Risk Factors of Frequent Poor Mental Health Days Among Adults in the United States

Abstract¶

Mental health has become a prominent public health issue in the United States. As such, understanding the risk factors for any condition affecting mental well-being is an important undertaking. This study analyzed the 2022 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey to determine the relationship between frequent poor mental health (FPMH) and several demographic, behavior, and quality of life factors among adults in the United States. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines FPMH as 14 or more poor mental health days in the past 30 days. Weighted cross-tabulation and multivariate logistic regression were used to find the factors associated most strongly with FPMH. Overall, about 15% of American adults had FPMH. There were significant disparities in the prevalence of FPMH based on demographics, notably among adults with annual incomes below $15,000 (29.43%) and adults unable to work (38.12%). Additionally, current smokers were 1.55 times more likely to report FPMH than non-smokers; this number rose to 4.20 when adults managing 6-8 chronic conditions were compared to adults managing 0 conditions. These findings highlight the importance of targeted mental health interventions, providing a blueprint for future support.

Introduction¶

Mental health has become an increasingly prominent public health issue in the United States. Frequent poor mental health (FPMH), which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines as 14 or more days of poor mental health in the past month Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2023, affects a significant portion of the adult population, resulting in significant disturbances to an individual’s quality of life. Previous research has identified links between demographic factors and mental health outcomes Miyakado-Steger & Seidel, 2019, but there is little comprehensive analysis that incorporates behavioral risk factors and quality of life indicators for the broader patient population that is adults in the United States Pierannunzi et al., 2013. This paper intends to fill this gap by implementing three categories (levels) of potential risk in relation to FPMH: demographic, behavioral, and quality of life.

A demographic factor is a widely accepted characteristic used to classify or analyze specific patient populations. Some common examples include age, gender, and income bracket. Analysis through this lens is useful because it provides a measure of the inherent societal imbalances (in relation to mental health) within the United States. However, these characteristics are relatively static in the short term. Results can guide targeted intervention but do not offer the patient a solution. As such, behavioral factors are also important.

A behavioral factor refers to the effect of a patient’s actions on their health. Some lifestyle choices, such as smoking or binge drinking, negatively impact a patient’s overall well-being. Others, such as daily physical exercise, have a positive effect. In contrast to demographic factors, one has a greater degree of control over these characteristics of one’s life. This section of analysis provides more actionable results for the individual patient.

Finally, some factors do not refer to specific patient populations or behaviors. Generally, these refer to a patient’s “quality of life”. For example, if a patient manages multiple chronic conditions, this reduced quality of life may have effects that extend beyond physical well-being. Accounting for this type of factor allows for a model more sensitive to the connection between physical and mental health.

Every year, the CDC performs the Behavior Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). This is a nationwide telephone survey intended to gather information about the United States adult population for public health purposes. The survey records the respondent’s demographics, screens for risky behaviors, and asks quality of life questions. Through the CDC’s extensive outreach and weighting strategies, the results of this survey can be generalized to the greater United States adult population Liu et al., 2018. As such, this paper refers to the respondent pool when referencing raw (unweighted) data, and to the United States adult population when discussing the weighted data.

This paper utilizes 2022 BRFSS data (the latest year available at the time of analysis) to determine the prevalence of demographic, risk, and quality of life factors among adults aged 18 or older in the United States in relation to FPMH. The survey, using both landline and cellphone outreach, garnered 445,132 responses from all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the US Virgin Islands Liu et al., 2018. For the remainder of this paper, “states” will be used as a blanket term for any region that participates in the BRFSS.

The BRFSS includes 3 parts: a core component, optional modules, and state-added questions Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2023. All states use the core component, which allows for a standardized view of public health in the United States. The optional modules ask about more specific topics. A state particularly worried about one of these topics may elect to include the necessary module in its BRFSS. If a state desires more targeted information not asked by the CDC, it may develop the required questions individually and add them solely to its state-specific section of BRFSS Liu et al., 2018.

Methods¶

Enviroment and Packages¶

This analysis was performed with the R programming language (version 4.4.1) and run in the RStudio environment. The following libraries were used:

- survey (version 4.4-2): This package provides the tools necessary to handle weighted survey data, stratified sampling, and clustering sampling.

- dplyr (version 1.1.4): This package allows for data manipulation through recoding and filtering nonresponse values.

- openxlsx (version 4.2.7.1): This package reads, writes, and manipulates an Excel workbook to better format the analysis results.

Weighting, Stratification, and Clustering¶

The CDC performs extensive stratification, weighting, and clustering to ensure that the results from the survey can be generalized to the greater population Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2023. Weighting corrects for biases due to unequal coverage or nonrandom high nonresponse rates. By selectively altering the significance of each datapoint, the BRFSS results better reflect the demographics of the United States population. Stratification also improves representativeness by dividing the population into subgroups (strata) based on geographic area and density of phone numbers Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2023. Each stratum is sampled from separately, ensuring that each region is represented correctly. Finally, clustering simplifies the sampling process by dividing the population into primary sampling units (PSUs). These sampling units are then chosen at random for data collection Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2023.

This study considers the core-only section of the 2022 BRFSS. Optional or state-specific modules were not included. Responses to those modules cannot represent the condition of the greater United States population, as there are inherent differences in the information gleaned from each question. To weight the variables in solely the core section, the CDC includes the _LLCPWT variable. Similarly, _STSTR is used for stratification, and _PSU applies the necessary clustering. These methods are passed through the survey design object in R.

Recording and Nonresponse Filtration¶

When someone participates in the survey, they can provide one of two response types for a given question. The first is an uninformative response: they elect not to respond or don’t know the answer. The second is informative. It can be an affirmative or negative, the option that matches their behavior or demographic, or the number of days or diseases that best fit their condition. All these potential responses are coded as a different number, which is indicated by the corresponding BRFSS Codebook for 2022 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2023.

If a question elicits an affirmative or negative response, as is the case with “During the past month, other than your regular job, did you participate in any physical activities or exercises such as running, calisthenics, golf, gardening, or walking for exercise?”, it is simple to code the potential responses:

- Yes = 1

- No = 2

- Don’t know / Not sure = 7

- Refusal to answer = 9

For questions where respondents select the best matching option from multiple choices (like behavioral tendencies or demographics), the coding varies by question due to the range of possible responses. For example, consider the question which determines current employment:

“Are you currently… ?”¶

- Employed for wages = 1

- Self-employed = 2

- Out of work for 1 year or more = 3

- Out of work for less than 1 year = 4

- A Homemaker = 5

- A Student = 6

- Retired = 7

- Unable to work = 8

- Refused = 9

Finally, questions for which responses are provided by selecting a number of days or conditions are coded based on the number provided by the respondent. Further distinctions can be manually recoded once the data is downloaded from the CDC. Consider the following question:

“Now thinking about your mental health, which includes stress, depression, and problems with emotions, for how many days during the past 30 days was your mental health not good?”¶

- Number of days = _ _ (01-30)

- None = 88

- Don’t know / Not sure = 77

- Refused = 99

Note that the “catch-all” (None, Don’t know / Not sure, Refused) codes have been multiplied by 11 because it is possible for the respondent to report 7, 8, or 9 days of poor mental health in the past month. This removes ambiguity regarding the significance of a particular code. This is done any time there is a possibility of an overlap between an informative response and a catch-all code Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2023.

The CDC recodes responses to make analysis more straightforward. For yes/no and categorical questions, it simplifies the levels and groups all missing responses under code 9 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2023. For numerical responses (like number of days or conditions), it creates standardized levels. These recoding procedures help streamline data analysis. Variables recoded by the CDC are preceded with an underscore (_).

All responses containing 7/9 and 77/99 codes in the analyzed variables were removed to prevent these non-substantive responses from artificially skewing the statistical calculations.

The following were used as predictor (independent) variables for this analysis. Manual recodes are noted where applied. If a variable was renamed for this analysis, this is indicated by an arrow next to the original variable name.

_SEX

- Male = 1

- Female = 2

_AGE_G

- Age 18 to 24 = 1

- Age 25 to 34 = 2

- Age 35 to 44 = 3

- Age 45 to 54 = 4

- Age 55 to 64 = 5

- Age 65 or older = 6

_RACEPR1

- White only, non-Hispanic = 1

- Black only, non-Hispanic = 2

- American Indian or Alaskan Native only, non-Hispanic = 3

- Asian only, non-Hispanic = 4

- Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander only, non-Hispanic = 5

- Multiracial, non-Hispanic = 6

- Hispanic = 7

_EDUCAG _educag_

- Did not graduate High School = 1

- Graduated High School = 2

- Attended College or Technical School = 3

- Graduated from College or Technical School = 4

MARITAL _marital_

- Married = 1

- Divorced = 2

- Widowed = 3

- Separated = 4

- Never married = 5

- A member of an unmarried couple = 6

EMPLOY1 _employ1_

- Employed for wages = 1

- Self-employed = 2

- Out of work for 1 year or more = 3

- Out of work for less than 1 year = 4

- A Homemaker = 5

- A Student = 6

- Retired = 7

- Unable to work = 8

_INCOMG1 _income3_

- Less than $15,000 = 1

- 25,000 = 2

- 35,000 = 3

- 50,000 = 4

- 100,000 = 5

- 200,000 = 6

- $200,000 or more = 7

VETERAN3 _veteran3_

- Yes = 1

- No = 2

_CHLDCNT _CHLDCNT_

- No children in household = 1

- One child in household = 2

- Two children in household = 3

- Three children in household = 4

- Four children in household = 5

- Five or more children in household = 6

_TOTINDA _TOTINDA_

- Had physical activity or exercise = 1

- No physical activity or exercise in the last 30 days = 2

_RFSMOK3 _RFSMOK3_

- No = 1

- Yes = 2

_RFBING6 _RFBING6_

- No = 1

- Yes = 2

DIABETES4, _MICHD, CVDSTRK3, _LTASTH1, _DRDXAR2, CHCSCNC1, CHCOCNC1, CHCCOPD3, CHCKDNY2 chronic_disease

- Manages no chronic conditions = 1

- Manages 1-2 chronic conditions = 2

- Manages 3-5 chronic conditions = 3

- Manages 6-8 chronic conditions = 4

This variable was recoded. First, the existence of each chronic condition (diabetes, cancer, asthma, arthritis, chronic kidney disease, stroke, coronary heart disease, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) was recorded. Respondents were then grouped by the number of conditions they managed, as indicated above.

The following was used as the outcome (dependent) variable. The 14-day cutoff is based on the CDC’s recommendation for classifying a respondent’s mental health as frequently poor Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2023.

_MENT14D _ment14_

- Less than 14 days of poor mental health in the last 30 days (“satisfactory”) = 0

- 14 or more poor mental health days in the last 30 days (“frequent, poor”) = 1

This variable was manually recoded to create a binary outcome, which is necessary to perform logistic regression analysis.

Cross-tabulation for Column Percentages¶

Once the variables were recoded, original frequency counts were found for each cross tabulation between all predictor variable levels and the two outcome variable levels. Then, a weighted count for each cross-tabulation was generated (based on the CDC’s survey design weighting, stratification, and clustering). This allows the number to more accurately represent the true number of United States adults who fit a given cross-tabulation (give or take the standard error upon weighting, which is also included). Column percentages were calculated by taking the weighted number of people with FPMH in each level and dividing by the weighted total number of people in the same level. For example, the column percentage for adult women in the United States with frequent poor mental health was found by dividing that weighted frequency by the estimated total number of adult women in the United States (also a weighted frequency count). 95% confidence intervals were then found for each column percentage based on the standard errors of the respective weighted frequencies.

Rao-Scott chi-squared tests were performed on weighted frequency counts for each cross tabulation. This allows one to determine whether the distribution of adults reporting FPMH differed by cross-tabulation. The Rao-Scott chi-squared test was chosen because these frequency counts are weighted. A standard Pearson chi-squared test cannot account for the effect of weighting, stratification, and clustering Rao & Scott, 1981. Significance was set at a p-value < 0.01.

Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis¶

A multivariate logistic regression model was built based on the recoded variables. This was used to assess the variation each factor had on FPHM. The logistic regression provides the multiplicative change in odds that _ment14_ = 1 for each one-unit increase in a given predictor variable, while holding all other variables constant Sperandei, 2014.

For each variable, one level was chosen as the reference category. For a clearer comparison, the level expected to have the lowest prevalence of FPMH was set for reference. These are indicated below for each predictor variable:

- _SEX: Male (1)

- _AGE_G: Age 18 to 24 (1)

- _RACEPR1: White only, non-Hispanic (1)

- _educag_: Graduated from College or Technical School (4)

- _marital_: Married (1)

- _employ1_: Employed for wages (1)

- _income3_: $200,000 or more (7)

- _veteran3_: No (2)

- _CHLDCNT_: No children in household (1)

- _TOTINDA_: Had physical activity or exercise (1)

- _RFSMOK3_: No (1)

- _RFBING6_: No (1)

- chronic_disease: Manages no chronic conditions (1)

The desired logistic regression returns coefficients (β) which represent the log odds for each predictor variable level compared to its reference level (both in relation to an individual’s likelihood of developing FPMH). Each log odd is then transformed into an odds ratio by calculating (raising e to the power of each log odd) Sperandei, 2014. A significant odds ratio is a valuable tool to compare the effects of each level on the outcome variable. This value indicates how much more or less likely an individual in a specific level is to report FPMH compared to the reference level, while holding the other predictor variables constant. The significance of each odds ratio was determined by the 95% confidence interval. If the interval included 1, the odds ratio was deemed insignificant Sperandei, 2014.

Results¶

The following tables provide the cross-tabulation results from the most significant predictor variables.

| RS 2 p < .0001 | Did not graduate High School | Graduated High School | Attended College/Technical School | Graduated College/Technical School |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <14 days of FPMH | ||||

| Column Percentage | 80.04% | 82.29% | 82.67% | 89.04% |

| Column Percentage 95% CI | 79.06% -80.99% | 81.82% - 82.75% | 82.24% - 83.09% | 88.75% - 89.33% |

| ≥14 days of FPMH | ||||

| Column Percentage | 19.96% | 17.71% | 17.33% | 10.96% |

| Column Percentage 95% CI | 19.01% - 20.94% | 17.25% - 18.18% | 16.91% - 17.76% | 10.67% - 11.25% |

| Total | ||||

| Weighted Frequency | 29266273 | 70592764 | 77912720 | 79203973 |

Table 1: FPMH by Education

| RS 2 p < .0001 | Employed for wages | Self -employed | Out of work ≥ 1 yr | Out of work < 1 yr | Home - maker | Student | Retired | Unable to work |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <14 days of FPMH | ||||||||

| Column Percentage | 85.55% | 87.88% | 72.97% | 70.46% | 86.04% | 75.56% | 90.96% | 61.88% |

| Column Percentage 95% CI | 85.23% - 85.86% | 87.16% - 88.57% | 71.08% - 74.79% | 68.46% - 72.39% | 84.84% - 87.16% | 74.07% - 76.99% | 90.59% - 91.33% | 60.66% - 63.08% |

| ≥14 days of FPMH | ||||||||

| Column Percentage | 14.45% | 12.12% | 27.03% | 29.54% | 13.96% | 24.44% | 9.03% | 38.12% |

| Column Percentage 95% CI | 14.14% - 14.77% | 11.43% - 12.84% | 25.21% - 28.92% | 27.61% - 31.54% | 12.84% - 15.16% | 23.01% - 25.93% | 8.67% - 9.41% | 36.92% - 39.34% |

| Total | ||||||||

| Weighted Frequency | 120779738 | 24004358 | 6394978 | 6501600 | 12513220 | 12168959 | 51715285 | 15868736 |

Table 2: FPMH by Employment Status

| RS 2 p<.0001 | <$15,000 | $15,000 - <$25,000 | $25,000 - <$35,000 | $35,000 - <$50,000 | $50,000 -<$100,000 | $100,000 - <$200,000 | ≥$200,000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <14 days of FPMH | |||||||

| Column Percentage | 70.57% | 77.50% | 79.70% | 82.94% | 85.75% | 89.44% | 92.06% |

| Column Percentage 95% CI | 69.27% - 71.83% | 76.58% - 78.39% | 78.85% - 80.52% | 82.20% - 83.66% | 85.30% - 86.20% | 88.93% - 89.92% | 91.35% - 92.72% |

| ≥14 days of FPMH | |||||||

| Column Percentage | 29.43% | 22.50% | 20.30% | 17.06% | 14.25% | 10.56% | 7.94% |

| Column Percentage 95% CI | 28.17% - 30.73% | 21.61% - 23.42% | 19.48% - 21.15% | 16.34% - 17.80% | 13.80% - 14.70% | 10.08% - 11.07% | 7.28% - 8.65% |

| Total | |||||||

| Weighted Frequency | 13236673 | 20217159 | 24663916 | 25475921 | 57235233 | 41762275 | 15434731 |

Table 3: FPMH by Income Level

| RS 2 p = .0002 | A Veteran | Not a Veteran |

|---|---|---|

| <14 days of FPMH | ||

| Column Percentage | 85.56% | 84.08% |

| Column Percentage 95% CI | 84.85% - 86.25% | 83.84% - 84.33% |

| ≥14 days of FPMH | ||

| Column Percentage | 14.44% | 15.92% |

| Column Percentage 95% CI | 13.75% - 15.15% | 15.67% - 16.16% |

| Total | ||

| Weighted Frequency | 25351175 | 228681952 |

Table 4: FPMH by Veteran Status

| RS 2 p < .0001 | Had physical activity | Did not have physical activity |

|---|---|---|

| <14 days of FPMH | ||

| Column Percentage | 85.99% | 78.66% |

| Column Percentage 95% CI | 85.73% - 86.24% | 78.14% - 79.18% |

| ≥14 days of FPMH | ||

| Column Percentage | 14.01% | 21.34% |

| Column Percentage 95% CI | 13.76% - 14.27% | 20.82% - 21.86% |

| Total | ||

| Weighted Frequency | 196628045 | 61155165 |

Table 5: FPMH by Participation in Physical Activity

| RS 2 p < .0001 | Current Smoker | Not a Current Smoker |

|---|---|---|

| <14 days of FPMH | ||

| Column Percentage | 72.59% | 85.70% |

| Column Percentage 95% CI | 84.62% - 85.15% | 79.57% - 80.84% |

| ≥14 days of FPMH | ||

| Column Percentage | 27.41% | 14.30% |

| Column Percentage 95% CI | 14.85% - 15.38% | 19.16% - 20.43% |

| Total | ||

| Weighted Frequency | 29959928 | 204459603 |

Table 6: FPMH by Current Smoking Status

Figure 1:FPMH by Smoking Status

27.41% of smokers had FPMH while 14.30% of non-smokers had FPMH. The national average was 15%.

| RS 2 p < .0001 | 0 Chronic Conditions | 1-2 Chronic Conditions | 3-5 Chronic Conditions | 6-8 Chronic Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <14 days of FPMH | ||||

| Column Percentage | 87.15% | 82.93% | 74.57% | 59.48% |

| Column Percentage 95% CI | 86.84% - 87.45% | 82.56% - 83.29% | 73.68% - 75.44% | 53.66% - 65.04% |

| ≥14 days of FPMH | ||||

| Column Percentage | 12.85% | 17.07% | 25.43% | 40.52% |

| Column Percentage 95% CI | 12.55% - 13.16% | 16.71% - 17.44% | 24.56% - 26.32% | 34.96% - 46.34% |

| Total | ||||

| Weighted Frequency | 132091777 | 102192756 | 22955304 | 1056305 |

Table 7: FPMH by Number of Chronic Conditions

Figure 2:FPMH by Number of Chronic Conditions

40.52% of people with 6-8 chronic conditions had FPMH while 12.85% of people with 0 chronic conditions, 17.07% of people with 1-2 chronic conditions, and 25.43% of people with 3-5 chronic conditions had FPMH. The national average was 15%.

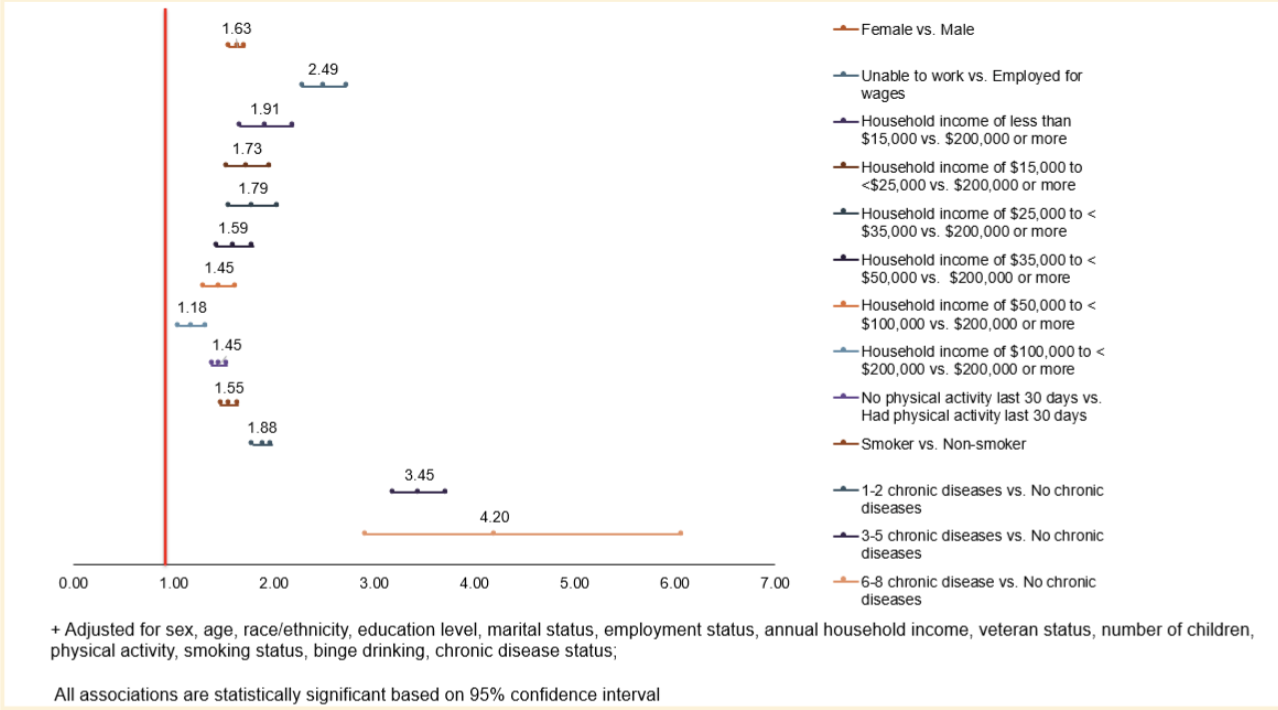

The following figure highlights the most significant odds ratios and their 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 3:Significant odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals

Most Significant Results¶

This analysis supports the characterization of poor mental health as a prominent public health issue, as 15% of American adults met the criteria to be considered as having FPMH. Based on the demographic factors, females (18.33%), those aged 18 to 24 (25.11%), multiracial non-Hispanics (24.44%), those unable to work (38.12%), and those making less than $15,000 annually (29.43%) had the highest prevalence of FPMH (p-value < .0001 for all).

Behavioral and quality of life factors also significantly affected an individual’s likelihood of having FPMH, as those who completed no physical activity in the last 30 days (21.34%), current smokers (27.41%), those who engaged in binge drinking in the last 30 days (19.78%), and those who managed chronic diseases (17.07% - 40.52%) also experienced a higher prevalence of FPMH than the national average (p-value <.0001 for all).

The multivariate model revealed more about the demographic, behavioral, and quality of life factors associated most strongly with FPMH. Notably, adults unable to work were 2.49 (95% CI: 2.28 – 2.72) times more likely to report FPMH than adults employed for wages. FPMH prevalence increased as the income bracket decreased: FPMH was 1.91 (95% CI: 1.66 – 2.19) times more likely for adults in households earning less than $15,000 than those in households earning $200,000 or more. Smoking posed the highest behavioral risk of FPMH, as current smokers were 1.55 (95% CI: 1.46 - 1.64) times more likely to have FPMH than non-smokers. Similarly, those who lacked physical activity were 1.45 (95% CI: 1.38 – 1.53) times more likely to have FPMH than those who exercised in the last month. Finally, the prevalence of FPMH increased with an individual’s number of chronic diseases. Adults managing 6-8 chronic diseases were 4.20 (95% CI: 2.91 – 6.06) times more likely to meet criteria for FPMH than those managing no chronic diseases.

Implications¶

These results suggest that there is a significant income-based disparity among adults affected by FPMH in the United States. Many treatments such as therapy and medication are not readily accessible to lower-income households. This finding highlights the need for expanded support programs that provide mental health resources for those struggling financially, such as increased funding for community mental health centers and more flexible payment options. Physical activity, an accessible method of managing mental health, also requires enhanced promotion. Finally, work is needed to integrate the mental health needs of physically vulnerable patients into their care strategies. These patients require support for both managing chronic conditions and the associated mental stress.

Limitations¶

There are a few primary limitations of this study. Most significantly, this is a cross-sectional analysis, meaning that it is taken from a single point in time. As such, the findings indicate significant correlation between the predictor variables and FPMH but cannot establish causation. As the analysis was performed on survey data, one cannot determine the direction of effect for the predictor variables and an individual’s likelihood of having FPMH. For example, if a respondent who was a current smoker reported FPMH, one cannot know if smoking caused FPMH, or if FPMH resulted in smoking as a coping strategy. Additionally, while the multivariate logistic regression analysis controls for each demographic, behavior, and quality of life factor in the study, it cannot account for any confounding variables not captured by the BRFSS. Some examples include family history of mental health conditions and existence of social support networks.

Furthermore, while not an arbitrary categorization, respondents who experienced some poor mental health days but not 14 or more still need support. Further splitting of the outcome variable levels is necessary for a more nuanced analysis. Similarly, grouping effect of chronic conditions solely by number (disregarding which each condition is) muddies the conclusions that can be drawn about quality of life factors. A more specific categorization would result in a more actionable analysis.

Finally, the only other reference to mental health in the 2022 BRFSS questionnaire was: “Do you have a depressive disorder (including depression, major depression, dysthymia, or minor depression)?” However, existence of depression was not chosen as a predictor variable because of its inherent strong association with FPMH. Existence of depression would predict FPMH very well, causing inflated standard errors and unreliable coefficient estimates. Thus, the model becomes unstable, making it difficult to assess the correlation between the other predictor variables and FPMH.

Future Direction¶

A future direction for this project is to run another analysis in which existence of depression is the outcome variable and compare the difference in results. This illuminates the disparity among which patients can obtain a diagnosis of depression out of those who experience FPMH, guiding future supplemental mental health support.

Data Availability Statement¶

The deidentified data and code that support the findings of this study are openly available in the following GitHub repository: https://

Copyright © 2024 Chintapalli. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, which enables reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the creator.

- BRFSS

- Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

- CDC

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention

- FPMH

- Frequent Poor Mental Health

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). LLCP 2022 Codebook Report. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/2022/zip/codebook22_llcp-v2-508.zip

- Miyakado-Steger, H., & Seidel, S. (2019). Using the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System to Assess Mental Health, Travis County, Texas, 2011–2016. Preventing Chronic Disease, 16, 180449. 10.5888/pcd16.180449

- Pierannunzi, C., Hu, S. S., & Balluz, L. (2013). A systematic review of publications assessing reliability and validity of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), 2004–2011. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), 49. 10.1186/1471-2288-13-49

- Liu, J., Jiang, N., Fan, A. Z., & Weissman, R. (2018). Alternatives in Assessing Mental Healthcare Disparities Using the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Health Equity, 2(1), 199–206. 10.1089/heq.2017.0056

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Weighting the Data. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/2022/pdf/2022-Weighting-Description-508.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Calculated Variables in the 2022 Data File of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/2022/pdf/2022-calculated-variables-version4-508.pdf

- Rao, J. N. K., & Scott, A. J. (1981). The Analysis of Categorical Data from Complex Sample Surveys: Chi-Squared Tests for Goodness of Fit and Independence in Two-Way Tables. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 76(374), 221–230. 10.1080/01621459.1981.10477633

- Sperandei, S. (2014). Understanding logistic regression analysis. Biochemia Medica, 12–18. 10.11613/BM.2014.003