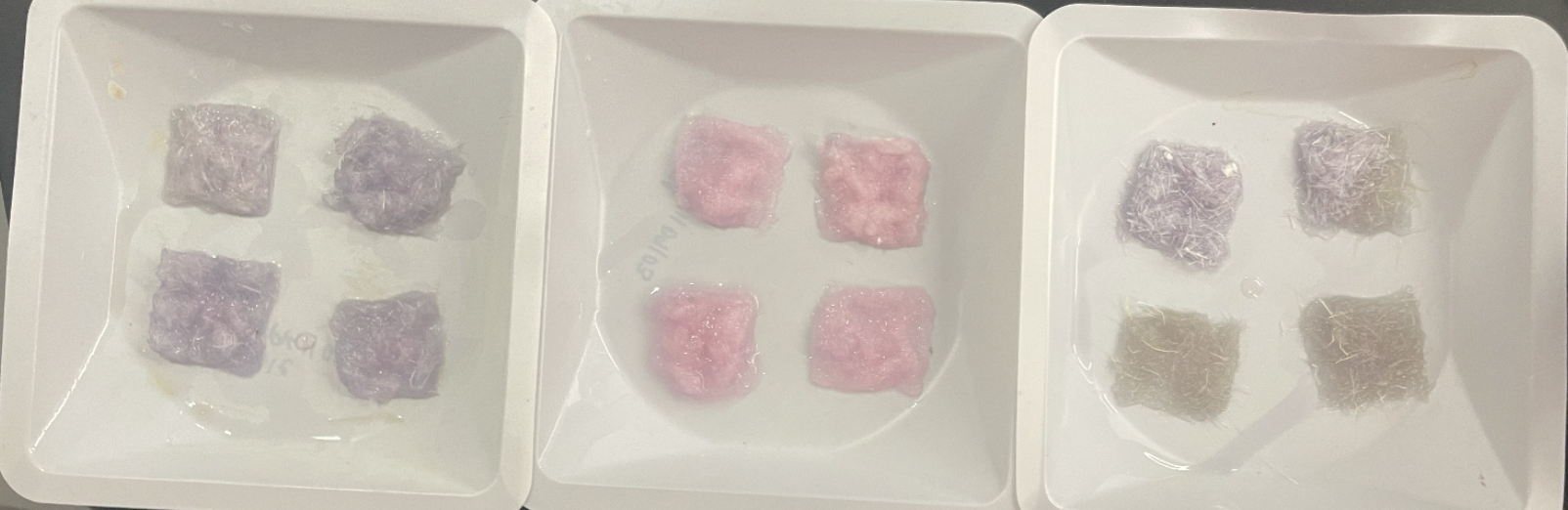

Figure 17:Pad samples post absorption test

Absorption tests conducted over four trials revealed distinct behaviors among pineapple, sisal, and cotton fibers. Throughout all trials, cotton fibers consistently showed high absorbency. They maintained an average absorbency ratio of approximately 95.4 grams fluid/grams square. This high performance is typical of cotton due to its natural properties, including a high degree of crystallinity and a porous structure, which are ideal for absorbing and retaining large amounts of liquid. In comparison, after treatment, pineapple and sisal fibers reached absorbency levels nearing those of cotton, with average ratios of 63.9 and 112.5 grams fluid/grams square, respectively. This performance is significant, demonstrating that with appropriate processing, such as enzymatic treatment, natural fibers like pineapple and sisal can be enhanced to perform at levels competitive with cotton for applications that require high fluid absorption. After conducting a t-test and following up with p-values for the four trials between pineapple and sisal, a p-value of 0.02 was found for cotton and pineapple, 0.381 for cotton and sisal, and 0.054 for sisal and pineapple were found. This is not significant, which means that both pineapple and sisal fibers, after treatment, have comparable levels of fluid absorption, making them similarly effective for applications requiring high absorbency. This convergence in performance underscores the efficacy of the enzymatic treatments used. It suggests that pineapple and sisal fibers could be viable alternatives to cotton in producing eco-friendly, absorbent materials. These findings open potential avenues for using pineapple and sisal fibers in sanitary products.

Table 1:Sisal, cotton, pineapple absorption test grams fluid/grams square

| Trial | Pineapple | Sisal | Cotton |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trial 1 | 46.5 | 72.8 | 94.5 |

| Trial 2 | 57.3 | 102.3 | 100.0 |

| Trial 3 | 73.4 | 123.2 | 90.2 |

| Trial 4 | 78.5 | 151.7 | 96.7 |

| Average | 63.9 | 112.5 | 95.4 |

Figure 18:Sisal, pineapple, cotton absorption test

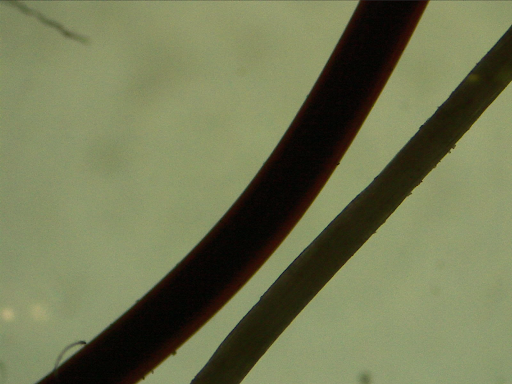

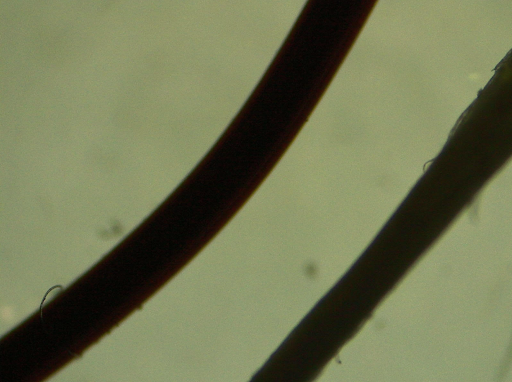

Evaluation of each individual fibers diameter, before and after the delignification process can show the extent of change the fibers have gone through. The swelling of the fiber is indicative of the degree of structural breakdown and increased porosity. Below, Figure 19 & Figure 20 compare a 28 gauge wire with the two fibers, pineapple and sisal, prior to delignification. The 28 gauge wire, on the right, is 0.321 mm in diameter and through using ImageJ’s measurements and cross-sectional area analysis, the pineapple fiber came out to be 0.136 mm while the sisal fiber came out to be 0.145 mm. After delignification Figure 21 & Figure 22 the pineapple fiber came out to be 0.00834 mm while the sisal fiber came to be 0.01468 mm showing a significant reduction in diameter due to the removal of lignin components.

Figure 19:Pre-delignified Pineapple Fiber Compared to 28 Gauge Wire

Figure 20:Pre-delignified Pineapple Fiber Compared to 28 Gauge Wire

Figure 21:Delignified Pineapple Fiber Compared to 28 Gauge Wire. The red circle is indicative of the exact fiber that was measured.

Figure 22:Delignified Sisal Fiber Compared to 28 Gauge Wire. The red circle is indicative of the exact fiber that was measured.

The overall reduction in diameter is 93.87% for the pineapple fiber and 89.87% for the sisal fiber.

Conclusions¶

Delignifying fibers and testing for absorbance from plants found in semi-arid regions is one of the first steps in addressing the crucial issues of period poverty. Using locally sourced, biodegradable materials reduces dependency on non-renewable resources like high-maintenance crops like cotton and offers a cost-effective solution for communities in resource-limited settings. Throughout these experiments, cotton, a commonly used material in menstrual pads, was used as a benchmark. By conducting the ABTS assay, T. versicolor seemed to be a suitable source of laccase, specifically for the fibers used for this project. Although enzymatic delignification was not as successful as chemical delignification, lignin content was still decreased based on the FTIR. Combining laccase activity and decreased lignin concentrations promises improved fiber absorbency and functionality. Additionally, from absorption testing, it was found that both pineapple and sisal fibers reached absorbency levels nearing those of cotton. This implies that the fibers can be competitive with cotton as menstrual pads with enhancement. The diameter comparison through ImageJ allowed for further confirmation of lignin component removal as there was a 93.87% reduction in the pineapple fiber and 89.87% for the sisal fiber.

Discussion¶

The visual examination throughout lignin degradation yielded importance on how the fiber samples react to the varying delignification treatments. For instance, when completing the chemical delignification, the fibers began to look similar to cotton. The comparison to cotton was a visual basis for determining lignin degradation. When the enzymatic delignification occurred, the fibers visually did not look similar to cotton, even after day three passed when the laccase activity peaked. These visual results indicated that a change was necessary. Still, we did not realize that T. versicolor seemed to be the suitable enzyme for these fibers until the ABTS assay was performed. Though quantitative data is crucial, qualitative data yields just as much information. After realizing the sudden shortfall in laccase activity after day three of performing the ABTS method on the initial enzymatic delignification with T. versicolor and P. djmor fungi, it was realized that the laccase enzyme’s degradability was decreasing. To supplement the nutritional deficiency, luria broth was obtained to revive laccase activity; unfortunately, positive results were not shown. Throughout this experiment, FTIR spectra were often taken. Taking these spectra includes crushing up the samples, in this case, the fibers, to the point where it was nearly perfectly homogenized with the KBr used as a matrix for the film within the machine. Unfortunately, these fibers are very stubborn, especially before delignifying. Therefore, despite the pre-FTIR treatment of crushing with mortar and pestle or freezing to make the fibers brittle with dry ice, there may still have been minor errors with the output spectra. Fortunately, the deficit of lignin was still apparent, so perhaps if the reading was more precise, the loss of lignin would have been more drastic. Initially, the intensity of red was to be a determinant of absorbency. Qualitatively, however, after the first trial, a violet shade was observed on the pineapple and sisal fibers post-absorption. This could indicate residual coloration from the test solution, suggesting differences in how these fibers interact with and retain fluid-based substances. So, instead, the difference in weights over the initial weights is the sole factor of absorption efficacy. Additionally, the initial weights of the sisal, pineapple and cotton fibers had disparities given the nature of each pad. Sisal is usually denser and stronger therefore, it has a very high initial weight compared to pineapple and cotton fibers. Pineapple fibers are less dense compared to sisal. Cotton is the least dense therefore it has the lowest initial weight. Substantial room exists for future work. The research findings from the results can be used as a baseline to enhance enzymatic delignification. This will open an environmentally sustainable avenue for developing biodegradable and high-performance menstrual products. Further investigations could focus on optimizing enzyme concentrations and reaction conditions to maximize lignin removal while preserving fiber integrity by conducting mass trials. Additionally, exploring the combination of different types of enzymes, potentially through a synergistic approach, might improve efficiency and cost-effectiveness, making these natural fibers a viable alternative to traditional materials in various consumer products beyond just sanitary pads. Exploring surface tensiometry is also critical as it provides insights into the wettability and spreadability of fluids on fiber surfaces, which is essential for assessing their potential in absorbent applications. Future studies might also explore the scalability of these processes for industrial application, evaluate the long-term environmental impacts of widespread adoption of such fibers, and assess the carbon footprint. Moreover, researching additional natural fibers native to third-world countries could tailor solutions to specific local needs, further expanding the global impact of this sustainable technology.

My sincere gratitude goes to the Research in Biology program at the North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics at Morganton as well as Mrs. Jennifer Williams and Dr. Mareca Lodge.

Copyright © 2024 Kulla. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, which enables reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the creator.

- ABTS

- 2,2'-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid Colorimetric Assay

- FTIR

- Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

- HCl

- hydrochloric acid

- NaOH

- sodium hydroxide

- P. djamor

- Pleurotus djamor

- PD

- Pleurotus djamor

- PDA

- potato-dextrose agar

- PFA

- peroxyformic acid

- T. versicolor

- Trametes versicolor

- TV

- Trametes versicolor

- Kaur, R., Kaur, K., & Kaur, R. (2018). Menstrual Hygiene, Management, and Waste Disposal: Practices and Challenges Faced by Girls/Women of Developing Countries. Journal of Environmental and Public Health, 2018, 1–9. 10.1155/2018/1730964

- Harrison, M. E., & Tyson, N. (2022). Menstruation: Environmental impact and need for global health equity. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 160(2), 378–382. 10.1002/ijgo.14311

- Progress on household drinking water, sanitation and hygiene 2000-2022: Special focus on gender. (2023). https://data.unicef.org/resources/jmp-report-2023/

- Angeli, F., Jaiswal, A. K., & Shrivastava, S. (2022). Integrating poverty alleviation and environmental protection efforts: A socio-ecological perspective on menstrual health management. Social Science & Medicine, 314, 115427. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.115427

- Elledge, M., Muralidharan, A., Parker, A., Ravndal, K., Siddiqui, M., Toolaram, A., & Woodward, K. (2018). Menstrual Hygiene Management and Waste Disposal in Low and Middle Income Countries—A Review of the Literature. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(11), 2562. 10.3390/ijerph15112562

- Etale, A., Onyianta, A. J., Turner, S. R., & Eichhorn, S. J. (2023). Cellulose: A Review of Water Interactions, Applications in Composites, and Water Treatment. Chemical Reviews, 123(5), 2016–2048. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.2c00477

- Foster, J., & Montgomery, P. (2021). A Study of Environmentally Friendly Menstrual Absorbents in the Context of Social Change for Adolescent Girls in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(18), 9766. 10.3390/ijerph18189766

- Liu, Q., Luo, L., & Zheng, L. (2018). Lignins: Biosynthesis and Biological Functions in Plants. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 19(2), 335. 10.3390/ijms19020335

- Molina, A., Kothari, A., Odundo, A., & Prakash, M. (2023). Agave sisalana: towards distributed manufacturing of absorbent media for menstrual pads in semi-arid regions. Communications Engineering, 2(1). 10.1038/s44172-023-00130-y

- Banerjee, R., Chintagunta, A. D., & Ray, S. (2019). Laccase mediated delignification of pineapple leaf waste: an ecofriendly sustainable attempt towards valorization. BMC Chemistry, 13(1). 10.1186/s13065-019-0576-9

- Comparative study on the determination of assay for laccase of Trametes sp. (2008). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228345841_Comparative_study_on_the_determination_of_assay_for_laccase_of_Trametes_sp

- Atalla, M. M., Zeinab, H. K., Eman, R. H., Amani, A. Y., & Abeer, A. A. E. A. (2013). Characterization and kinetic properties of the purified Trematosphaeria mangrovei laccase enzyme. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences, 20(4), 373–381. 10.1016/j.sjbs.2013.04.001