Harvesting Energy with Affordable Piezoelectric Sensors for Low-Power Biosensors

Abstract¶

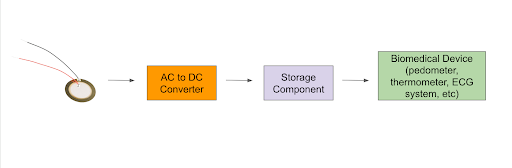

Human body movement-powered technology is the future for biomedical devices. The increased demand for sustainable energy has prompted the exploration of piezoelectric sensors as energy harvesters. This study focuses on the feasibility of using affordable piezoelectric sensors to power low-power biosensors, aiming to reduce reliance on conventional batteries. The research focuses on designing and optimizing a piezoelectric energy harvesting system, examining the relationship between applied pressure and voltage output alongside various energy storage methods, including supercapacitors, rechargeable batteries, and traditional capacitors. The findings of this study contribute valuable insights into piezoelectric power storage, optimizing energy harvesting systems, and affordable piezo technology for devices like thermometers, pedometers, electrocardiograph systems, and more. This study helps pave the way for more efficient self-powered biosensor systems.

Introduction¶

The demand for innovative and sustainable energy solutions is growing rapidly, particularly in the field of biomedical technology, where traditional energy sources, such as batteries, often pose challenges related to limited lifespan, environmental impact, and frequency replacements Al-Rawi et al., 2023. Piezoelectric sensors convert mechanical stress to electrical energy. They have been used to track vitals like heart rate, and their electrical output suggests potential as an alternative to conventional energy harvesting. Despite their potential, the research on the feasibility of using affordable piezoelectric sensors to power biomedical devices is limited.

This study addresses the need for sustainable and cost-effective energy solutions by investigating the feasibility of using piezoelectric sensors in energy harvesting. The objective is to assess its ability to generate power and examine various energy storage methods to optimize efficiency. Through these explorations, the study aims to advance affordable piezoelectric technology for self-powered biomedical devices.

Materials and Methods¶

Selection of Piezoelectric Sensors¶

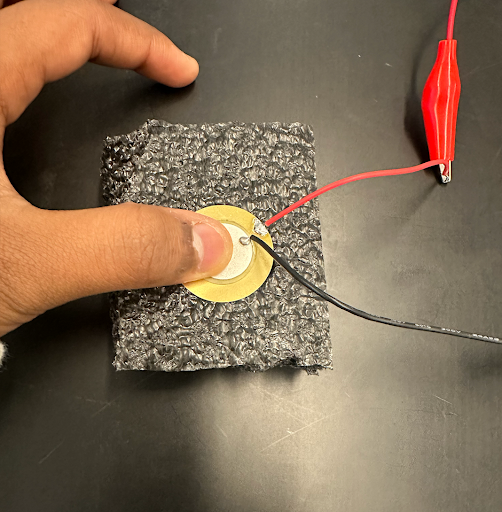

The primary objective was to identify the most efficient and cost-effective piezoelectric sensor for energy harvesting applications. Three sensors were tested: a Disc Sensor see Figure 1, a Ribbon Sensor see Figure 2, and a Flexible Film Sensor see Figure 3. Each sensor was placed on a moving wrist and its voltage output was measured. The sensor that produced the highest and most consistent voltage graph was chosen for further testing.

Figure 1:Piezoelectric Disc Sensor. Image taken from Google Images.

Figure 2:Ribbon Piezoelectric Sensor. Image taken from Google Images.

Figure 3:Piezoelectric Flexible Film Sensor. Image taken from Google Images.

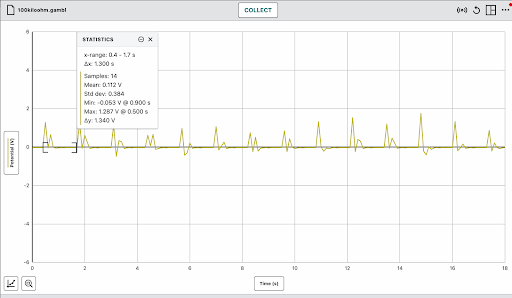

After analyzing the results, the disc sensor was selected for further experimentation due to being the highest voltage output. To optimize its performance, the load resistance was measured to assess the voltage output of the disc sensor, since the correct resistor would maximize the voltage output Niu et al., 2015.

Application of Mechanical Stress¶

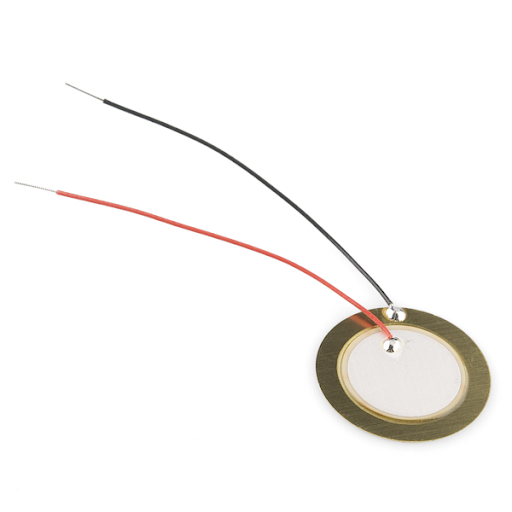

While initial voltage measurements were obtained by attaching sensors to a moving wrist see Figure 5, tapping or pushing on the sensor with the foot or finger see Figure 4 was found to yield higher and more consistent voltage outputs. Tapping or pushing on a “bouncy” surface allows for quick and constant change in the mechanical stress applied to the piezoelectric sensor in the push and release cycles. To further investigate this mechanism, the disc sensor was placed on styrofoam and pushed by the finger.

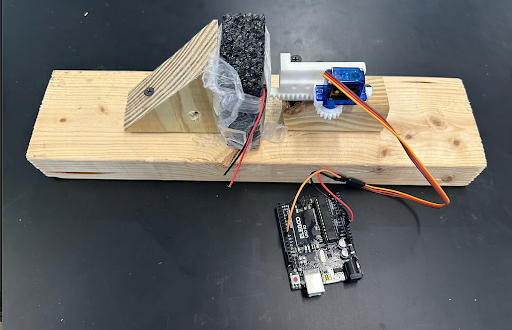

Different pushing and releasing methods were tested for voltage output. Since humans do not apply constant pressure each time, it is an unreliable method to measure. To imitate the same movement a linear actuator utilizing a servo motor operated by an Arduino was used see Figure 6. The servo motor would apply a more consistent push to the piezo. In this study, a custom 3D-printed linear actuator was used to apply mechanical stress to the piezoelectric sensor. The actuator, designed in OnShape, was printed using default settings on a Creality Ender 3 V2 printer with a 0.2mm layer height and 75% infill density to balance strength and flexibility. Once printed, it was paired with a servo motor to simulate consistent tapping force on the sensor, ensuring uniform data collection across trials. Additionally, to fix the position of the servo motor for more consistent results, it was secured to a wooden block and pushed on the piezo that was secured on another wooden block right in front of the linear actuator. Each time the servo motor moved linearly, the piezoelectric sensor would be pushed.

Figure 4:The piezoelectric sensor and “push and release” by hand setup.

Figure 5:The piezoelectric sensor on unbending and bending wrist.

Figure 6:The servo motor and linear actuator setup.

Energy Harvesting and Storage Circuit¶

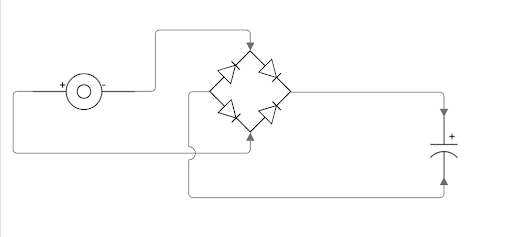

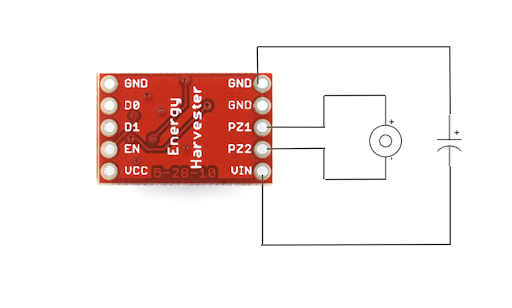

When mechanical stress is applied to piezoelectric sensors, they produce an alternating current (AC) output. However, many biomedical applications require direct current (DC). To convert from AC to DC, a bridge rectifier, which uses diodes to convert AC into DC, and an energy harvesting chip, which efficiently manages and stores harvested energy, Niu et al., 2015 were tested separately, in different circuits, to evaluate which is more efficient in power generation.

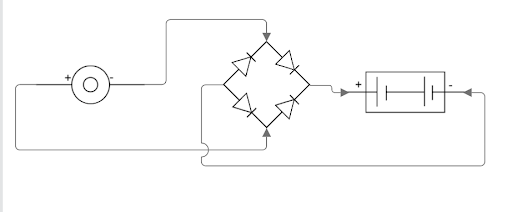

Traditional capacitors, supercapacitors, and rechargeable batteries were tested to store the energy of the piezoelectric sensor for use in a certain device. The traditional capacitors exhibited the fastest charging rates but also lost the energy stored the most quickly. The supercapacitors, although slower to charge,lost charge at a slower rate. Lastly, the rechargeable batteries also required a long charging time, but would store charge for the longest. First, a traditional capacitor was used to charge using both a bridge rectifier see Figure 7 and an energy harvesting chip for comparison see Figure 8. A circuit incorporating both the rectifier and the energy harvesting chip was constructed to charge a traditional capacitor. Charging durations were measured using Vernier software. Capacitors of different sizes (100µF, 220µF, 330µF) were tested to identify the best balance between charge retention and charging speed.

Figure 7:The wiring diagram for the capacitor charging circuit with the rectifier.

Figure 8:The wiring diagram for the energy harvesting chip.

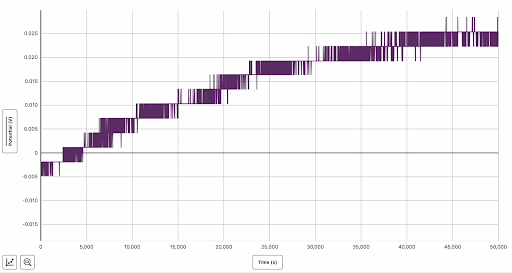

With the use of the bridge rectifier, a supercapacitor was left for 8 hours to charge to gather information on the time it takes to charge it up to explore its feasibility. It was connected the same way as the traditional capacitors. After the supercapacitor, the rechargeable battery was tested. It was connected in the same way as the capacitors see Figure 9. The first rechargeable battery used was an 80 milliamp-hour (mAh) nickel-metal-hydride battery since it charges the quickest from shortened supplied power (Sodana, Inman, Leo, 2003). The nickel-metal-hydride battery contained a chip for voltage regulation. The nickel-metal-hydride battery was charged using a circuit with a rectifier while applying manual mechanical stress.

Figure 9:The wiring diagram for the capacitor charging circuit with a rechargeable battery.

To evaluate their charging rates, the energy harvesting chip and the rectifier were set up to charge various capacitors (100µF, 220µF, 330µF). The slope of each graph was taken to find the average rate of charging for the capacitor in the rectifier and energy-harvesting chip circuit.

When harvesting energy or power, current is also needed Power = Current x Voltage. A multimeter was used to measure the piezoelectric sensor current while charging a capacitor.

Results¶

This section presents the findings from experimentation conducted on piezoelectric sensors and their potential for energy harvesting. The results detail the voltage outputs of different piezoelectric sensors, the impact of mechanical stress application methods, and the efficiency of various energy storage units. The analysis compares the performance of traditional capacitors, supercapacitors, and rechargeable batteries, as well as the efficiency of circuits employing either a bridge rectifier or an energy harvesting chip. These insights are crucial for determining the feasibility of integrating affordable piezoelectric sensors into self-powered biomedical devices.

Choosing the Type of Piezoelectric Sensor¶

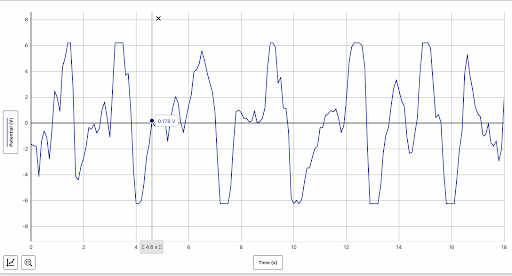

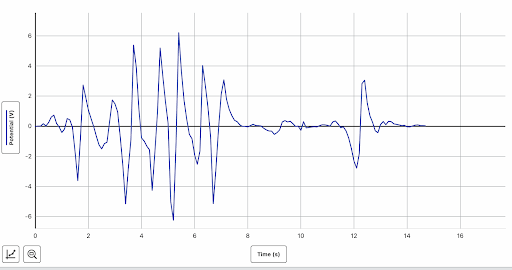

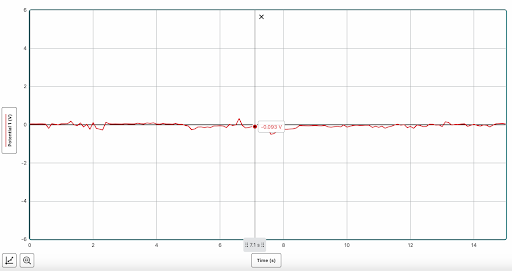

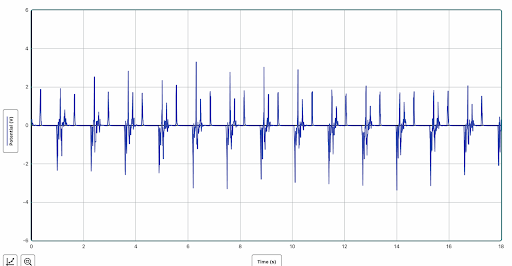

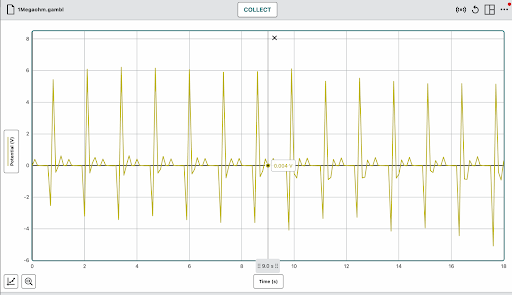

The three piezoelectric sensors were tested by placing them on the wrist while it was in motion. Voltage was measured using a differential voltmeter, and the results can be seen in see Figure 10, see Figure 11, and see Figure 12.

Figure 10:The voltage output of the piezoelectric disc sensor when placed on a moving wrist.

Figure 11:The voltage output of the ribbon sensor when placed on a moving wrist.

Figure 12:The voltage output of the flexible film sensor when placed on a moving wrist.

Among the tested sensors, the disc sensor produced the most consistent voltage output, peaking at 6.14V. The ribbon sensor also reached relatively high voltages at 6.08V but exhibited greater variability. It is important to note that the voltmeter used had a maximum reading of 6V which may have led to inaccuracies in measurements. The film sensor demonstrated the lowest and most inconsistent voltage output, with all readings below 0.5V. Based on these results, the disc sensor was chosen for further experimentation. Additionally, the load resistance was measured to be about 1 Megaohm.

Figure 13:The voltage output of the piezoelectric sensor for load resistor at 100kΩ.

Figure 14:The voltage output of the piezoelectric sensor for load resistor at 220kΩ.

Figure 15:The voltage output of the piezoelectric sensor for load resistor at 1 MΩ.

Optimizing Mechanical Stress Application Results¶

After selecting the disc sensor, different ways to apply mechanical stress were explored. When the disc sensor was taped onto the moving wrist, a very minimal amount of voltage was produced. A more consistent output was observed when the finger manually pressed the sensor against a piece of styrofoam. However, because manual force application was inconsistent, a servo motor was introduced to regulate pressure. When using the servo motor, voltage fluctuations remained within ±0.2V, whereas manual pressing and wrist movements exhibited greater variations, exceeding ±0.3V. This indicates that the servo motor provided the most controlled and reliable method for evaluating the energy harvesting capabilities of the piezoelectric sensor.

Energy Conversion and Storage Results¶

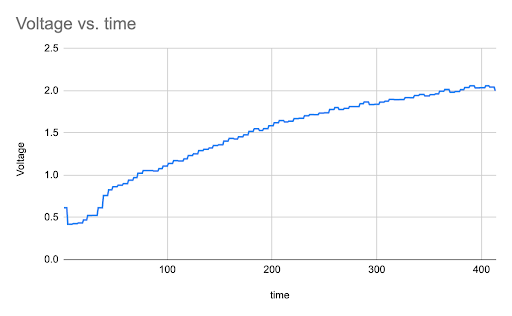

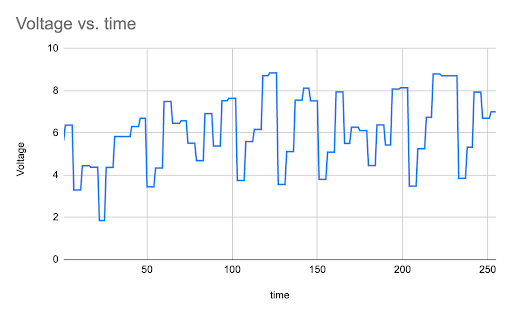

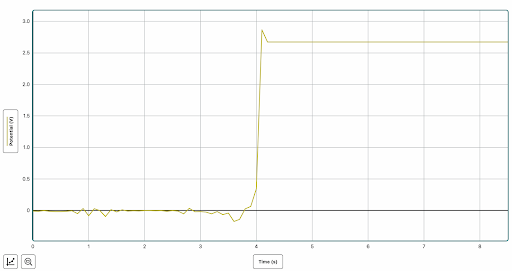

Most biomedical devices require direct current, while piezoelectric sensors generate alternating current Al-Rawi et al., 2023. To bridge this gap, a rectifier and an energy harvesting chip were used to convert AC to DC. The rectifier successfully converted AC to a DC output (see Figure 17). This made all of the voltage outputs positive instead of both positive and negative like in AC. Meanwhile, the energy harvesting chip generated a more linear trajectory of 2.057 volts (see Figure 16), compared to the rectifier’s more fluctuating trajectory.

Figure 16:The voltage versus time graph for the bridge rectifier.

Figure 17:The voltage versus time graph for the energy harvesting chip.

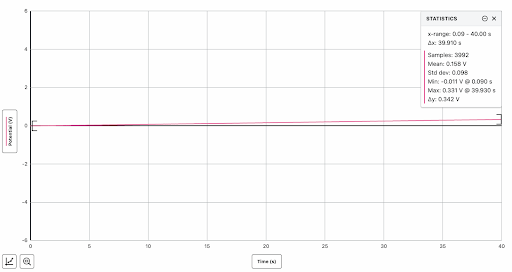

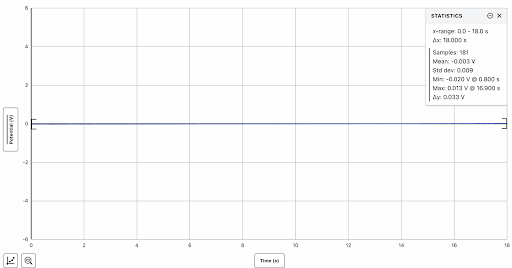

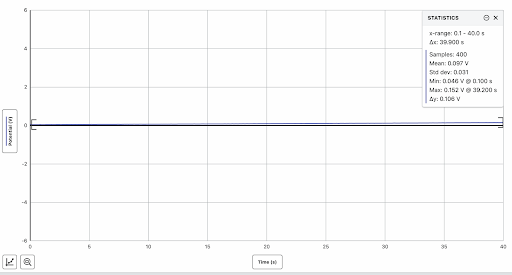

Three storage methods were evaluated: traditional capacitors, supercapacitors, and rechargeable batteries. The 100 µF was charged to 0.331V, the 220 µF capacitor was charged to 0.152 volts, and the 330 µF was charged to 0.013V all within 40 seconds see Figure 18 see Figure 19 see Figure 20. The 20-farad supercapacitor charged 0.027V volts over 50,000 seconds see Figure 21.

Figure 18:The 100 µF capacitor being charged for 40 seconds by the piezoelectric sensor with rectifier as AC to DC converter (voltage vs. time).

Figure 19:The 220 µF capacitor being charged for 40 seconds by the piezoelectric sensor with rectifier as AC to DC converter (voltage vs. time).

Figure 20:The 330 µF capacitor being charged for 40 seconds by the piezoelectric sensor with rectifier as AC to DC converter (voltage vs time)

Figure 21:The supercapacitor being charged by the piezoelectric sensor with rectifier as AC to DC converter for 50,000 seconds (voltage vs. time).

Rechargeable battery testing revealed decreasing efficiency over multiple trials. Initially, the battery held a charge for two minutes, but after repeated use, its charge retention dropped to just 10 seconds. One servo push was sufficient to charge it to approximately 2.1V see Figure 22. Further research is needed to optimize battery performance for sustained energy storage.

Figure 22:The rechargeable battery being charged by the piezoelectric sensor with rectifier as AC to DC converter from a single servo push (voltage vs. time).

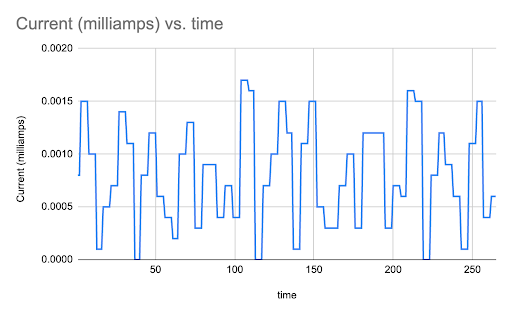

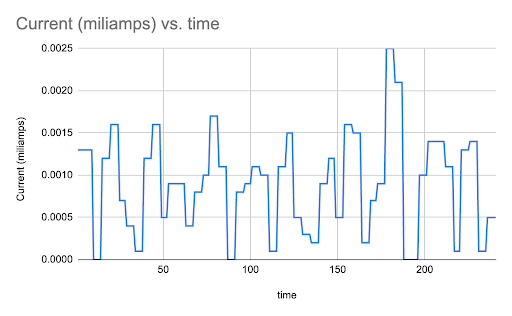

Current Measurements and Power Output¶

Determining power output is essential for assessing whether a piezoelectric sensor can sufficiently supply energy for biomedical devices. Power (P=IV) whether such sensors can support continuous operation or are more suited for intermittent energy bursts. Higher power output from manually pressing the sensor suggests the potential for applications needing quick energy bursts, like emergency-activated biosensors. On the other hand, lower but more consistent power output from a servo motor may be better suited for devices requiring steady energy, such as continuous heart rate or glucose monitors. Understanding these power dynamics helps align sensor performance with the specific energy demands of biomedical applications, enabling the development of more reliable, self-powered medical devices that reduce reliance on traditional batteries.

The DC voltage of the piezoelectric sensor, after conversion to AC, was multiplied by the measured current from the rectifier and energy harvesting chip. The average current from the energy harvesting chip was measured at about 0.0124A see Figure 22 and the average current from the rectifier was measured at about 0.0162A before integration into a storage circuit see Figure 23. These measurements show the feasibility and give insights into building an energy harvesting circuit in the future.

Figure 23:The current versus time graphs for the energy harvesting chip.

Figure 24:The current versus time graph for the rectifier.

To effectively integrate piezoelectric sensors into a self-powered biomedical device, a complete system—including the disc sensor, rectifier, or energy harvesting chip, and a storage device—must be assembled alongside the biosensor. The sensor needs to be placed on a body part that experiences frequent pushing and releasing forces, such as the palm (via squeezing) or the sole of the foot (via walking). The schematic of a potential diagram to power a device with piezoelectric sensors can be seen in see Figure 25.

Figure 25:Extension of piezoelectric energy harvesting circuit for biomedical applications.

Testing the circuit under extended operational conditions will help determine whether a biomedical device can remain functional for extended periods of time.

Overall, the results indicate that the disc sensor, when paired with a rectifier and a traditional capacitor, provided the most effective combination for energy harvesting and storage. This configuration holds significant promise for integrating affordable piezoelectric technology into self-powered biomedical devices, paving the way for more sustainable and reliable energy solutions.

Discussion¶

The findings from this study highlight the promising potential of using affordable piezoelectric sensors for energy harvesting in biomedical devices. The disc sensor, chosen for its consistent and relatively high voltage output, proved to be the most effective option for further development. Additionally, the use of a servo motor for mechanical stress application demonstrated that automated systems provide more reliable and consistent data compared to manual methods, where human error can affect the pressure consistency and, consequently, alter voltage output.

The comparison between the energy storage methods—including traditional capacitors, supercapacitors, and rechargeable batteries—highlighted important compromises. While the traditional capacitors charged more quickly, they also discharged rapidly. Among them, the 220 µF capacitor emerged as the most balanced option due to its faster charging rate and moderate energy retention. On the other hand, supercapacitors and rechargeable batteries, though slower to charge, demonstrated superior long-term energy retention, making them more suitable for applications that require sustained power over longer periods. These findings suggest that an integrated storage solution combining capacitors and batteries could potentially energy utilization biomedical applications—allowing capacitors to handle quick bursts of power and while batteries store power for extended use.The batteries would allow for effective energy storage and the capacitors would help charge them without much stress from humans.

Despite these promising results, the study faced several limitations. The low output voltage and current of the disc sensor posed challenges for powering devices with higher energy demands. Additionally, while the controlled testing environment helped minimize experimental variability, it did not fully replicate real-life conditions. In practical applications, the unpredictable movements of the human body may impact energy generation efficiency. Future studies should explore sensor performance in real-world conditions, such as attachment to different body parts during various physical activities, to better understand its practical viability.

To further improve energy harvesting efficiency, future research should focus on optimizing mechanical-to-electrical energy conversion by refining the mechanical setup to maximize output. Additionally integrating multiple piezoelectric sensors in parallel or series could help increase the voltage and current output. Improving energy storage efficiency is another key area, as hybrid solutions that combine the quick charging abilities of capacitors with the steady output of rechargeable batteries could provide a more reliable and sustained power source. Finally, investigating alternative materials for the piezoelectric sensors that may offer higher voltage output while still remaining cost-effective would further improve the feasibility of this technology for self-powered medical devices..

Overall, this study supports the idea that affordable piezoelectric technology holds significant potential for powering biomedical devices, offering a step toward more sustainable, battery-independent solutions Janes, 2025. These findings pave the way for future advancements that could improve both the energy harvesting capability and storage efficiency of these systems, therefore reducing dependence on traditional batteries. Such developments could lead to a new generation of wearables and implants, improving patient care and reducing the need for battery replacements, thus mitigating environmental impact and improving user convenience.

Conclusion¶

In conclusion, this study demonstrates the feasibility of utilizing affordable piezoelectric sensors for energy harvesting in biomedical devices, presenting a potential alternative to traditional batteries. The disc sensor exhibited the highest voltage output and consistent performance, making it the optimal choice for further development. Additionally, the implementation of a rectifier for AC to DC conversion, coupled with traditional capacitors for energy storage, provided the most efficient charging cycle.

The findings of this study underscore the importance of power output calculations, as they directly influence the effectiveness of charging methods and the overall functionality of self-powered biosensors. The ability to harvest energy from human movement presents exciting opportunities for the development of sustainable biomedical applications.

Future research should focus on optimizing the integration of these systems into practical medical devices, ensuring seamless functionality and efficiency. Additionally, exploring various sensor configurations could enhance energy output and adaptability, making the technology more effective for various applications. Conducting real-world testing is also essential to evaluate the reliability and performance of piezoelectric energy harvesting in diverse healthcare settings. By addressing these areas, this technology could become a viable solution for self-sustaining medical devices, reducing dependence on traditional batteries and improving long-term patient care.

Copyright © 2024 Sriram. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, which enables reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the creator.

- AC

- alternating current

- DC

- direct current

- mAh

- milliamp-hour

- Al-Rawi, O. F., Bicer, Y., & Al-Ghamdi, S. G. (2023). Sustainable solutions for healthcare facilities: examining the viability of solar energy systems. Frontiers in Energy Research, 11. 10.3389/fenrg.2023.1220293

- Niu, S., Wang, X., Yi, F., Zhou, Y. S., & Wang, Z. L. (2015). A universal self-charging system driven by random biomechanical energy for sustainable operation of mobile electronics. Nature Communications, 6(1), 8975. 10.1038/ncomms9975

- Janes, H. (n.d.). Piezoelectric Energy Harvesting within Wearable Devices. Retrieved April 15, 2025, from https://blog.piezo.com/piezoelectric-energy-harvesting-within-wearable-devices