In Silico Exploration of L-Valine Ester Prodrug Designs for Enhanced Pharmacokinetics in BCS Class IV Nucleoside Antivirals.

Abstract¶

Nucleoside derivatives are among the few families of molecules with antiviral properties. However, pharmacokinetic limitations have historically limited their capabilities for oral administration, the preferred administration mechanism with historically improved outcomes, versatility, and ability for at-home administrations. In recent years, Valacyclovir and Valganciclovir have demonstrated how the addition of a valine promoiety to nucleoside antivirals allow the drugs to overcome oral pharmacokinetic boundaries through the usage of the PepT1 pathways as prodrugs. Torcitabine is a highly potent hepatitis B virus inhibitor, but faced limited usage in countries with prevalent HBV cases due to requirements for intravenous administration. Cyclopropavir is a cytomegalovirus inhibitor like Ganciclovir, but has pre-clinically exhibited multiple advantages, including 10-fold increases in potency, half-life, and reduced complications. Using Gaussian 16, B3LYP, and a 6-31g basis set, we conducted molecular orbital, natural bond orbital, and bond order calculations to predict key indicators of bioavailability, including dissociation rates, electrostatic binding affinity, and bond stability. Then, key quantitative structure activity relationship (QSAR) properties and molecular docking affinities were obtained from Optibrium’s StarDrop Software to predict effectiveness when binding to important target proteins, including the PepT1 receptor and Valacyclovir Hydrolase enzyme. Valtorcitabine and Valcyclopropavir both exhibited high pharmacokinetic potential for use as oral medications, with similar properties to Valacyclovir and Valganciclovir. The results of this study support future in vivo experimentation for both drugs as drug candidates for hepatitis B virus and cytomegalovirus, respectively.

Introduction¶

Nucleoside-derived molecules are the most prominent group of antiviral drug candidates, chosen for their rare ability to mimic DNA material to attract viral enzymes Markovic et al., 2020. However, most nucleoside derivatives are classified by the Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) as class IV drugs. Class IV drugs exhibit numerous unfavorable characteristics (low solubility and permeability, high presystemic metabolism, efflux transport) that impede safe oral delivery with an effective bioavailability, limiting much of their historical clinical usage to intravenous administration in hospital settings. Due to the significant financial and health advantages of oral medications, more studies have emerged on the development of prodrugs, modified drugs made to achieve high oral bioavailability, of many existing Class IV drugs that require intravenous administration. Prodrugs are defined as biologically inactive drug molecules that undergo an enzymatic and/or chemical transformation in vivo to release an active parent drug Vig & Rautio, 2011. Prodrugs are created by attaching a promoiety, a chemical group that enhances the molecule’s absorption, distribution, or stability. Prodrugs allow for oral distribution by enabling absorption into the bloodstream, then using enzymatic cleavage to remove the promoiety and release the parent drug, which can freely move through the bloodstream into the target site. Quantitative measures of a prodrug’s effectiveness come from its ability to improve the parent drug’s absorption proportion. They must also be highly stable to prevent unwanted metabolism but be able to rapidly convert into the parent drug after reaching the bloodstream.

Nucleoside-derivatives are incredibly promising for prodrug studies due to their compatibility with promoieties and the need for orally-administered antivirals. This interest and compatibility have led to multiple prodrug forms of nucleoside-derived antivirals being clinically approved and incredibly successful in the pharmaceutical markets. Acyclovir and Ganciclovir, for example, were among the first successful antiviral drugs, and are highly potent against Herpes Simplex Virus and Cytomegalovirus, respectively. While both had essentially no function as oral drugs and had to be administered intravenously, the prodrug variants of both these molecules, Valacyclovir and Valganciclovir, have bioavailabilities greater than 50%, and receive millions of prescriptions annually due to their improved convenience and effectiveness.

The selection of a prodrug’s promoiety is based on the parent drug’s needs and available functional groups. In this regard, amino acid promoieties have proven to be highly advantageous and compatible with the nucleoside derivative family of drugs, and Valacyclovir and Valganciclovir both utilize a valine promoiety. Research by Beutner, 1995 has revealed that, despite the improved yet still suboptimal ADME parameters, the addition of an amino acid promoiety allows the prodrugs to bind to the intestinal PepT1 and PepT2 receptors, which are used for active transport of oligopeptides from the intestines into the bloodstream. Through these L-valine ester prodrug designs, Beutner observed that Valacyclovir can achieve an approximate oral bioavailability of 54.5%, 3-5 times greater than its parent. Similarly, Valganciclovir has an oral bioavailability of 60%, as compared to Ganciclovir’s 5-8% (PubChem (2025)Umapathy et al. (2004)).

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is among the most prevalent viral agents in the world. A leading cause of mortality in immunocompromised patients, CMV infects one in every 100-150 newborns, making it the most common congenital infection in most countries Demmler-Harrison, 2009. Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) is similarly prevalent, as approximately 296 million people are currently living with a chronic HBV infection, and 820,000 deaths annually are attributed to HBV-related complications Ahmad et al., 2020. With that said, Torcitabine has been preclinically found to be a potent nucleoside inhibitor against HBV and Cyclopropavir possesses high antiviral properties against CMV (Ahmad et al. (2020)Wu et al. (2009)). Both are BCS class IV drugs that, despite their in vitro antiviral properties, weren’t studied extensively as oral drug candidates, largely due to their poor pharmacokinetic properties as an oral medication. However, both drugs showed promise for high compatibility with the valine ester promoiety, having hydroxyl groups that could be masked by forming an ester bond with valine that could be broken by esterase enzymes like Valacyclovir Hydrolase in the blood.

The absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) properties of the prodrug derivatives, including LogP, polar surface area, pKa, etc. to predict the stability and solubility of the molecule as it travels through the gastrointestinal tract. We also conducted a molecular docking study of the prodrugs to quantify their ability to bind to the external PepT1 and PepT2 proteins, which is the primary mechanism for transmitting valine-based prodrugs into the bloodstream. Quantum calculations were run through Gaussian 16 to predict the stability and reactivity of the prodrugs as they are absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract, which were assessed qualitatively using a variety of electronic and orbital properties including HOMO-LUMO gaps, electrostatic potential models, bond order calculations, and natural population analysis. This study aimed to determine the effectiveness of Valtorcitabine and Valcyclopropavir as prodrugs relative to successful prodrugs like Valacyclovir and Valganciclovir, using this data to inform further in vivo research as oral drug candidates for HBV and CMV.

Computational Approach¶

Quantum Calculations

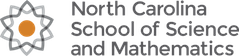

Figure 1:Molecules 1-8, 4 parent drugs and 4 prodrugs

Density functional theory (DFT) with the Lee-Yang-Parr correlation functional, denoted B3LYP, was used to execute the theoretical calculations Parr et al., 1979. All quantum chemistry was calculated using the quantum chemical package Gaussian 16 Frisch et al., 2016. Each calculation was run at the B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) level of theory to allow for timely calculation times given the number and size of the molecules included in this study (8 molecules each up to 26 heavy atoms). The North Carolina High School Computational Chemistry Server was used to organize and manage all jobs North Carolina High School Computational Chemistry Server, 2025. The starting geometries of all calculated molecules 1-8 in Figure 1 were designed in WebMO and then optimized. Vibrational frequency calculations were then run to confirm that the geometry optimizations were at the lowest energy states. With the confirmed geometry optimizations, molecular orbital calculations and natural bond order calculations were run for each molecule. Bond order calculations were run for prodrug molecules 5-8.

Molecular Orbital Calculation

First, a molecular orbital calculation was run to ascertain the magnitude of each molecule’s HOMO-LUMO gap. These values are obtained by measuring the difference in orbital energy between the highest-energy molecular orbital occupied by electrons (HOMO) and the lowest-energy molecular orbital unoccupied by electrons (LUMO). The HOMO and LUMO were visualized to predict the behavior of electrons in excited states, and their values were compared with literature values for Valacyclovir’s HOMO-LUMO gap B. et al., 2019. Using the same calculation, we visualized and interpreted the electrostatic potential maps of prodrug molecules 5-8 to predict the regional reactivities in specific biochemical reactions as molecules travel through the body. Specifically, the valine group was analyzed to make predictions of their efficacy for two key interactions: electrophilic sites for affinity to enzymatic nucleophilic attacks, and negatively charged regions that are likely to bind to positively charged PepT1 transporter residues.

Natural Bond Orbital (NBO)

A natural bond orbital calculation was run to predict how the addition of a valine promoiety affected the molecule’s ADME properties. Specifically, we used a natural population analysis to measure the extent to which the valine group masks the charges of the parent drug’s OH group. This reduction of charge was studied as it can help the molecule resist rapid excretion and increase absorption proportions.

Bond Order Calculation

A bond order calculation was run to measure the relative strengths and bond order of the prodrug’s ester linkage to make predictions of the inherent strength of the bond and its ability to resist dissociation prior to esterase enzyme exposure in the bloodstream. If the prodrug were to dissociate early, the drug’s total bioavailability would decrease because the parent drug could not enter the bloodstream without the valine promoiety.

QSAR and pKa Calculations

The second round of calculations used specialized medicinal chemistry software instead of quantum calculations. All calculations were run using Optibrium’s StarDrop software Besnard et al., 2012. To do so, Molecules 1-8 were coded into SMILES notation and uploaded into StarDrop software to calculate quantitative data of the pharmacokinetic properties of the molecules. Stardrop’s modeling tool ran calculations for LogP, TPSA, and various pKa values for molecules 1-8. The valine group does not enable the prodrugs to permeate cell membranes passively or effectively dissolve into solvents they otherwise couldn’t, but it does enable their active diffusion into the bloodstream. Knowing how the promoiety alters the parent drug’s ADME properties allows us to gauge the prodrug’s bioavailability, which is dependent on its stability and resistance to degradation. Because the gastrointestinal tract has multiple regions with varying pH environments, we calculated various pKa values, including the most acidic and basic values of each prodrug, to predict their behaviors in different pH environments.

Molecular Docking Calculations

To assess the ability of Valcyclopropavir and Valtorcitabine to bind to key proteins involved in the absorption of valine prodrugs, Stardrop’s SEESAR tool was used to calculate their binding affinity to PepT1, PepT2, and Valacyclovir Hydrolase. The binding sites of these three proteins were represented using the Protein Data Bank codes 7PMW, 9BIS, and 20CI (Lai et al. (2008)Parker et al. (2024)Ural-Blimke et al. (2019)). Valine-based prodrugs must interact with PepT1 and PepT2 proteins to be actively transported from the intestines into the bloodstream. Thus, to enter the bloodstream, it is imperative for Valtorcitabine and Valcyclopropavir to successfully bind to the receptors with similar magnitudes to Valacyclovir and Valganciclovir to use those pathways. Additionally, the enzyme primarily responsible for metabolizing Valacyclovir into Acyclovir is Valacyclovir Hydrolase; this enzyme is the primary esterase responsible for removing the valine group from the parent drug. The number of conformers each molecule had within the binding pocket and their respective binding affinities was calculated for each protein, measured in pKi.

Results and Discussion¶

Molecular Orbitals Analysis

The molecular orbital calculations were run using a 6-31G(d,p) basis set, and the results could be verified to a <5% margin of error compared to literature values of Valacyclovir’s HOMO-LUMO gap B. et al., 2019.

Table 1:HOMO-LUMO gap values

| Parent Drug | Parent Drug HOMO-LUMO Gap (eV) | Prodrug HOMO-LUMO Gap (eV) | Percent Reduction (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acyclovir | 5.44 | 5.44 | 0 |

| Ganciclovir | 5.42 | 5.14 | 5.17 |

| Torcitabine | 5.28 | 5.25 | 0.57 |

| Cyclopropavir | 4.87 | 4.75 | 2.46 |

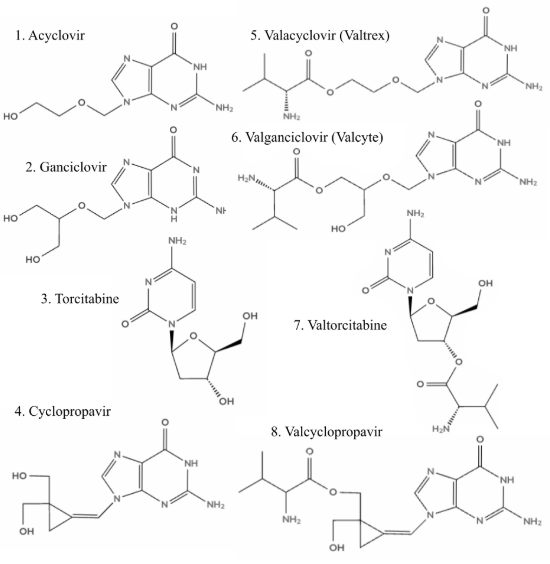

Table 1 shows the HOMO-LUMO gap values for each molecule. A decrease in the magnitude of the HOMO-LUMO gap indicates increased reactivity in the prodrug structure, which can relate to reduced stability. In addition to gap magnitude, the location of a molecule’s HOMO and LUMO can indicate reactive tendencies. Acyclovir and Torcitabine had essentially no change in their HOMO and LUMO’s location when converting into their prodrug forms, centering directly around the pyrimidine structures. By contrast, Ganciclovir and Cyclopropavir’s conversion to prodrug form causes their LUMO to move toward the valine ester, as can be seen in Figure 2. Valganciclovir’s possession of this property causes electrophilic attacks to the valine ester bond, which results in a favorable cleavage of the bond and release of the parent drug. Valcyclopropavir sharing this characteristic with Valganciclovir suggests it would also be able to cleave the valine group when in acidic environments.

Figure 2:Valgancyclovir’s HOMO (red/blue) and LUMO (yellow/green)

Electrostatic Potential Mapping

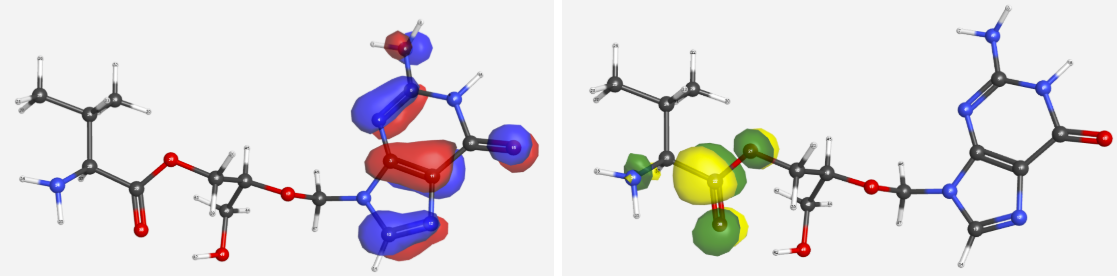

Figure 3:Electrostatic potential visual representation for prodrugs 5-8

Figure 3 shows the electronic charge density maps for prodrugs 5-8. The blue regions of the molecules represent areas with positive charge density, where hydrogens have high affinity for enzymatic binding and are more susceptible to electrophilic attacks. The valine promoiety’s amine group on Valacyclovir, Valganciclovir, and Valtorcitabine have a clear area of high positive charge density, which suggests that they would willingly bind to esterase enzymes. A strong localized negative charge, represented by red regions, around the ester carbonyl carbon is required for binding to the positively charged PepT1 transporter residue. Valtorcitabine having this property indicates it will be able to use this pathway effectively. By contrast, Valcyclopropavir exhibited minimal polarity in its valine charge distribution, likely due to the molecule’s inherently high steric bulk and electrostatic density. This lack of necessary polarity on the valine’s functional groups can prevent necessary protein binding.

ADME Property Calculations

Table 2:Relative charge-masking effect of valine group addition on parent drug hydroxyl group

| Parent Drug | Parent Drug OH Charge | Prodrug OH Charge | Percent Charge Reduction (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acyclovir | -0.758 | -0.556 | 26.65 |

| Ganciclovir | -0.766 | -0.542 | 29.24 |

| Torcitabine | -0.760 | -0.549 | 27.76 |

| Cyclopropavir | -0.730 | -0.570 | 21.92 |

A large contributor to the significant polarity in the parent drugs is their common hanging hydroxyl group, and an effective prodrug would mask some of this polarity to improve pharmacokinetics. In all four prodrug derivatives, the valine group successfully masked 20-30% of the OH group’s polarity (Table 2). The reduction of this charge should increase LogP value and reduce the effective topological polar surface area. However, due to the high polarity of the carbonyl & amine substituents, the valine group did not have this desired effect in a calculation of the entire molecule.

Many drug designers prefer their oral drug candidates to have a LogS in the range of -1 to -3 to optimize water solubility while allowing the drug to permeate intestinal lipid-based membranes. The high LogS of the experimental prodrugs does not hinder absorption due to its distinctive ability to use the PepT1 transport mechanism, but masking the OH group to reduce molecular polarity is still of interest (Table 3). Additionally, an increased number of flexible bonds in a drug improves their ability to conform and bind to key proteins, such as the PepT1 residue and esterase enzymes in this study.

Table 3:Relative change of LogS (at pH 7.4), LogP, and flexibility from the addition of a valine group to parent drugs 1-4

| Parent Drug | Percent Change LogS at pH 7.4 | Percent Change LogP | Percent Change Flexibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acyclovir | +9.92% | -60.58% | +41.65% |

| Ganciclovir | +7.45% | -42.40% | +31.53% |

| Torcitabine | +17.77% | -63.96% | +112.59% |

| Cyclopropavir | +14.41% | -58.81% | +74.95% |

The addition of the valine promoiety had a drastic effect on LogP and molecular flexibility in the prodrug derivatives relative to their parent drug. As can be seen in Table 3, each parent drug experienced an average LogP change of approximately 60%, which correlates to the molecules exhibiting approximately 400% greater nonpolar character. These changes to LogP and LogS could alleviate some of the challenges the parent drug experiences in being absorbed. For example, the extreme polarity of the parent drug can trigger rapid excretion through urination before it can be absorbed into the intestines, and the change in LogP helps slightly with this challenge. Additionally, the change in flexibility should allow the prodrugs to more readily conform and bind to important proteins like the PepT1 protein residue or esterase enzymes.

Structural Stability Predictions

Valtorcitabine and Valcyclopropavir had similarly strong ester bonds to Valacyclovir and Valganciclovir, all having a bond order from 1.020-1.075. This indicates similar resistance to dissociating into the parent drug before the molecule enters the bloodstream. In vivo studies of Valacyclovir conducted by Beutner, 1995 revealed that it does not experience pre-absorption dissociation, and the results of the bond order calculation suggests that this will be the case for Valtorcitabine and Valcyclopropavir as well.

The results of the pKa calculations were largely consistent with the control prodrugs, with the most basic pKa values being almost identical between prodrugs 5-8 at ~7-8. However, while Valacyclovir, Valganciclovir, and Valtorcitabine all had minimum pKa values of 7.5-8.5, Valcyclopropavir’s most acidic pKa value was 3.9. This suggests that in an environment like the intestines, which have a pH of ~6-8, the molecule will completely deprotonate, decreasing its stability and increasing the chance it will undergo base-catalyzed hydrolysis as it passes through.

Protein-Ligand Docking Study

Finally, we conducted a docking study binding Valtorcitabine and Valcyclopropavir to three major protein systems that influence bioavailability: the PepT1/PepT2 solute transporter and the Valacyclovir hydrolase enzyme. Optimally, the experimental prodrugs would have a very high binding affinity to the PepT1/PepT2 proteins, allowing almost all of the drug to enter the bloodstream, but a moderate binding affinity to the Valacyclovir Hydrolase enzyme to allow for moderate release of the parent drug without rapid release from esterase enzymes in the gastrointestinal tract.

Table 4:Prodrug binding affinities (pKi) to PepT1, PepT2, and Valacyclovir Hydrolase protein residues

| Prodrug | PepT1 Binding Affinity | PepT2 Binding Affinity | Valacyclovir Hydrolase |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDB | 7PMW | 9BIS | 2OCI |

| Valacyclovir | 3.5 | 5.4 | 1.7 |

| Valganciclovir | 4.2 | 0.7 | 2.8 |

| Valtorcitabine | 4.1 | 1.5 | 5.1 |

| Valcyclopropavir | 4.7 | 2.0 | 3.0 |

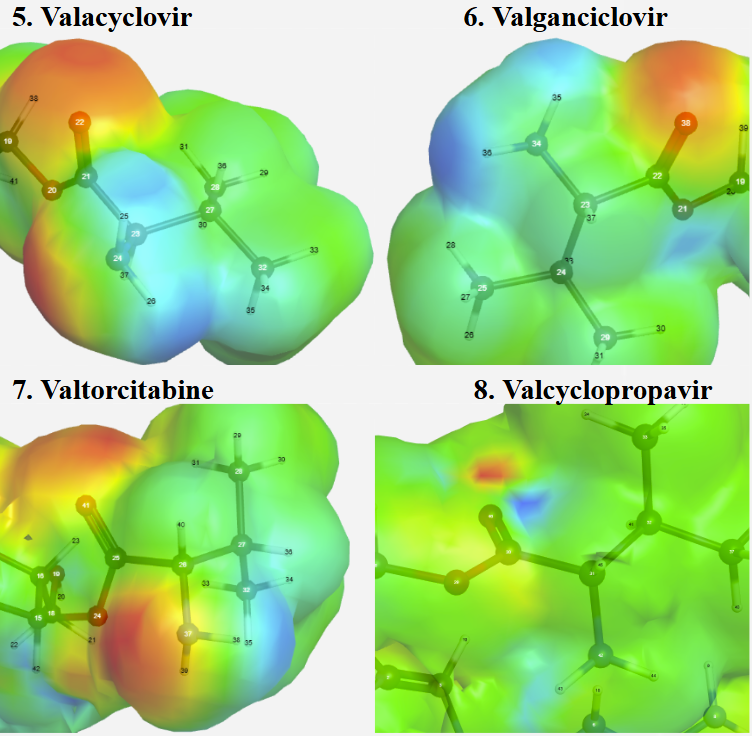

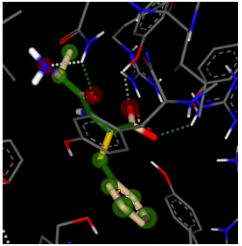

Table 4 contains the binding affinities of prodrugs 5-8 to each binding receptor, expressed as pKi. Valacyclovir was the only molecule capable of effectively binding to the PepT2 transporter protein, with a pKi of 5.4. However, both Valcyclopropavir and Valtorcitabine exhibited favorable binding affinity to the PepT1 transporter at a similar magnitude to Valganciclovir. Valtorcitabine’s docking to PepT1 can be seen in Figure 4, where the valine promoiety’s constituents contribute significantly to the binding interaction. The results suggest that Valtorcitabine and Valcyclopropavir should have a similar ability to Valganciclovir to use the PepT1 active transport mechanism to enter the bloodstream.

Figure 4:Valtorcitabine docked to PepT1 transporter protein

Valacyclovir, Valganciclovir, and Valcyclopropavir all had low to moderate binding affinity to Valacyclovir Hydrolase, having pKi values less than 3. However, Valtorcitabine had a binding affinity of 5.1. Because Valacyclovir Hydrolase is found in small concentrations in the intestines, Valtorcitabine’s binding affinity to the enzyme being 100 times greater than Valganciclovir may cause a large proportion of Valtorcitabine to lose its promoiety before bypassing intestinal membranes, decreasing the concentration of Torcitabine available in the bloodstream. If Valtorcitabine does have high bioavailability, however, it will be a very fast-acting drug due to the increased binding affinity.

Conclusion¶

Relative to Valacyclovir and Valganciclovir, both proven to use the valine prodrug mechanism to reach bioavailabilities greater than 60%, Valcyclopropavir and Valtorcitabine indicated similar capabilities in key measurements of prodrugs, such as stability, reactivity, and ability to penetrate intestinal membranes using a valine promoiety. There were, however, a handful of characteristics that may hold them back from exhibiting similar bioavailabilities in vivo. Valcyclopropavir had a highly distributed LUMO, which could potentially make it more reactive and unstable. Its electrostatic potentials were also very neutral around the valine group, possibly preventing favorable polar enzyme/protein binding. Valcyclopropavir also had a very low minimum pKa value, potentially causing rapid dissociation or excretion in high-pH environments such as the intestines. Valtorcitabine had an abnormally high binding affinity to Valacyclovir Hydrolase, potentially causing premature release of the parent drug before entering the bloodstream. Despite these suboptimal properties, overall our results suggest that the addition of a valine promoiety to Torcitabine and Cyclopropavir will allow the drugs to achieve very high oral bioavailabilities. Valcyclopropavir’s LUMO location will allow for increased stability and effective parent drug release, and Valtorcitabine’s polar electrostatic potentials around the valine group will allow for favorable PepT1 binding. Both prodrugs had stark improvements to their ADME properties, bond strength, stability/acid resistance, and binding affinities, enabling effective usage of the PepT1 oligopeptide transporter mechanism and esterase parent drug release mechanism in similar or improved ranges to Valacyclovir and Valganciclovir. Given their established antiviral potency in vitro against cytomegalovirus and hepatitis B virus, two viruses with highly limited oral treatment options, we believe it would be worthwhile to conduct future in vivo studies of Valtorcitabine and Valcyclopropavir. In doing so, we would hope to verify our prediction that their numerous favorable pharmacokinetic qualities will allow them to reach high oral bioavailability in humans and contribute to the sparse roster of oral antiviral medication.

The author thanks Mr. Robert Gotwals for assistance with this work. Appreciation is also extended to the Burroughs Wellcome Fund and the North Carolina Science, Mathematics and Technology Center for their funding support for the North Carolina High School Computational Chemistry Server.

Copyright © 2024 Gencel. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, which enables reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the creator.

- ADME

- absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion

- B3LYP

- Lee-Yang-Parr correlation functional

- BCS

- Biopharmaceutics Classification System

- CMV

- Cytomegalovirus

- DFT

- Density functional theory

- HBV

- Hepatitis B Virus

- HOMO

- highest occupied molecular orbital

- LUMO

- lowest unoccupied molecular orbital

- NBO

- Natural Bond Orbital

- QSAR

- quantitative structure activity relationship

- Markovic, M., Zur, M., Ragatsky, I., Cvijić, S., & Dahan, A. (2020). BCS Class IV Oral Drugs and Absorption Windows: Regional-Dependent Intestinal Permeability of Furosemide. Pharmaceutics, 12(12), 1175. 10.3390/pharmaceutics12121175

- Vig, B., & Rautio, J. (2011). Amino Acid Prodrugs for Oral Delivery: Challenges and Opportunities. Therapeutic Delivery, 2(8), 959–962. 10.4155/tde.11.75

- Beutner, K. R. (1995). Valacyclovir: a review of its antiviral activity, pharmacokinetic properties, and clinical efficacy. Antiviral Research, 28(4), 281–290. 10.1016/0166-3542(95)00066-6

- PubChem. (n.d.). Ganciclovir. Retrieved April 6, 2025, from https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/substance/46507294

- Umapathy, N. S., Ganapathy, V., & Ganapathy, M. E. (2004). Transport of Amino Acid Esters and the Amino-Acid-Based Prodrug Valganciclovir by the Amino Acid Transporter ATB0,+. Pharmaceutical Research, 21(7), 1303–1310. 10.1023/B:PHAM.0000033019.49737.28

- Demmler-Harrison, G. J. (2009). Congenital cytomegalovirus: Public health action towards awareness, prevention, and treatment. Journal of Clinical Virology, 46, S1–S5. 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.10.007

- Ahmad, J., Ikram, S., Hafeez, A. B., & Durdagi, S. (2020). Physics-driven identification of clinically approved and investigation drugs against human neutrophil serine protease 4 (NSP4): A virtual drug repurposing study. Journal of Molecular Graphics and Modelling, 101, 107744. 10.1016/j.jmgm.2020.107744

- Wu, Z., Drach, J. C., Prichard, M. N., Yanachkova, M., Yanachkov, I., Bowlin, T. L., & Zemlicka, J. (2009). L-Valine Ester of Cyclopropavir: A New Antiviral Prodrug. Antiviral Chemistry and Chemotherapy, 20(1), 37–46. 10.3851/IMP782

- Parr, R. G., Gadre, S. R., & Bartolotti, L. J. (1979). Local density functional theory of atoms and molecules. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 76(6), 2522–2526. 10.1073/pnas.76.6.2522

- Frisch, M. J., Trucks, G. W., Schlegel, H. B., Scuseria, G. E., Robb, M. A., Cheeseman, J. R., Scalmani, G., Barone, V., Petersson, G. A., Nakatsuji, H., Li, X., Caricato, M., Marenich, A. V., Bloino, J., Janesko, B. G., Gomperts, R., Mennucci, B., Hratchian, H. P., Ortiz, J. V., … Fox, D. J. (2016). Gaussian˜16 Revision C.01.

- North Carolina High School Computational Chemistry Server. (n.d.). Retrieved April 6, 2025, from http://chemistry.ncssm.edu/

- B., F. R., Prasana, J. C., Muthu, S., & Abraham, C. S. (2019). Molecular docking studies, charge transfer excitation and wave function analyses (ESP, ELF, LOL) on valacyclovir : A potential antiviral drug. Computational Biology and Chemistry, 78, 9–17. 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2018.11.014

- Besnard, J., Ruda, G. F., Setola, V., Abecassis, K., Rodriguiz, R. M., Huang, X.-P., Norval, S., Sassano, M. F., Shin, A. I., Webster, L. A., Simeons, F. R. C., Stojanovski, L., Prat, A., Seidah, N. G., Constam, D. B., Bickerton, G. R., Read, K. D., Wetsel, W. C., Gilbert, I. H., … Hopkins, A. L. (2012). Automated design of ligands to polypharmacological profiles. Nature, 492(7428), 215–220. 10.1038/nature11691

- Lai, L., Xu, Z., Zhou, J., Lee, K.-D., & Amidon, G. L. (2008). Molecular Basis of Prodrug Activation by Human Valacyclovirase, an α-Amino Acid Ester Hydrolase. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 283(14), 9318–9327. 10.1074/jbc.M709530200

- Parker, J. L., Deme, J. C., Lichtinger, S. M., Kuteyi, G., Biggin, P. C., Lea, S. M., & Newstead, S. (2024). Structural basis for antibiotic transport and inhibition in PepT2. Nature Communications, 15(1), 8755. 10.1038/s41467-024-53096-6