Evaluating the Effect of an Externally Applied Electric Field on Fluorescing Alpha-Synuclein Aggregates in NL5901 Parkinson's Disease Model of Caenorhabditis elegans

Abstract¶

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is characterized by the progressive aggregation of alpha-synuclein, a protein that forms toxic fibrils, leading to motor dysfunction and neuronal degeneration. In this study, I investigated the effects of exposure to various external electric fields on alpha-synuclein aggregation and neuromuscular function in Caenorhabditis elegans, a model organism frequently used to study neurodegenerative diseases. Two independent trials were conducted, with worms exposed to the electric field or maintained as unexposed controls. Neuromuscular function was assessed by measuring thrashing frequency, a proxy for motor coordination, while alpha-synuclein aggregation was quantified using fluorescence microscopy in the C. elegans strain NL5901, which expresses human alpha-synuclein fused to yellow fluorescent protein (YFP). Results revealed a significant increase in thrashing frequency in worms exposed to the electric field, suggesting improved neuromuscular health. Additionally, exposure to the electric field led to a marked reduction in alpha-synuclein aggregate size, with a 38.7% decrease in aggregate area compared to controls. A strong negative correlation (r = -0.92) was observed between alpha-synuclein aggregation and thrashing frequency, supporting the hypothesis that disrupting alpha-synuclein aggregation enhances motor function. These findings indicate that electric field exposure may represent a promising therapeutic strategy for mitigating the effects of alpha-synuclein aggregation in PD. Future research will focus on running more trials, and with replication of results, elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying these effects and exploring the potential of this approach in higher organisms.

Introduction¶

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder affecting more than 10 million patients worldwide Poewe et al., 2017. PD is a neurological movement disorder that is characterized by impaired balance, bradykinesia, rigidity, and the presence of resting tremors. In addition to deficits in movement, PD patients can also exhibit non-motor symptoms including depression, apathy, anxiety, dementia, and others. The prevalence of PD is 0.3% among all ages but increases to more than 3% in individuals over 80 years of age Pringsheim et al., 2014.

PD exhibits progressive degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the brain in the substantia nigra, although many other brain regions are also affected. Neuronal loss within the substantia nigra decreases dopamine signaling to the striatum thereby contributing to the motor symptoms of PD. At the cellular level, the disease is characterized by intracellular aggregation of a protein called 𝛼-synuclein into Lewy bodies observed in the brains of patients with PD Spillantini et al., 1998. There are currently no neuroprotective treatments available for PD and the pathogenesis of the disease is incompletely understood.

Materials and Methods¶

About the model organism¶

The nematode C. elegans is a microscopic roundworm that grows 1-2 mm long. After hatching, these animals develop to adulthood in just 2 days under laboratory conditions at 20°C. Once these worms reach adulthood, their average lifespan is 2-3 weeks, making them useful for aging studies. C. elegans exists primarily as a self-fertilizing hermaphrodite, in which all of the progeny are genetically identical. Males are a small fraction of the population (<0.1%) but their numbers can be greatly increased in the laboratory to facilitate genetic crosses. This animal is genetically tractable with robust tools for spatiotemporal control of gene expression and a highly annotated genome. Because C. elegans are transparent, fluorescent proteins can be readily visualized in a live worm to measure levels and location of gene products of interest. These animals have been utilized to address various cellular and genetic questions Corsi et al., 2015 and to gain insight into neurodegenerative disease Dexter et al., 2012.

C.elegans have a well-defined, invariant nervous system with exactly 302 neurons in each hermaphrodite out of a total of 959 cells in the organism. Unlike any other organism, the connections of all 302 neurons in C.elegans have been mapped using electron micrographs thereby providing the most complete nervous system connectome of any organism The Royal Society, 1986. Importantly, these neurons encode complex behaviors which, in several cases, have been described at the level of a single neuron Xue et al., 1992.

By utilizing the nematode model for Parkinson’s Disease that over-express the human disease-causing 𝛼-synuclein fused to a fluorescent reporter in the body wall muscles, strain NL5901 Ham et al., 2008, it is possible to directly monitor 𝛼-synuclein aggregation throughout life. This nematode strain mimics the 𝛼-synuclein aggregation found in Lewy bodies and idiopathic PD Spillantini et al., 1997. The open-source ImageJ software was employed to quantify changes in the aggregation of the 𝛼-synuclein throughout the lifespan of the nematode in parallel to a behavioral assay as a robust and representative readout of the lifespan of the nematode in parallel to neuromuscular health.

Application of Electric Field¶

Parkinson’s Disease is a category of neurodegenerative disorders that currently lack comprehensive and definitive treatment strategies. The etiology of PD can be attributed to the presence and aggregation of a protein known as 𝛼-synuclein. Researchers have observed that the application of an external electrostatic field holds the potential to induce the separation of the fibrous structures into peptides. To comprehend this phenomenon, their investigation involved simulations conducted on the 𝛼-synuclein peptides through the application of Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation techniques revealed that in the presence of an external electric field, the monomer and oligomeric forms of a 𝛼-synuclein are experienced significant conformational changes which could prevent them from further aggregation. When 𝛼-synuclein predominantly exists in its monomeric or dimeric form, applying even a lower electric field could effectively disrupt the initial aggregation process. Inhibition of 𝛼-synuclein fibril formation at early stages might serve as a viable solution to combat PD by halting the formation of more stable and pathogenic 𝛼-synuclein fibrils Razzokov et al., 2023.

Preparation and Maintenance of C.elegans¶

Caenorhabditis elegans strain NL5901, which overexpresses the human disease-associated 𝛼-synuclein fused to a yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) in the body wall muscles, was used for all experiments. This strain was obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC) and maintained under standard laboratory conditions on nematode growth medium (NGM) agar plates seeded with Escherichia coli OP50 as the food source. Worm cultures were maintained at 20°C to ensure optimal growth and development.

Design and Fabrication of the Electric Field Apparatus¶

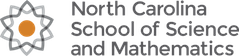

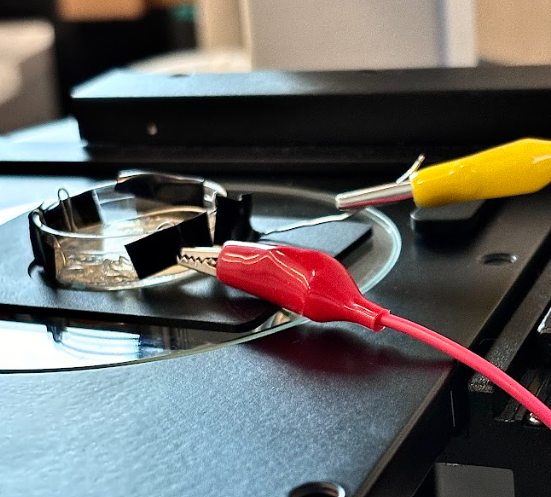

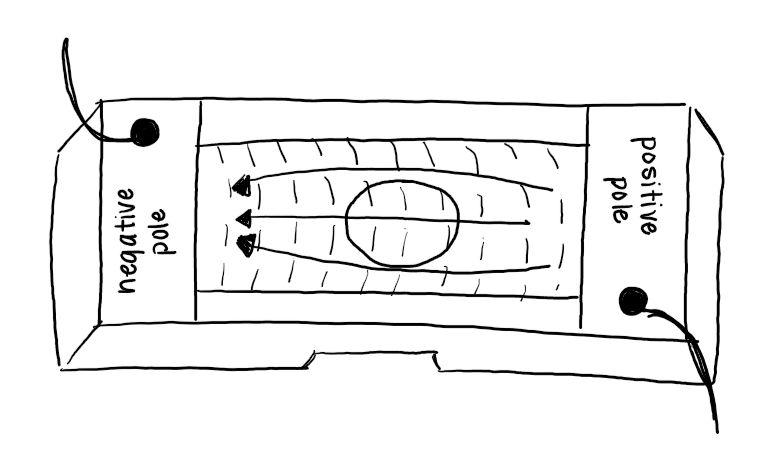

To generate a uniform electric field across the NGM agar, a gel electrophoresis power source (BIO-RAD PowerPac Basic) was used to supply a constant voltage of 40V see Figure 3. Custom copper plate electrodes were embedded into opposite sides of a mini Petri dish containing NGM agar see Figure 1. Nematode growth medium agar was purchased pre-prepared from Carolina Biological. The agar was poured into standard Petri dishes with dimensions of 100 mm x 15 mm to a uniform depth of about 3 mm. Pre-sterilized copper plates were embedded on opposite sides of each dish during the pouring process, ensuring even contact with the agar surface. The copper plates were molded to fit snugly within the Petri dish, ensuring consistent contact with the agar surface while minimizing air gaps. The plates were thoroughly cleaned with ethanol and deionized water before use to eliminate potential contaminants and ensure reliable conductivity. The plates were positioned to maintain a fixed distance of 10mm between the electrodes. The agar was allowed to solidify at room temperature before use.

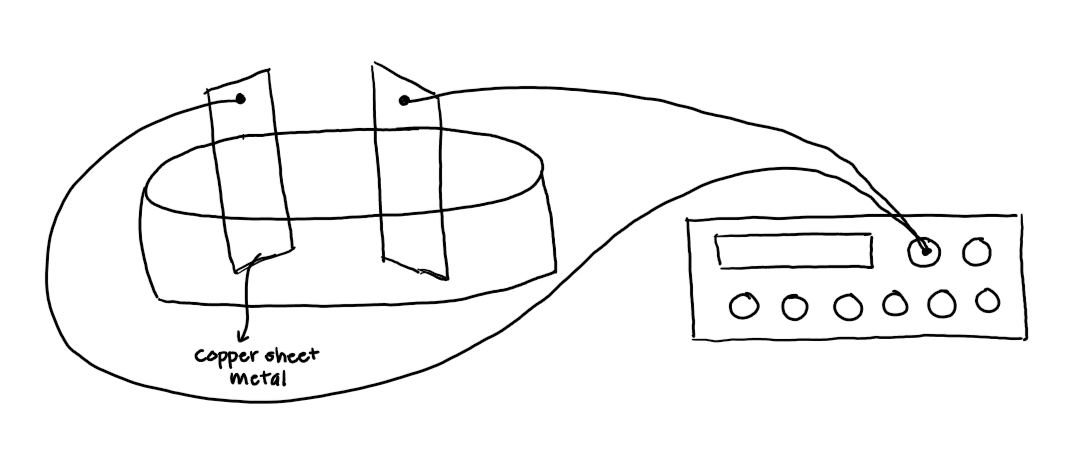

Electrical connections were established using insulated alligator clips, which were securely fastened to the copper electrodes see Figure 2. These clips were connected to the output terminals of the power source, completing the circuit. The system was tested before each experiment to confirm the generation of a stable electric field across the agar. Voltage consistency was monitored throughout the experiment using a setting on the gel electrophoresis power source.

Figure 1:Sketch of the intended electric field apparatus before being built

Figure 2:Electric Field Apparatus setup using alligator clips to close the circuit

Figure 3:Electric Field Apparatus setup using Biorad power source and custom banana clips to ensure proper connection

Figure 4:Sketch of direction in which electric field will act upon worms

Calibration and Monitoring of the Electric Field¶

The electric field was calculated based on the applied voltage and the distance between the copper electrodes. The power source was set to deliver a constant voltage of 40 V, and the field strength was determined by dividing the voltage by the separation between the electrodes (in cm). The current through the gel was measured periodically using the multimeter and was found to fluctuate between 300 µA and 311 µA, likely due to the slight variations in the gel composition and electrode contact.

Exposure of C. elegans to the Electric Field¶

C. elegans were transferred to the prepared NGM plates with the embedded electrodes. A maximum of three worms were placed on each plate using a platinum wire worm picker sterilized in ethanol. To minimize dehydration and stress, the agar plates were sealed with Parafilm and maintained at room temperature during the exposure period. The plates were subjected to the electric field for varying durations to assess both short and long-term effects on 𝛼-synuclein aggregation and neuromuscular health. Control groups were maintained under identical conditions without electric field exposure.

Quantification of 𝛼-synuclein Aggregation¶

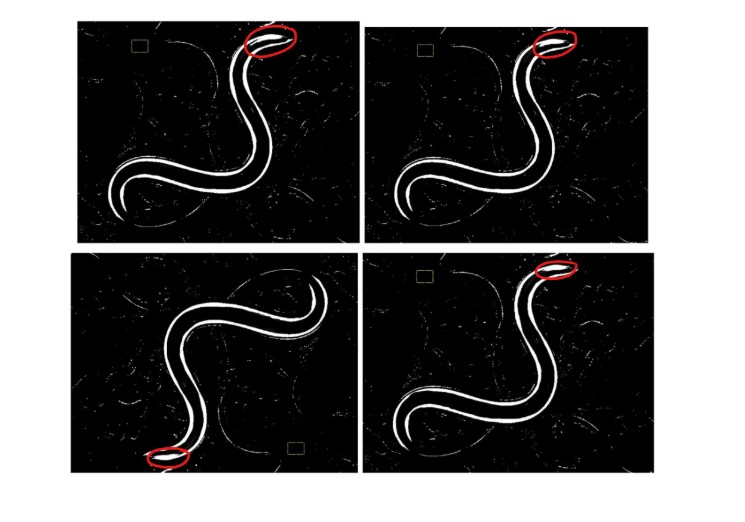

Fluorescent imaging of C. elegans was conducted using a confocal microscope (Accuscope EXI-310) to visualize and quantify 𝛼-synuclein-YFP aggregates. Images were acquired using identical exposure settings for all samples to allow for direct comparisons.

Aggregate quantification was performed using the ImageJ software. Aggregates were identified and segmented based on intensity thresholds, and the total number of aggregates per worm was recorded. Data from two independent experiments, each including three worms per condition, were analyzed to assess the effects of the electric field.

Behavioral Assays¶

To evaluate neuromuscular health, thrashing assays were performed. Individual worms were placed in 50µL of M9 buffer on a glass slide, and the number of body bends completed in 30 seconds was recorded under a microscope (Accuscope). Body bends were defined as a complete movement of the head from one side of the midline to the other. Thrashing assays were conducted immediately after electric field exposure and at regular intervals.

Validation of Worm Health During Exposure¶

Worm health was assessed by observing locomotion and morphology during the exposure period. No abnormalities or stress responses were detected in the experimental worms, allowing all three to be included in subsequent analyses.

Results¶

Neuromuscular Health Assessment Using Thrashing Frequency¶

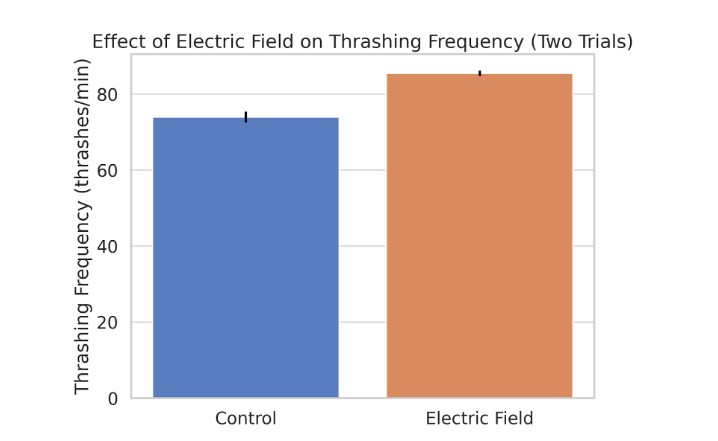

The thrashing frequency of C. elegans was utilized as a robust proxy for neuromuscular health, allowing us to investigate the physiological impact of a uniform electric field (40V) on the nematode’s motor function. Two independent trials were conducted to ensure reproducibility, with worms exposed to either electric field conditions or maintained as unexposed controls.

The average thrashing frequency across both trials revealed a marked improvement in the neuromuscular performance of the worms exposed to the electric field see Figure 5. Worms in the experimental group exhibited a mean thrashing frequency of 85.5 ± 1.4 thrashes per minute, in contrast to 74.0 ± 2.1 thrashes per minute for the control group. Statistical analysis using a paired, two-tailed t-test demonstrated the significance of this increase (p=0.015), supporting the hypothesis that exposure to the electric field positively influences motor function.

Table 1:Thrashing Frequency of C. elegans

| Experiment Group | Thrases/Minute (Trial 1) | Thrases/Minute (Trial 2) | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 73 | 75 | 74.0 ± 2.1 |

| Electric Field | 86 | 85 | 85.5 ± 1.4 |

Figure 5:Graphical Representation of the Effect of the Electric Field on Thrashing Frequency

Further inspection of individual data points is depicted in Figure 5, which displays the thrashing frequency of individual worms from both trials. This figure highlights the consistency in the neuromuscular enhancement observed across trials. Both control and experimental groups exhibited minimal variability, as reflected by the relatively small standard deviations.

Neuromuscular Health Assessment Using Velocity¶

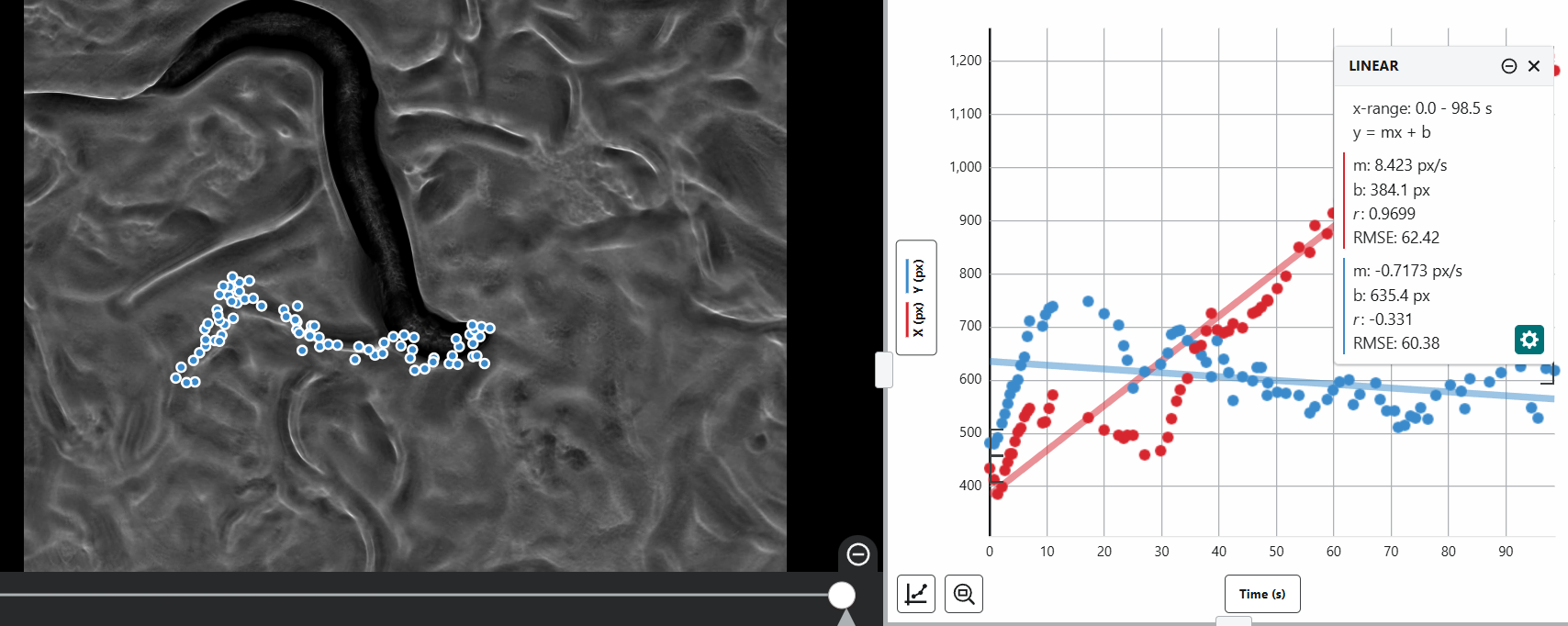

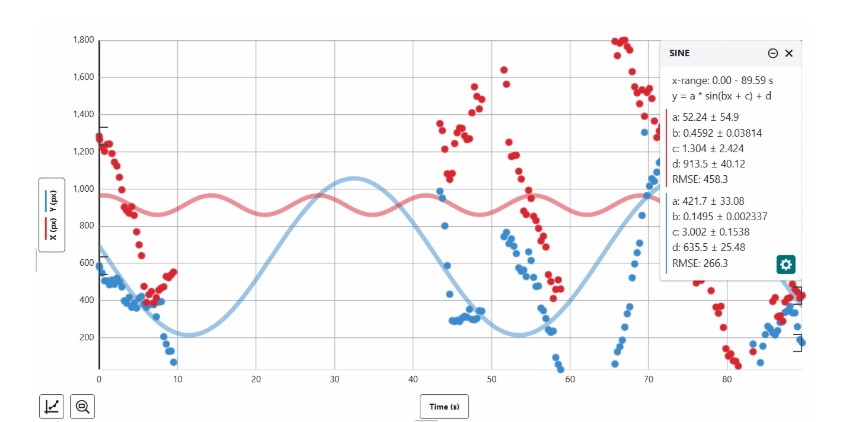

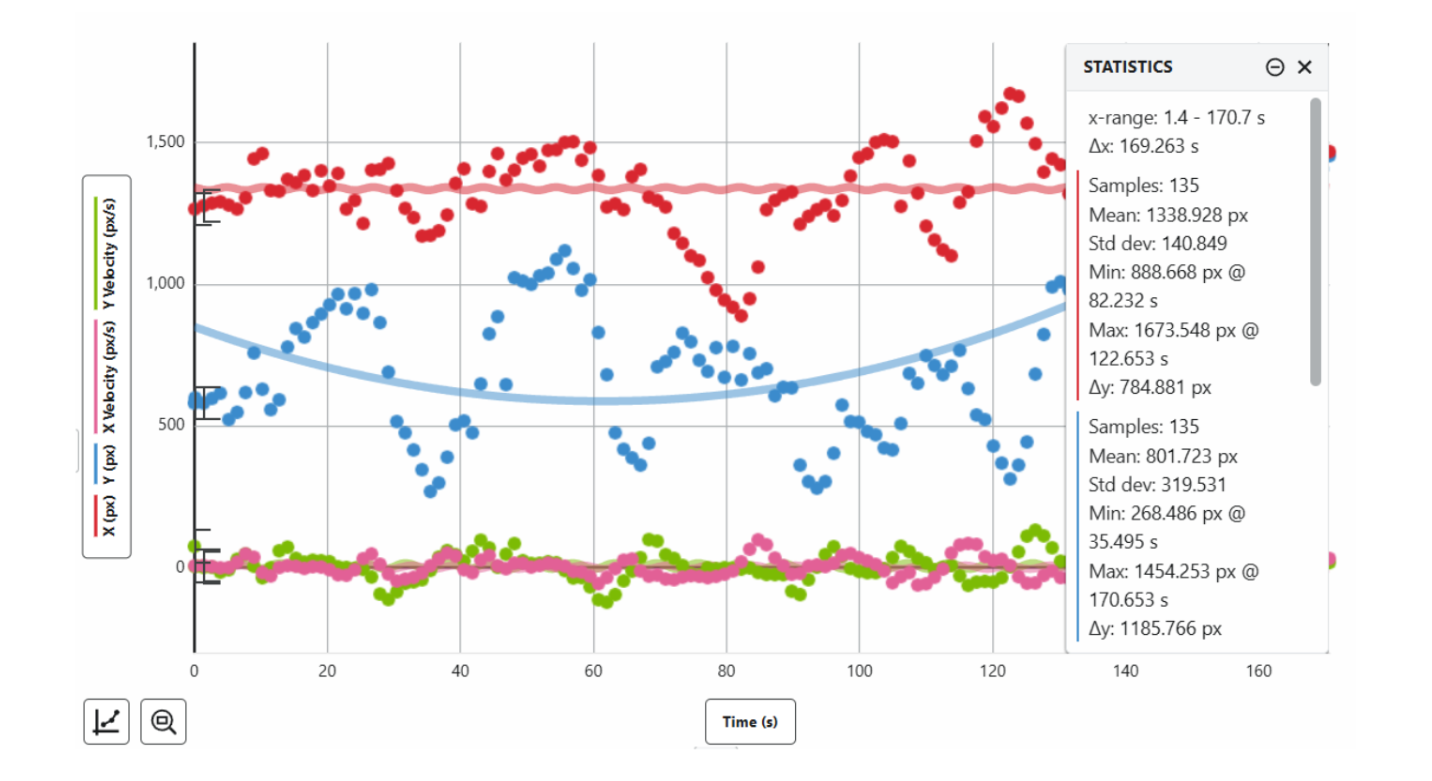

Vernier Video Analysis software was utilized to quantify the movement speed of C. elegans. Videos of the worms were recorded, and their head positions were marked every five video frames to track their motion see Figure 6. By analyzing the positional changes over time, the average speed of each worm was calculated in pixels per second (px/s). This method ensured precise and consistent tracking across all experimental conditions.

Figure 6:Mapping the movement of N2 worms using Vernier Video Analysis

The results demonstrated distinct differences in movement speed across the experimental groups. The control worm with no protein aggregation and no electric field exposure exhibited an average speed of 13.22 px/s. As expected, the worm with PD and no electric field exposure displayed a significantly reduced speed of 8.423 px/s, representing a 36.3% decrease compared to the healthy control, which aligns with the impaired neuromuscular functionality associated with PD see Figure 7.

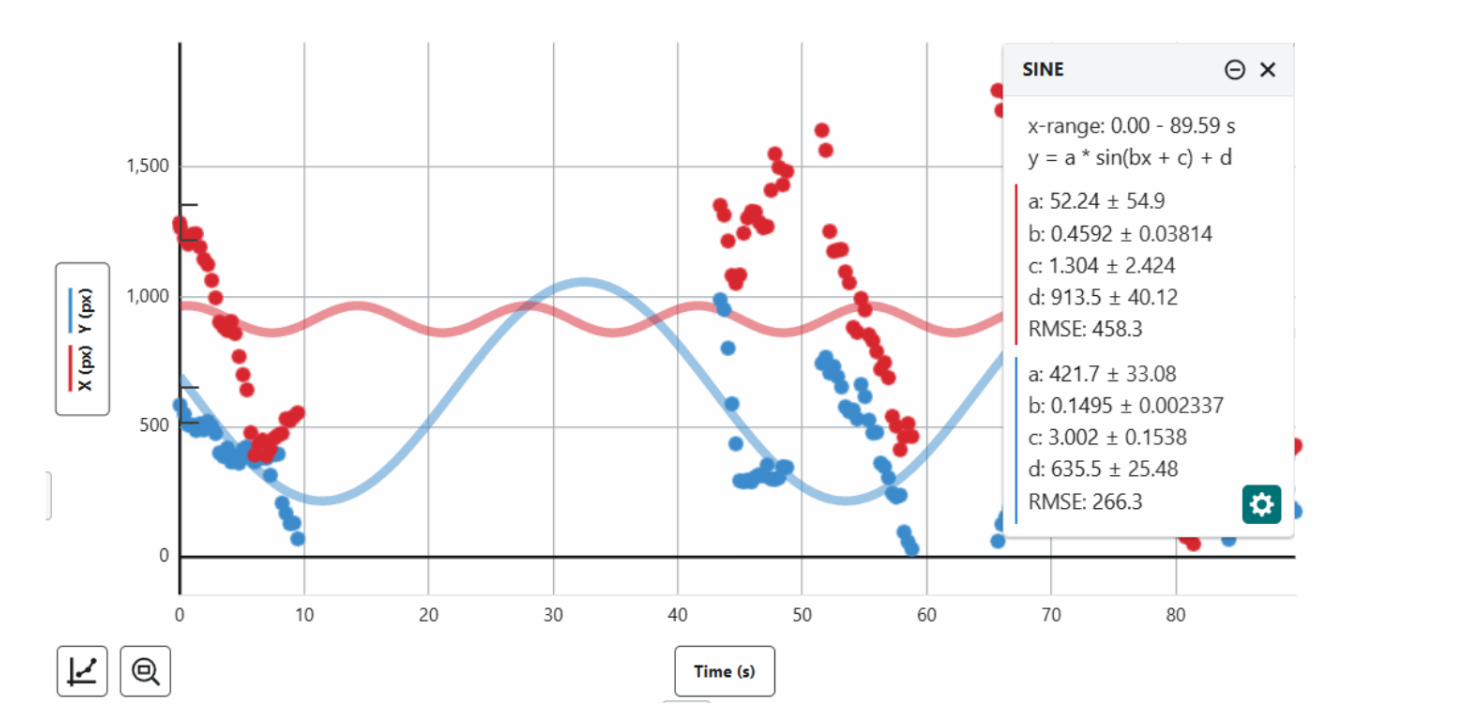

The worm with PD under the influence of the electric field showed a marked improvement, achieving an average speed of 126.358 px/s. This represents a staggering increase compared to the PD worm without electric field exposure and an increase compared to the healthy control. Even after the electric field was turned off, the worm with PD maintained a higher-than-expected average speed of 114.896 px/s, higher than the PD worm without the electric field and higher than the healthy control (see Figure 8 and Figure 9). This suggests a sustained positive effect of the electric field on neuromuscular health and functionality.

Figure 7:Mapping the movement of NL5901 worms without exposure to electric field using Vernier Video Analysis

Figure 8:Mapping the movement of NL5901 worms with exposure to electric field using Vernier Video Analysis

Figure 9:Mapping the movement of NL5901 worms after exposure to electric field using Vernier Video Analysis

Table 2:Velocity of C. elegans

| Model | Exposure to Field (Yes/No) | Average velocity (px/s) |

|---|---|---|

| N2 | No | 13.22 |

| NL5901 | No | 8.423 |

| NL5901 | Yes | 126.358 |

| NL5901 | Yes | 114.896 |

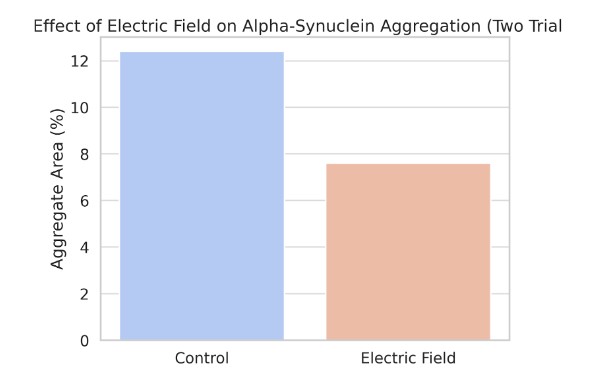

𝛼-Synuclein Aggregation Quantification¶

To assess the biochemical impact of electric field exposure, the aggregation of alpha-synuclein, a hallmark of Parkinson’s disease pathology, was quantified using C. elegans strain NL5901. This strain overexpresses human alpha-synuclein fused to a fluorescent YFP reported, enabling direct visualization of aggregation in the body wall muscles.

Using ImageJ software, fluorescence images of the worms were converted to grayscale to facilitate the segmentation of alpha-synuclein aggregates. Quantification revealed a statistically significant reduction in the aggregate area following electric field exposure. Control worms exhibited an average aggregate area of 12.4 ± 0.6%, while worms exposed to the electric field displayed a reduced aggregate area of 7.6 ± 0.3%, corresponding to a 38.7% reduction in aggregate size. This reduction indicates that the electric field may disrupt the aggregation of alpha-synuclein fibrils or prevent their further formation.

Table 3:Alpha-Synuclein Aggregate Area in C. elegans

| Experiment Group | Aggregate Area (%) (Trial 1) | Aggregate Area (%) (Trial 2) | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 12.4 ± 0.5 | 12.5 ± 0.6 | 12.4 ± 0.6 |

| Electric Field | 7.5 ± 0.4 | 7.7 ± 0.3 | 7.6 ± 0.3 |

The data is summarized in Figure 10, which shows the average aggregate area across two independent trials. To provide additional granularity, Figure 11 displays the distribution of fluorescent intensity within the aggregates, highlighting the reduction in aggregate density under electric-field conditions.

Figure 10:Aggregate Area (Two Trials)

Figure 11:Degradation of alpha-synuclein protein (in white) through electric field exposure visualized through ImageJ software

Correlation Between Neuromuscular Health and 𝛼-Synuclein Aggregation¶

To investigate the relationship between neuromuscular health and alpha-synuclein aggregation, the thrashing frequency and aggregate area were plotted as paired data points from individual worms in both trials. A clear inverse correlation was observed, as shown in Figure 12. Worms with smaller aggregate areas consistently exhibited higher thrashing frequencies.

Statistical analysis revealed a Pearson correlation coefficient of -0.92, indicating a strong negative correlation (p<0.001). This finding underscores the hypothesis that 𝛼-synuclein aggregation adversely impacts neuromuscular health and that disrupting this aggregation can alleviate motor deficits. The electric field appears to mitigate aggregation, thereby improving neuromuscular performance.

-01219ab79f220c632d5338aa37873cbf.png)

Figure 12:Correlation between Aggregation and Thrashing

Behavioral Stability and Morphological Observations¶

Throughout the experimental procedures, the health and integrity of the worms were closely monitored to ensure that the electric field exposure did not induce undue stress or morphological abnormalities. Behavioral assays confirmed normal locomotion and body morphology during and after exposure. Control and experimental groups exhibited similar baseline behaviors before the application of the electric field, affirming that any observed improvements in thrashing frequency were due to the experimental conditions rather than random variability.

Discussion, Conclusions, Future Work¶

This study provides insight into the potential therapeutic effects of an external electric field on the aggregation of alpha-synuclein and its subsequent impact on neuromuscular function in Caenorhabditis elegans as a model for Parkinson’s disease (PD). Our findings support the hypothesis that exposure to a 40C electric field can disrupt alpha-synuclein aggregation, leading to improvements in motor function as assessed by the thrashing frequency assay. These results suggest that the manipulation of external electric fields could represent a promising direction in the development of PD therapies, particularly in mitigating the detrimental effects of alpha-synuclein aggregation, a hallmark of the disease.

Impact of Electric Field on Neuromuscular Function¶

The thrashing assay was employed as a surrogate measure of neuromuscular health, as it reliably reflects motor coordination and muscle function in C. elegans. This assay, quantifying the number of body bends or thrashes per minute, is an established method for assessing the locomotor capabilities of the organism, particularly in models of neurodegenerative diseases like PD Lavorato et al., 2021. In our study, worms exposed to a 40V electric field exhibited a significant increase in thrashing frequency when compared to the control group, demonstrating an enhancement in neuromuscular health.

The increase in thrashing frequency could reflect several underlying biological mechanisms. One possible explanation is that the electric field directly modulated neuromuscular activity, possibly by affecting ion channel activity or synaptic transmission. Recent studies have suggested that electric fields can influence cellular and neuronal activity by altering membrane potentials or ion fluxes, which could in turn impact motor function Aguilar et al., 2021. The observed improvements in thrashing behavior could also result from a reduction in alpha-synuclein aggregation, as a decrease in aggregation has been shown to restore normal motor function in PD models Minakaki et al., 2020.

Statistical analysis confirmed the reliability of these findings, with a paired, two-tailed t-test yielding a significant result (p=0.015). This suggests that the observed enhancement in thrashing frequency was unlikely to be due to random variability. The consistency across two independent trials, as reflected in both the mean values and low standard deviation in Table 1, further supports the robustness of the electric field’s impact on neuromuscular health.

𝛼-Synuclein Aggregation and its Disruption¶

Alpha-synuclein aggregation is one of the central pathological features of PD, leading to the formation of Lewy bodies that impair neuronal function Spillantini et al., 1998. In this study, the C.elegans strain NL5901 was employed, which expresses human alpha-synuclein fused to a yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) in the body wall muscles. This strain provides an excellent model to visualize and quantify alpha-synuclein aggregation in vivo, as fluorescent protein allows for direct imaging of aggregate formation over time.

Our results demonstrated that exposure to the electric field significantly reduced the aggregate area of alpha-synuclein, with a reduction of approximately 38.7% compared to control worms as summarized in Table 2. This reduction in aggregation suggests that the electric field has a disruptive effect on the formation of alpha-synuclein fibrils. Previous studies have suggested that physical or electrical stimuli can influence protein confirmation, potentially disrupting amyloid fibril formation Vargas-Rosales et al., 2023. The precise mechanism by which the electric field induces this effect remains speculative, but several hypotheses warrant consideration. The electric field may alter the conformational stability of alpha-synuclein monomers or oligomers, preventing their transition into the fibrillar forms that constitute aggregates. Alternatively, the electric field may induce local heating, which has been shown to influence protein aggregation dynamics Wu et al., 2022.

The statistical significance of these findings was confirmed through quantitative analysis of aggregate area using ImageJ software. As shown in Table 3, worms exposed to the electric field exhibited a significantly smaller aggregate area compared to control worms, supporting the hypothesis that the electric field disrupts alpha-synuclein aggregation.

Correlation Between 𝛼-Synuclein Aggregation and Neuromuscular Health¶

A key aim of this study was to examine the relationship between alpha-synuclein aggregation and neuromuscular health. This analysis revealed a strong negative correlation between alpha-synuclein aggregate size and thrashing frequency, with a Pearson correlation coefficient of -0.92 (p < 0.001), as depicted in Figure 12. This finding supports the hypothesis that larger alpha-synuclein aggregates impede motor function, a well-established observation in PD models Srinivasan et al., 2021. The significant inverse correlation between these two variables implies that reducing the size of alpha-synuclein aggregates through electric field exposure may alleviate motor deficits, offering a mechanistic explanation for the observed improvement in thrashing behavior.

This result also corroborates previous studies demonstrating the detrimental effects of alpha-synuclein aggregation on motor function. In particular, reductions in aggregation have been linked to the restoration of normal motor behavior in both C. elegans and mammalian models of PD Vidović & Rikalovic, 2022. The electric field-induced reduction in aggregation may therefore represent a novel therapeutic avenue for treating or preventing the progression of PD, particularly in the early stages when alpha-synuclein aggregation is still in its nascent form.

Behavioral and Morphological Observations¶

To ensure that the observed improvements in thrashing frequency were not due to factors unrelated to the electric field exposure, the worms were closely monitored for any signs of behavioral instability or morphological abnormalities. Throughout the experiments, both control and experimental groups exhibited normal locomotion and body morphology. No stress responses such as changes in body posture, lethargy, or altered movement patterns, were observed in any of the groups, indicating that the electric field exposure did not induce undue harm to the worms. This is crucial, as it confirms that the observed improvements in neuromuscular health were indeed a direct result of electric field exposure, rather than compensatory effects or recovery from an initial stressor.

Conclusion¶

In conclusion, this study provides compelling evidence that exposure to an external electric field can significantly reduce alpha-synuclein aggregation and improve neuromuscular function in C. elegans, a well-established model for Parkinson’s disease. Our findings suggest that the electric field may be a viable strategy for disrupting alpha-synuclein aggregation, a key pathological feature of PD and that this disruption is associated with improvements in motor function. These results provide an exciting potential for future PD therapies that target the aggregation of pathogenic proteins, particularly in the early stages of disease progression.

The observed reduction in alpha-synuclein aggregation, coupled with the enhancement in thrashing frequency, underscores the therapeutic potential of physical and electrical interventions in neurodegenerative diseases. Given the reproducibility of these results across two independent trials and the statistical significance of our findings, this study paves the way for further investigations into the use of electric fields in PD treatment strategies.

Future Work¶

This study opens several avenues for future research. First, further investigation is needed to determine the precise molecular mechanisms by which the electric field disrupts alpha-synuclein aggregation. Future studies could employ advanced techniques such as cryo-electron microscopy or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy to elucidate the structural changes in alpha-synuclein upon exposure to electric fields. Additionally, exploring the effects of varying electric field strengths and durations on aggregation could help optimize the conditions for therapeutic efficacy.

It will also be important to assess the long-term effects of electric field exposure on C. elegans neuromuscular health and longevity. Since the nematode has a relatively short lifespan (2-3 weeks), examining whether repeated or prolonged electric field exposure leads to any cumulative effects or negative consequences on worm health will be crucial in evaluating the viability of this approach for PD treatment.

Furthermore, the applicability of these findings to mammalian models of Parkinson’s disease warrants exploration. While C. elegans provides a powerful model system for initial screenings, the translation of these findings to higher organisms with more complex nervous systems is essential for determining the potential of electric field-based therapies in humans. Preclinical studies in rodent models of PD could provide more relevant data on the therapeutic potential of this approach.

Finally, combining electric field exposure with other therapeutic modalities, such as pharmacological treatments or genetic interventions, could provide synergistic benefits in treating Parkinson’s disease. Investigating how the electric field interacts with existing PD therapies may lead to more comprehensive and effective treatment strategies.

This work was supported and funded by the North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics with the help of mentor James Happer.

Copyright © 2024 Sarkar. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, which enables reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the creator.

- CGC

- Caenorhabditis Genetics Center

- MD

- Molecular Dynamics

- NGM

- Nematode growth medium

- PD

- Parkinson's disease

- YFP

- Yellow fluorescent protein

- Poewe, W., Seppi, K., Tanner, C. M., Halliday, G. M., Brundin, P., Volkmann, J., Schrag, A.-E., & Lang, A. E. (2017). Parkinson disease. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 3(1). 10.1038/nrdp.2017.13

- Pringsheim, T., Jette, N., Frolkis, A., & Steeves, T. D. L. (2014). The prevalence of Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Movement Disorders, 29(13), 1583–1590. 10.1002/mds.25945

- Spillantini, M. G., Crowther, R. A., Jakes, R., Hasegawa, M., & Goedert, M. (1998). α-Synuclein in filamentous inclusions of Lewy bodies from Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 95(11), 6469–6473. 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6469

- Corsi, A. K., Wightman, B., & Chalfie, M. (2015). A Transparent Window into Biology: A Primer on Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics, 200(2), 387–407. 10.1534/genetics.115.176099

- Dexter, P. M., Caldwell, K. A., & Caldwell, G. A. (2012). A Predictable Worm: Application of Caenorhabditis elegans for Mechanistic Investigation of Movement Disorders. Neurotherapeutics, 9(2), 393–404. 10.1007/s13311-012-0109-x

- (1986). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. B, Biological Sciences, 314(1165), 1–340. 10.1098/rstb.1986.0056

- Xue, D., Finney, M., Ruvkun, G., & Chalfie, M. (1992). Regulation of the mec-3 gene by the C.elegans homeoproteins UNC-86 and MEC-3. The EMBO Journal, 11(13), 4969–4979. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05604.x

- van Ham, T. J., Thijssen, K. L., Breitling, R., Hofstra, R. M. W., Plasterk, R. H. A., & Nollen, E. A. A. (2008). C. elegans Model Identifies Genetic Modifiers of α-Synuclein Inclusion Formation During Aging. PLoS Genetics, 4(3), e1000027. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000027

- Spillantini, M. G., Schmidt, M. L., Lee, V. M.-Y., Trojanowski, J. Q., Jakes, R., & Goedert, M. (1997). α-Synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature, 388(6645), 839–840. 10.1038/42166

- Razzokov, J., Fazliev, S., Makhkamov, M., Marimuthu, P., Baev, A., & Kurganov, E. (2023). Effect of Electric Field on α-Synuclein Fibrils: Revealed by Molecular Dynamics Simulations. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(7), 6312. 10.3390/ijms24076312

- Lavorato, M., Mathew, N. D., Shah, N., Nakamaru-Ogiso, E., & Falk, M. J. (2021). Comparative Analysis of Experimental Methods to Quantify Animal Activity in <em>Caenorhabditis elegans</em> Models of Mitochondrial Disease. Journal of Visualized Experiments, 170. 10.3791/62244

- Aguilar, A. A., Ho, M. C., Chang, E., Carlson, K. W., Natarajan, A., Marciano, T., Bomzon, Z., & Patel, C. B. (2021). Permeabilizing Cell Membranes with Electric Fields. Cancers, 13(9), 2283. 10.3390/cancers13092283

- Minakaki, G., Krainc, D., & Burbulla, L. F. (2020). The Convergence of Alpha-Synuclein, Mitochondrial, and Lysosomal Pathways in Vulnerability of Midbrain Dopaminergic Neurons in Parkinson’s Disease. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology, 8. 10.3389/fcell.2020.580634

- Vargas-Rosales, P. A., D’Addio, A., Zhang, Y., & Caflisch, A. (2023). Disrupting Dimeric β-Amyloid by Electric Fields. ACS Physical Chemistry Au, 3(5), 456–466. 10.1021/acsphyschemau.3c00021

- Wu, H., Ghaani, M. R., Futera, Z., & English, N. J. (2022). Effects of Externally Applied Electric Fields on the Manipulation of Solvated-Chignolin Folding: Static- versus Alternating-Field Dichotomy at Play. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 126(2), 376–386. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.1c06857