Exploring The Gut-Brain Axis in C. elegans— Probiotics as a Therapeutic Approach to Alpha-Synuclein Aggregation in Parkinson's Disease

Abstract¶

While neurological diseases have traditionally been thought to originate in the brain, emerging evidence suggests that this may not always be the case. Parkinson’s Disease (PD) is a debilitating neurodegenerative disorder characterized by a shortened lifespan, motor dysfunction, and the pathological accumulation of the protein alpha-synuclein. Although the neurobiological mechanisms underlying PD remain unclear, recent studies point to the gut-brain axis in alpha-synuclein aggregation, suggesting the gut microbiome’s role in disease onset. Disturbances in this axis are associated with the production of toxic metabolites, neuroinflammation, and increased gut permeability—all contributing to alpha-synuclein pathology. Since probiotics are known for restoring gut microbiota balance and reducing inflammation, they may play a key role in mitigating these effects. Hence, with the use of Caenorhabditis elegans models of PD, this study explored the therapeutic potential of probiotics to extend lifespan, improve motor function, and reduce alpha-synuclein aggregation. PD symptoms were induced in the transgenic C. elegans strain NL5901 via exposure to Escherichia coli strain MC4100, which was followed by treatment with varying dosages of probiotic supplementation. Thrashing and lifespan assays were used to measure motor function and longevity, while fluorescence microscopy was used to quantify alpha-synuclein aggregation. While no statistically significant differences were observed among the dosage groups (p > 0.05), probiotic treatment significantly reduced alpha-synuclein aggregation (p < 0.001), enhanced motor function (p < 0.001), and accelerated reproduction compared to untreated controls. Therefore, these findings support the potential of probiotics as modulators of the gut-brain axis, serving as a promising therapeutic avenue for PD and other neurodegenerative diseases.

Introduction¶

Although neurodegenerative diseases have been researched extensively, their treatment often falls short. Parkinson’s Disease (PD) is a common neurodegenerative disorder that impacts millions of lives in the world each year, imposing significant burdens on affected individuals, caregivers, and healthcare systems. In the past, research has identified the abnormal aggregation of alpha-synuclein, a U3 ubiquitin ligase protein, as the root cause of neuronal cytotoxicity and death Lotharius & Brundin, 2002, resulting in the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the brain’s substantia nigra Surmeier, 2018. The lack of dopamine contributes to the emergence of Parkinson’s-like symptoms, which include a spectrum of motor difficulties, such as tremors, bradykinesia, and rigidity, alongside non-motor symptoms, including autonomic dysfunction and cognitive impairment. These complications culminate into a reduced lifespan and overall worsened quality of life, with their impact becoming more pronounced as individuals age Golbe & Leyton, 2018. Despite the existence of treatment modalities that focus on alleviating PD symptoms, these methods are often expensive, unsafe, and fail to address the believed underlying cause: the build-up of alpha-synuclein. In the case of PD, the excessive aggregation of alpha-synuclein can cause neuronal dysfunction and death through mechanisms that include mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and impaired protein clearance pathways Picca et al., 2020. Reducing levels of alpha-synuclein in PD patients has shown to improve motor symptoms and extend lifespan, raising the need for a treatment that effectively targets its aggregation Park et al., 2024. However, what if our gut holds the solution? Neurobiologists theorize that imbalances in the gut microbiome are associated with PD, which can be attributed to the bidirectional relationship between the gastrointestinal tract (the enteric nervous system) and the central nervous system. The gut-brain-axis hypothesis posits that the gut and brain are connected via the vagus nerve, thus allowing for the direct transfer of metabolites, hormones, and immune signals Han et al., 2022. Recent research has implicated that an overabundance of Desulfovibrio (DSV) bacteria is connected to PD pathogenesis. When these bacteria produce toxic metabolites, including hydrogen sulfide (H2S), lipopolysaccharide, and magnetite, they contribute to the oligomerization and aggregation of alpha-synuclein Huynh et al., 2023. These alpha-synuclein clumps can then travel up the vagus nerve to the brain, where they contribute to neurodegeneration Holmqvist et al., 2014. Probiotics have recently exhibited therapeutic potential for the treatment of PD through regulating the gut microbiome Tan et al., 2020. Numerous probiotics have shown to yield a positive effect. Feeding probiotic Bacillus subtilis PXN21 to an alpha-synuclein-expressing Caenorhabditis elegans model of PD resulted in reduced alpha-synuclein accumulation in the host Goya et al., 2020. The oral administration of the probiotic Clostridium butyricum has also demonstrated neuroprotective effects in PD mice models, improving motor deficits and reducing gut dysbiosis Sun et al., 2021. In a double-blind clinical trial in Iran, 60 PD patients were treated with probiotics supplementation (probiotics: Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium composition, encapsulated Lactobacillus reuteri, and Lactobacillus fermentum) for 12 weeks to evaluate its effects on exercise—and found a reduction in Movement Disorders Society-Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale scores compared to the placebo. The effect on encapsulated probiotic dosage, however, has yet to be evaluated in the context of PD symptoms. Due to their well-studied nervous systems, accessible genetic manipulation, optical transparency, and quantifiable locomotion, C. elegans are effective model organisms for studying Parkinson’s Disease Tseng et al., 2023. The NL5901 strain serves as a transgenic model which can be utilized to visualize alpha-synuclein aggregation through fluorescence Shamsuzzama et al., 2017. Additionally, MC4100 is a laboratory strain of Escherichia Coli (E. Coli) that produces curli proteins and thus induces PD-like symptoms Lim et al., 2012. Since it can serve as a nucleating agent for misfolded proteins, create a microenvironment conducive to amyloid formation, and interact with cells to encourage the spread of alpha-synuclein across the gut-brain axis, exposure to MC4100 can start the development of PD pathogenesis Sampson et al., 2020. Its role in initiating PD pathogenesis makes it a useful benchmark for studying the effects of other experimental conditions. Hence, this study evaluated whether probiotic supplementation with varying dosages reduces alpha-synuclein aggregation, improves motor symptoms, and extends lifespan in C. elegans models of Parkinson’s disease. With the goal of shedding light on the complex molecular mechanisms underlying PD, this study investigated the use of probiotics as an effective preventative medicine, thus providing valuable insights into the gut-brain connection and its role in neurodegeneration. As the prevalence of PD continues to rise, particularly in aging populations, the development of affordable and effective disease-modifying therapies is urgently needed to alleviate suffering for millions of affected individuals across the globe—suggesting that something as simple as probiotics could be the solution.

Methods¶

C. elegans & Bacterial Strains¶

C. elegans NL5901 pkIs2386 [Punc-54::α-synuclein::YFP + unc-119(+)] were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC). Aside from C. elegans (or, nematodes), several bacterial strains were used in this study, with Escherichia coli OP50 obtained from CGC and Escherichia coli MC4100 provided by the E. coli Genetic Resource Center in Cheshire, Connecticut. The curli-producing E. coli MC4100 was cultured and stored in Luria broth (LB) at 37°C prior to usage Son & Taylor, 2012. Regarding treatment, Spring Valley probiotic dietary supplements were obtained from Walmart in Morganton, North Carolina and stored at 25°C prior to experimentation, containing Lactobacillus paracasei NI327, Lactobacillus casei NI320, Lactobacillus rhamnosus NI332, Lactobacillus plantarum NI329, Bifidobacterium longum NI316, Lactobacillus acidophilus NI317, Streptococcus thermophilus NI335, Bifidobacterium breve NI312, Bifidobacterium bifidum NI311, and Lactococcus lactis NI334. Each capsule contained a concentration of 1010 CFU/mL of the mixed probiotic bacteria.

C. elegans Growth Conditions¶

Nematodes were handled in 35 mm NGM plates according to standard practices, and they were grown on E. coli OP50 at 25°C until the L4 stage Stiernagle, 2019. Prior to experimentation, 50 µL of 100 µM floxuridine (FUdR), a DNA synthesis inhibitor that prevents the production of offspring, was added to 12 new NGM plates. The 12 NGM plates were then divided into 4 groups labeled the following: untreated, 106 probiotic (PB) treatment, 107 PB treatment, and 108 PB treatment.

Diet Preparation & Administration¶

Tenfold serial dilutions were conducted to prepare the probiotic solution for each treatment group (Microbiologics Dilution Guide). The contents within 1 probiotic capsule were removed and combined with 1 mL of molecular grade water. The solution was then centrifuged for 3 minutes, and the supernatant was utilized for dilution. One mL of the solution was removed and added to 9 mL of molecular grade water, and the dilution continued until concentrations of 106 , 107 , and 108 CFU/mL were reached. After preparing the dilutions, 60 µL of each probiotic solution was seeded at the center of 9 out of 12 NGM plates: 3 plates received 106 CFU/mL PB, 3 received 107 CFU/mL PB, and 3 received 108 CFU/mL PB. All 12 NGM plates were seeded with MC4100 E. coli to induce alpha-synuclein aggregation in the nematodes. Fifteen nematodes were transferred to each plate, using MC4100 E. coli as a picking tool adhesive Stiernagle, 2019. Once the nematodes were shifted to their new diet, they were transferred to new plates every two days thereafter to avoid bacterial contamination Stiernagle, 2019.

Confirming The Presence of Lactic Acid Bacteria¶

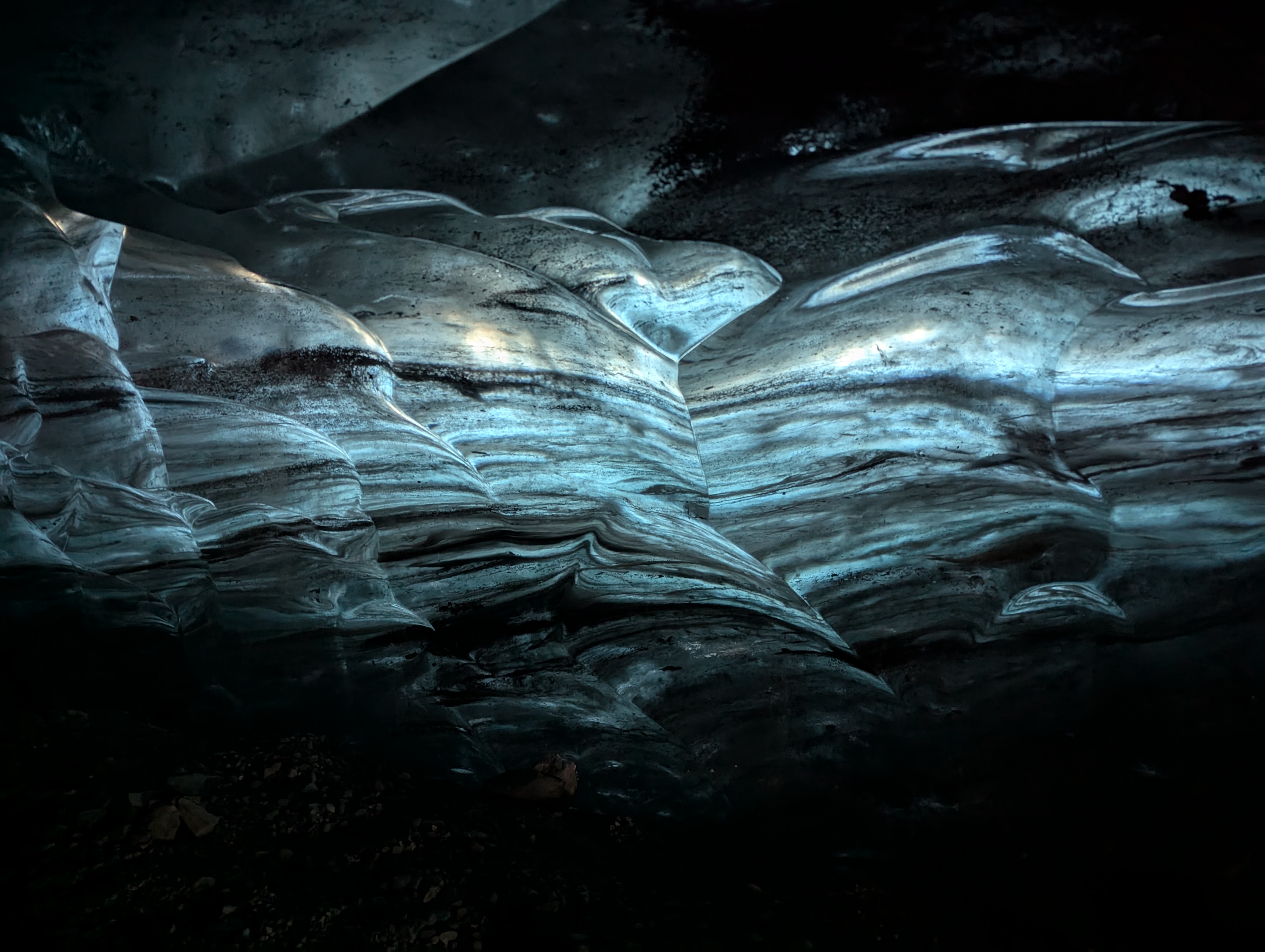

Lactic Acid bacteria R-CARDS were utilized to confirm the presence of lactic acid bacteria in the probiotic capsule. The detection was indicated by a color change and the appearance of quantifiable dots, which corresponded to bacterial colonies. To estimate the bacterial concentration, 1 mL of the 103 CFU/mL solution was added to the card, allowing for the approximation of viable lactic acid bacteria.

Lifespan Assay¶

After the nematodes were confirmed to be age-synchronized, they were assessed daily for death, which was verified when they failed to respond to a gentle tap on the head with a platinum wire Hughes et al., 2022. The average number of live worms was recorded for each plate and plotted on a bar graph using GraphPad Prism.

Thrashing Assay¶

The motility of the worms was assessed on Days 3, 6, and 8. On each day, 5 nematodes from each plate were placed into the prepared M9 buffer (40 µL) on an unseeded 35 mm NGM plate at 25 °C. The number of full-body bends per 30 seconds was quantified for each nematode using a Teledyne Lumenera INFINITY ANALYZE 7 microscope connected to an INFINITY camera and analyzed with INFINITY ANALYZE software Hughes et al., 2022. In this experiment, a full body bend was defined as the nematode’s head and tail making contact. The averages of the number of full body bends per 30 seconds were calculated and plotted for each respective group. These averages were recorded at the Larval 4 (L4), young adult, and adult stage to visualize changes in the worms’ condition over time. Three bar graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism to determine whether the treatment of the substance on the MC4100 bacteria led to a significant improvement in outcomes for the worms’ motor abilities. Error bars were calculated as the standard error of mean (SEM), and a line graph was compiled to exhibit the changes the treated and untreated worms experienced over time.

Fluorescence Microscopic Analysis¶

Alpha-synuclein aggregation was represented by the concentration of green fluorescent protein (GFP) fluorescence. On Days 5 and 7, five nematodes from each plate underwent fluorescence microscopy imaging. The nematodes were imaged one at a time, using a Teledyne Lumenera INFINITY ANALYZE 7 microscope at 40× magnification. Maximal projections of confocal images were captured with INFINITY ANALYZE 7 Software at peak exposure in the single GFP channel. To determine the extent of the aggregation, ImageJ v1.51 was used with no additional plugin. The drawing feature within ImageJ was utilized to outline the nematode and obtain the area, mean, integrated density (IntDensity), and the raw integrated density (RawIntDensity). The same parameters were obtained from the surrounding environment by outlining portions of the image background (of any size). The nematode’s Corrected Total Cell Fluorescence (CTCF) was then calculated with the following formula: CTCF = Integrated density - (Area of selected cell x Mean fluorescence of background readings) The average of the calculated values was derived from each group (Measuring cell fluorescence using ImageJ). Bar graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism to visually represent the data across different groups, and t-tests were employed to compare means between treatment conditions and assess the significance of any observed differences. Error bars were calculated as the standard error of mean (SEM).

Figure 1:Untreated nematode (did not receive probiotic treatment) imaged with fluorescence microscopy and INFINITY ANALYZE X software.

Results & Discussion¶

Confirming The Presence of Lactic Acid Bacteria¶

The presence of Lactic Acid bacteria in the probiotic capsules was confirmed by the appearance of colored dots on the R-CARDs, as shown in Figure 2. The concentration derived from the card was approximated as 103 CFU/mL, which confirmed the reliability of the serial dilutions.

Figure 2:A Lactic Acid Bacteria R-CARD displaying the presence of Lactic Acid bacteria obtained from 103 CFU/mL of 1 Spring Valley probiotic capsule. Each blue dot represents a colony of bacteria, and the dots in each square were quantified to yield a total concentration of approximately 103. This confirmed the accuracy of the serial dilutions.

Lifespan Assay¶

Despite the presence of FUdR in all the plates, the worms were observed reproducing during the experiment. The nematodes in the PB treatment groups reproduced on Day 7, and the untreated nematodes reproduced on Day 8. As a result, the lifespan assay could not be conducted. Differences in the timing of reproduction between the untreated and treated groups were noted; however, the possibility of probiotics extending nematode lifespan could not be determined in this assay.

Thrashing Assay¶

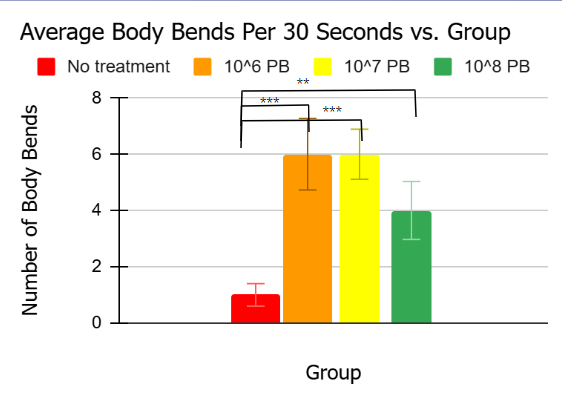

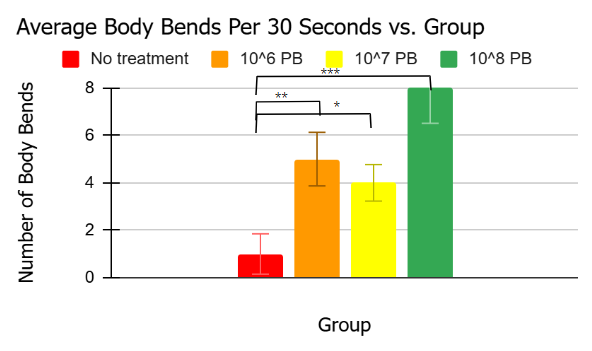

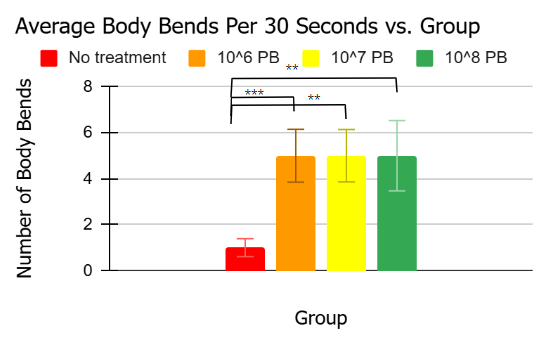

As shown in Figure 3, Figure 4, and Figure 5, the untreated groups exhibited a significantly lower average number of thrashes compared to the PB treatment groups on Days 3, 6, and 8. No statistically significant difference was observed across the probiotic treatment groups throughout the course of the experiment. These conclusions were determined through the implementation of t-tests and calculation of p-value.

Figure 3:Probiotic treatment increased thrashing behavior in Day 3 worms. The solid red bar represents the untreated worms, which were solely exposed to MC4100 E. coli. The orange bar represents the treated worms, which were exposed to 106 CFU/mL probiotic supplementation alongside MC4100. The yellow and green bars represent the treated worms exposed to the 107 and 108 concentrations of the probiotic supplementation, respectively. The treated worms experienced a significant (p<0.01) number of thrashes per 30 seconds compared to the untreated worms and experienced an insignificant difference in thrashes amongst themselves. In terms of p-value, one star signifies p<0.05, two stars signifies p<0.01, and three stars signifies p<0.001.

Figure 4:Probiotic treatment continued to increase thrashing behavior in Day 6 worms. The solid red bar represents the untreated worms, which were solely exposed to MC4100 E. coli. The orange bar represents the treated worms, which were exposed to 106 CFU/mL probiotic supplementation alongside MC4100. The yellow and green bars represent the treated worms exposed to the 107 and 108 concentrations of the probiotic supplementation, respectively. The 108 worms presented the most statistically significant difference in the number of thrashes per 30 seconds, with p<0.001. Overall, the treated worms experienced a significant (p<0.05) number of thrashes compared to the untreated worms and experienced an insignificant difference in thrashes amongst themselves. In terms of p-value, one star signifies p<0.05, two stars signifies p<0.01, and three stars signifies p<0.001.

Figure 5:Probiotic treatment remained consistent with increasing thrashing behavior in Day 8 worms. The solid red bar represents the untreated worms, which were solely exposed to MC4100 E. coli. The orange bar represents the treated worms, which were exposed to 106 CFU/mL probiotic supplementation alongside MC4100. The yellow and green bars represent the treated worms exposed to the 107 and 108 concentrations of the probiotic supplementation, respectively. Overall, the treated worms experienced a significant (p<0.05) number of thrashes per 30 seconds compared to the untreated worms and experienced an insignificant difference in thrashes amongst themselves. The worms in treatment groups yielded the same average number of thrashes, presenting no statistically significant difference (p>0.05). In terms of p-value, one star signifies p<0.05, two stars signify p<0.01, and three stars signify p<0.001.

Fluorescence Microscopic Analysis¶

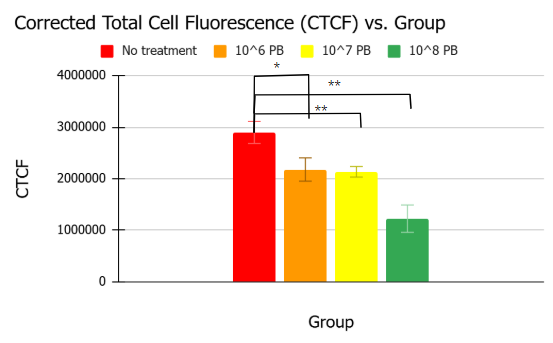

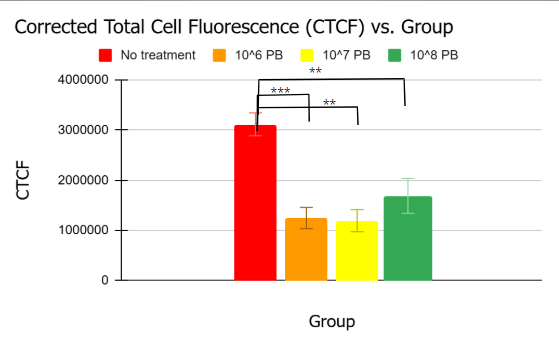

Based on the differences in CTCF levels, the treated nematodes exhibited a lower level of alpha-synuclein aggregation compared to the untreated nematodes, regardless of what PB concentration they received. This trend was recorded on Day 5 and continued on Day 7, where an even larger disparity in GFP fluorescence was observed. On Day 7, however, 106 and 107 PB treatment groups displayed the lowest CTCF levels. No statistically significant difference was observed in the CTCF levels across treatment groups. These conclusions were determined through implementing t-tests and calculating p-value.

Figure 6:Probiotic treatment presented lower levels of alpha-synuclein aggregation for Day 5 worms. The solid red bar represents the untreated worms, which were solely exposed to MC4100 E. coli. The orange bar represents the treated worms, which were exposed to 106 CFU/mL probiotic supplementation alongside MC4100. The yellow and green bars represent the treated worms exposed to the 107 and 108 concentrations of the probiotic supplementation, respectively. The group that received the highest probiotic concentration presented the lowest average CTCF value—a value significantly lower than that of the untreated group (p<0.01). Overall, all treatment groups experienced significantly lower levels of aggregation compared to the untreated group (p<0.05). In terms of p-value, one star signifies p<0.05, two stars signify p<0.01, and three stars signify p<0.001.

Figure 7:Probiotic treatment presented lower levels of alpha-synuclein aggregation for Day 7 worms. The solid red bar represents the untreated worms, which were solely exposed to MC4100 E. coli. The orange bar represents the treated worms, which were exposed to 106 CFU/mL probiotic supplementation alongside MC4100. The yellow and green bars represent the treated worms exposed to the 107 and 108 concentrations of the probiotic supplementation, respectively. Overall, all treatment groups experienced significantly lower levels of aggregation compared to the untreated group (p<0.01). The group that received the lowest probiotic concentration presented the lowest average CTCF value, greatly differing from the untreated group’s (p<0.001). In terms of p-value, one star signifies p<0.05, two stars signify p<0.01, and three stars signify p<0.001.

These results showcase the potential of probiotic supplementation in improving motility and decreasing alpha-synuclein aggregation in nematodes. The probiotics may have countered the pathogenesis of PD, resulting in improved physiological resilience and reduced disease progression. These findings, in turn, support the emerging theory that probiotics hold potential beneficial effects on molecular and cellular pathways, as well as behavioral outcomes, in preclinical and clinical studies of PD Leta et al., 2021. Although the lifespan assay could not be conducted and the application of FUdR had not demonstrated efficacy, the nematodes that received PB treatment reproduced approximately 24 hours earlier than the untreated nematodes, which suggests an underlying relationship between probiotics and vitality. This study also confirmed the use of MC4100 bacteria as a positive control in PD experimentation. Future studies can continue to rely on this bacteria to initiate alpha-synuclein aggregation and evaluate the efficacy of potential therapeutic agents, such as probiotics, in mitigating the associated neurodegenerative effects. In this case, the dosage did not impact the efficacy of the probiotic treatment. This calls for further experimentation to determine the minimum dosage that yields a statistically significant difference. Additionally, future studies should confirm the presence of MC4100 bacteria and the probiotic bacteria within the nematodes’ gut microbiomes through microscopy or sequencing techniques. This imaging will assist with determining the localization and interaction of the probiotics within the host’s gut. Such follow-up interventions will enable us to understand the mechanisms at play and refine probiotic-based strategies for neuroprotection. Overall, this study adopted a different approach with studying PD pathogenesis. Targeting the imbalances within the gut microbiome, utilizing a widely available ingestible product as preventative treatment, and focusing on the impact on various dosages provides a unique lens that emphasizes the gut-brain connection and its potential for therapeutic interventions. These findings align with the growing claim that probiotics wield neuroprotective effects—offering promising avenues for non-invasive treatment strategies. It is crucial to acknowledge, however, that the study faced several limitations. The inability to conduct a lifespan assay and the lack of efficacy in FUdR application limited comprehensive analysis, which left certain potential effects unexplored. Since the study also could not confirm bacterial presence in the gut microbiomes, it lacked verification that the probiotics successfully reached their target location. The viability of the probiotics may also have been impacted by environmental conditions, such as fluctuations in temperature, inadequate nutrient availability, and prolonged storage times, which may have compromised bacterial integrity and limited their impact on nematode health.

Conclusion¶

Ultimately, the administration of probiotic supplementation in C. elegans resulted in accelerated reproduction, greater motility, and reduced alpha-synuclein aggregation. The difference in dosage did not result in a statistically significant difference in any of the three factors across the probiotic treatment groups; however, these groups showed improved PD symptoms compared to the untreated group. Thus, the presence of probiotics (in concentrations of 106, 107, and 108 CFU/mL) is sufficient to discourage PD pathogenesis. Administration of the probiotic treatments at the start of the experiment allowed for the evaluation of probiotics as a preventative treatment, providing insight into its ability to address the issue of alpha-synuclein aggregation—the root cause of PD. However, numerous questions remain unanswered. What are the specific properties that enable probiotics to alleviate PD symptoms on a neurological level? Would a probiotic mixture be more effective in treating PD compared to isolated Lactic Acid bacteria? What if probiotics were administered post-pathogenesis? Most importantly, though, how can probiotics be leveraged to prevent neurodegeneration and enhance human health? Although this study provides valuable insights into their efficacy in treating PD, future studies will hopefully produce answers to these questions—enabling us to determine effective therapeutic strategies for PD and other neurodegenerative diseases. Since current treatment methods remain expensive and largely inaccessible for the time being, the possibility of probiotics as preventative medicine offers a promising solution—in neurodegenerative treatment and beyond.

Copyright © 2024 Urmanova. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, which enables reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the creator.

- C. elegans

- Caenorhabditis elegans

- CFU

- colony forming unit

- CGC

- Caenorhabditis Genetics Center

- CTCF

- Corrected Total Cell Fluorescence

- DSV

- Desulfovibrio

- E. Coli

- Escherichia Coli

- FUdR

- floxuridine

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein

- H2S

- hydrogen sulfide

- IntDensity

- integrated density

- L4

- Larval 4

- NGM

- Nematode Growth Media

- PB

- probiotic

- PD

- Parkinson's Disease

- pkIs2386

- Punc-54::α-synuclein::YFP + unc-119(+)

- RawIntDensity

- raw integrated density

- SEM

- standard error of mean

- Lotharius, J., & Brundin, P. (2002). Pathogenesis of parkinson’s disease: dopamine, vesicles and α-synuclein. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 3(12), 932–942. 10.1038/nrn983

- Surmeier, D. J. (2018). Determinants of dopaminergic neuron loss in Parkinson’s disease. The FEBS Journal, 285(19), 3657–3668. 10.1111/febs.14607

- Golbe, L. I., & Leyton, C. E. (2018). Life expectancy in Parkinson disease. Neurology, 91(22), 991–992. 10.1212/wnl.0000000000006560

- Picca, A., Calvani, R., Coelho-Junior, H. J., Landi, F., Bernabei, R., & Marzetti, E. (2020). Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Oxidative Stress, and Neuroinflammation: Intertwined Roads to Neurodegeneration. Antioxidants, 9(8), 647. 10.3390/antiox9080647

- Park, H., Kam, T.-I., Dawson, V. L., & Dawson, T. M. (2024). α-Synuclein pathology as a target in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature Reviews Neurology, 21(1), 32–47. 10.1038/s41582-024-01043-w

- Han, Y., Wang, B., Gao, H., He, C., Hua, R., Liang, C., Zhang, S., Wang, Y., Xin, S., & Xu, J. (2022). Vagus Nerve and Underlying Impact on the Gut Microbiota-Brain Axis in Behavior and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Journal of Inflammation Research, Volume 15, 6213–6230. 10.2147/jir.s384949

- Huynh, V. A., Takala, T. M., Murros, K. E., Diwedi, B., & Saris, P. E. J. (2023). Desulfovibrio bacteria enhance alpha-synuclein aggregation in a Caenorhabditis elegans model of Parkinson’s disease. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 13. 10.3389/fcimb.2023.1181315

- Holmqvist, S., Chutna, O., Bousset, L., Aldrin-Kirk, P., Li, W., Björklund, T., Wang, Z.-Y., Roybon, L., Melki, R., & Li, J.-Y. (2014). Direct evidence of Parkinson pathology spread from the gastrointestinal tract to the brain in rats. Acta Neuropathologica, 128(6), 805–820. 10.1007/s00401-014-1343-6

- Tan, A. H., Hor, J. W., Chong, C. W., & Lim, S. (2020). Probiotics for Parkinson’s disease: Current evidence and future directions. JGH Open, 5(4), 414–419. 10.1002/jgh3.12450

- Goya, M. E., Xue, F., Sampedro-Torres-Quevedo, C., Arnaouteli, S., Riquelme-Dominguez, L., Romanowski, A., Brydon, J., Ball, K. L., Stanley-Wall, N. R., & Doitsidou, M. (2020). Probiotic Bacillus subtilis Protects against α-Synuclein Aggregation in C. elegans. Cell Reports, 30(2), 367-380.e7. 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.12.078

- Sun, J., Li, H., Jin, Y., Yu, J., Mao, S., Su, K.-P., Ling, Z., & Liu, J. (2021). Probiotic Clostridium butyricum ameliorated motor deficits in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease via gut microbiota-GLP-1 pathway. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 91, 703–715. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.10.014

- Tseng, Y.-L., Lu, P.-C., Lee, C.-C., He, R.-Y., Huang, Y.-A., Tseng, Y.-C., Cheng, T.-J. R., Huang, J. J.-T., & Fang, J.-M. (2023). Degradation of neurodegenerative disease-associated TDP-43 aggregates and oligomers via a proteolysis-targeting chimera. Journal of Biomedical Science, 30(1). 10.1186/s12929-023-00921-7

- Shamsuzzama, Kumar, L., & Nazir, A. (2017). Modulation of Alpha-synuclein Expression and Associated Effects by MicroRNA Let-7 in Transgenic C. elegans. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience, 10. 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00328

- Lim, J. Y., May, J. M., & Cegelski, L. (2012). Dimethyl Sulfoxide and Ethanol Elicit Increased Amyloid Biogenesis and Amyloid-Integrated Biofilm Formation in Escherichia coli. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 78(9), 3369–3378. 10.1128/aem.07743-11

- Sampson, T. R., Challis, C., Jain, N., Moiseyenko, A., Ladinsky, M. S., Shastri, G. G., Thron, T., Needham, B. D., Horvath, I., Debelius, J. W., Janssen, S., Knight, R., Wittung-Stafshede, P., Gradinaru, V., Chapman, M., & Mazmanian, S. K. (2020). A gut bacterial amyloid promotes α-synuclein aggregation and motor impairment in mice. eLife, 9. 10.7554/elife.53111