Computationally Modeling Factors of Aging that Affect the Population of T-cells and B-cells of Humans Age 60 and Older

Abstract¶

The study of T-cell and B-cell population dynamics concerning the effects of aging presents significant challenges due to various factors. Individual variations in health conditions and the complex interrelations within the immune system can lead to diverse outcomes. To address these complexities, we implemented a systematic approach to create computational models, which simulate the long-term population dynamics of T-cells and B-cells under conditions of aging. These models encompass essential physiological processes, including thymic output, bone marrow production, cellular activation, senescence, and natural cell death. Additionally, we generated graphical representations from the models to facilitate a clearer visualization of the observed trends. Age 60 was selected as the initial point for this analysis, as the effects of the aging immune system become increasingly evident at this stage, making previous facts by other studies more recognizable. This study underscores the potential of computational modeling capabilities in advancing our comprehension of the immune system, providing valuable insights for tracking and visualizing population dynamics. The modeling done here can be added upon to reach higher complexities to models that can accurately reflect what occurs in real life.

Introduction¶

Aging is an inevitable process characterized by a gradual decline in the human body’s functionality, including the immune system’s efficiency. While some mechanisms of aging are well-documented, such as thymic involution, the specific factors underlying these processes are not yet fully understood. As individuals age, the responsiveness of T-cells and B-cells to pathogens decreases, and there is also an increased risk of autoimmune complications. No table alterations in the immune system typically commence around the age of 60 Weyand & Goronzy, 2016. It is essential to clarify that both T-cells and B-cells are produced in the bone marrow; however, T-cells migrate to the thymus to undergo maturation, enabling them to effectively combat pathogens. This research emphasizes computational modeling to study the effects of aging on the behavior, dynamics, and interactions of T-cell and B-cell populations, which contribute to the overall decline of the immune system.

The thymus gland is responsible for generating naive T-cells, which are crucial for activating the immune response. This maturation process is meant to prevent and eliminate self reactive T-cells in the body. Thymic involution, the process by which the thymus gland progressively shrinks, begins as one is born and continues throughout an individual’s life Thymic involution, 2025. In younger individuals, this involution occurs at a gradual rate, allowing for efficient regeneration of thymic cells and maintaining a robust population of naive T-cells. However, this process poses significant challenges as individuals reach approximately 60 years of age, at which point the rate of cell regeneration decreases markedly. Consequently, there is a pronounced decline in the population of naive T-cells over subsequent years, which adversely affects the immune response to pathogens and increases the susceptibility to autoimmune complicationsThymic involution, 2025. It is important to note that the rate of thymic involution varies widely among individuals, influenced by factors such as lifestyle, genetics, and gender. Furthermore, with our advancement in healthcare, people can seek thymus therapy which regenerates thymus cells to increase naive T-cell count. Therefore, developing a universal model applicable to all individuals is complex. This study will account for thymic involution in the modeling of T-cell populations, but it’s worth noting that its rate may vary among individuals and will not reflect possible therapy interventions.

The bone marrow plays a crucial role in the production of both B-cells and T-cells; however, it primarily serves as the site for B-cell maturation. The maturation process occurring within the bone marrow resembles that of the thymus, wherein self-reactive B-cells are identified and eliminated. As individuals age, the bone marrow undergoes deterioration, leading to decreased cellularity and a corresponding reduction in the production of naive B-cells Reitman, n.d.. This decline becomes increasingly evident around the age of 60 and older. Activated B-cells, which possess the capacity to generate billions of antibodies, tend to reach a state of exhaustion slightly more rapidly than T-cells. This phenomenon is attributable to the considerable amount of energy and resources expended at the cellular level. Furthermore, the aging process exacerbates this exhaustion, resulting in diminished antibody production and a heightened likelihood of B-cells entering a state of senescence. Senescence is the aging of cells, rendering them dysfunctional, long-lasting, and space-occupying. Similar to the thymus, the rate of bone marrow deterioration varies among individuals, influenced by a variety of factors. Bone marrow transplantation represents one of the most effective, albeit challenging, methods for regenerating bone marrow; this procedure is generally more complex than thymus therapy. Such variability complicates the endeavor to accurately model bone marrow function across diverse individuals. This study will incorporate considerations of bone marrow deterioration into the modeling of B-cell populations; however, it will not reflect the individual differences in deterioration rates or account for the potential effects of bone marrow transplants.

The rates in the research were chosen to help reflect that of a 60-year-old’s immune system. Some rates considered in this paper are death rate, activation rate, and senescence rate. Additionally, age accelerates the senescence rate of all populations and declines the activation rate weakening the immune response. Each population and cell type will present different rates.

Activation in the immune system resembles a domino effect. Age does affect the rate at which T-cells and B-cells are activated, and as stated before the rates of these decline over time which weakens the immune response (aligns with the fact that older people have weaker immune systems). For example, helper T-cells are often seen as the activator for B-cells B cell, 2025 but that rate decreases as the population of naive T-cells decreases. On the other hand, the senescence rate will accelerate over time leading to a more dominant population of senescent cells seen later in the older ages.

The frequencies of death and senescence of naive T-cells and B-cells are lower than those observed in other immune cell populations. These naive cells are not subject to exhaustion or prolonged activation resulting from combating infections, which contributes to their low turnover rates concerning death and senescence. Naive has selective signaling T-cells engage via their IL-7R receptors [noauthor_t_2025], while naive B-cells utilize BAFF receptors B cell, 2025 and both promote cellular survival and inhibit premature apoptosis, provided they do not encounter an activating antigen. In contrast, the activated cell population exhibits the highest turnover rates for both death and senescence. This phenomenon arises from their constant activity, which involves the production of significant quantities of cytokines that deplete their energy and resources, ultimately leading to exhaustion. Consequently, these activated cells may undergo apoptosis or become senescent. This state of exhaustion is increasingly prevalent in older human immune systems, resulting in elevated rates of death and senescence within this population. Memory cells represent a specialized subset of activated cells that retain the capacity to recognize and respond to previously encountered pathogens. Given their lower activity levels and reduced cytokines production compared to activated cells, memory cells exhibit a diminished death rate and can persist in the body for extended periods. Nonetheless, they are not entirely immune to exhaustion, which may result in low levels of senescence turnover. Senescent cells are characterized by a loss of functionality and an inability to replicate, yet they tend to persist over time. Various factors, including cellular exhaustion, DNA damage, and chronic inflammation—each of which is associated with the aging process—can induce their formation Weyand & Goronzy, 2016. These senescent cells accumulate within the body and may compromise immune responses as well as the efficacy of vaccinations A primary reason for their prolonged existence is their inherent resistance to apoptosis [noauthor_senescent_2021]. However, senescent cells remain unstable and unpredictable, as numerous factors may influence the senescence process. Consequently, it is increasingly common to observe a substantial rise in senescent cells among the elderly, leading to their eventual dominance over other immune cell populations. The modeling process will take into account most of these facts, except a few like inflammation, and produce a quantitative reflection.

Computational Approach¶

In order to effectively model population dynamics, differential equations are particularly utilized for representing the changes within biological populations. This study will formulate and utilize the sets of equations to reflect the dynamics of both T-cells and B-cells. Specifically, we will focus on four distinct populations: naive, activated, memory, and senescent cells. The analysis will cover a 50-year period, beginning at age 60 and continuing until age 110.

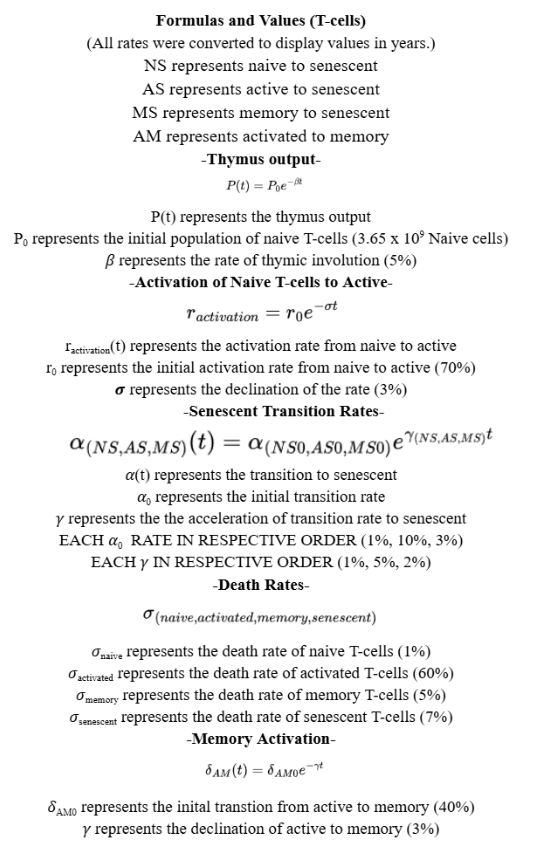

This model will operate under the following assumptions: chronic inflammation is absent, no regenerative procedures have been conducted on the thymus or bone marrow, all types of activated cells are grouped into one active population, all types of memory cells are grouped into one memory population, and the model initiates with no activated adaptive immune cells. Furthermore, there exists a relatively low quantity of naive cells, coupled with a presence of memory and senescent cells, as a result of a slightly compromised immune system, and the rates incorporated in the model will aid in reflecting these specified conditions. ChatGPT was used to help develop differential equations, sub-formulas (Fig. 1), and rate parameters that describe the population dynamics of different T-cell subsets.

Equation (1) represents the dynamics of naive T cells, while Equation (2) represents the dynamics of activated T-cells. Additionally, Equation (3) represents the population dynamics of memory T-cells, and Equation (4) represents the dynamics of senescent T-cells. All rates are expressed in terms of years. ChatGPT offered reasonable rates for constructing the model, which reflects a moderately compromised immune system. Although the relationship is nonlinear and does not precisely adhere to an exponential form, exponential functions were selected as the most suitable approach for modeling these dynamics ChatGPT, n.d..

Figure 1:Rates and sub-formulas of T-cell population

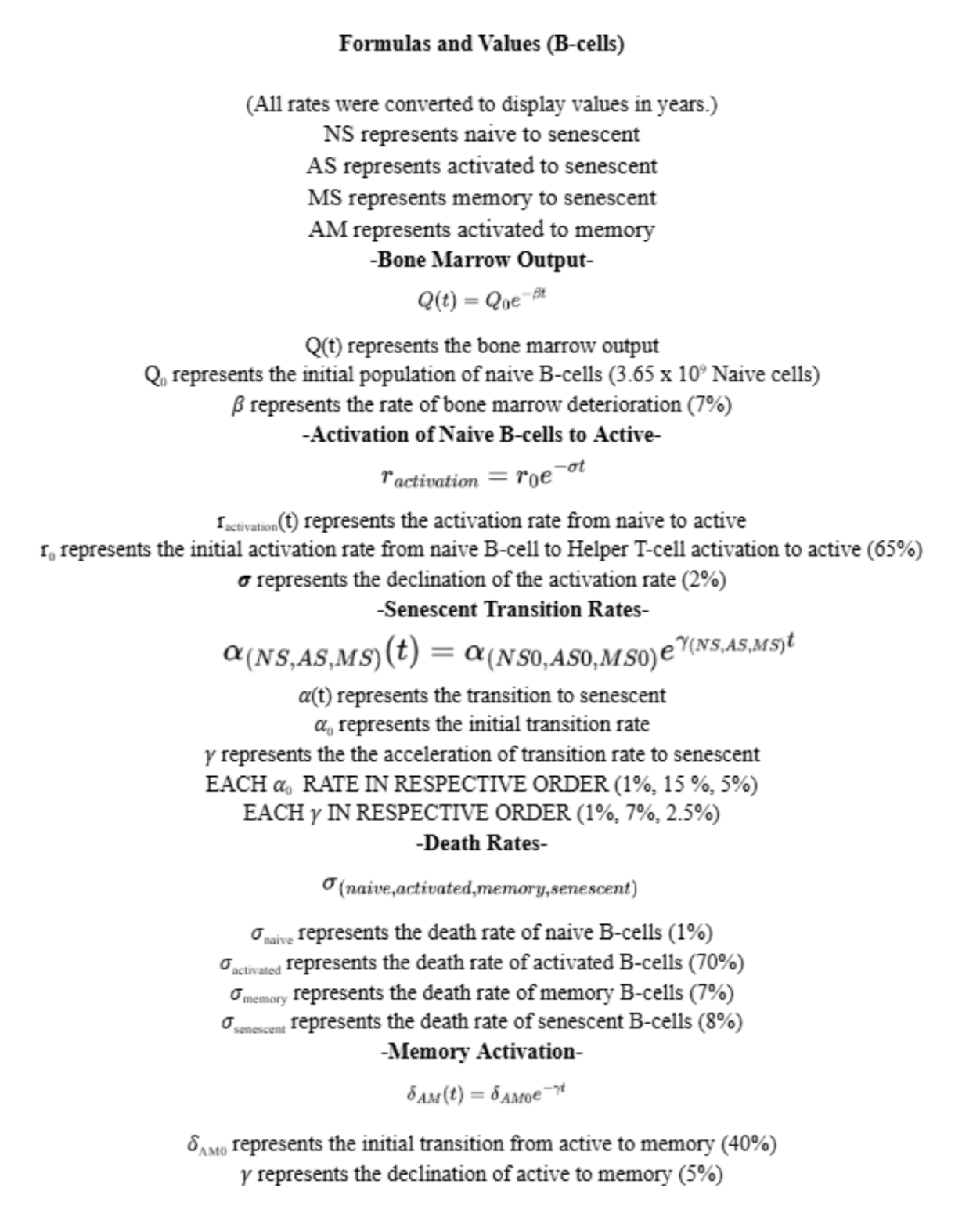

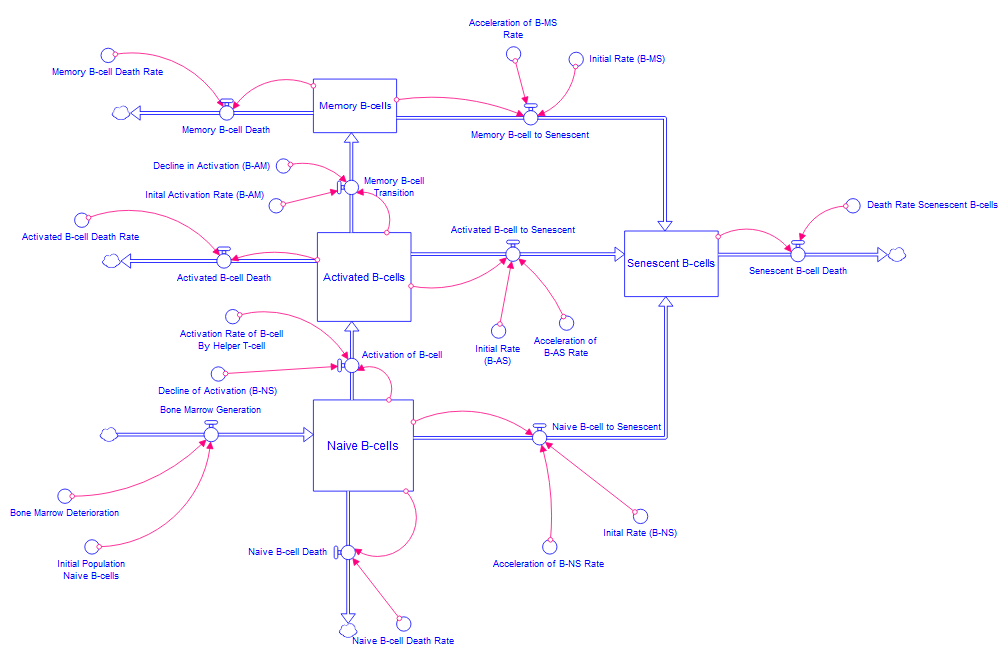

Next, we tasked ChatGPT to help craft a set of equations that would reflect the B-cell population dynamics. It crafted similar equations to the T-cells and sub-formulas (Fig. 2) also followed the same structure; however, the rates differed from the T-cells to reflect the unique dynamics the B-cell population undergoes.

Figure 2:Rates and sub-formulas of B-cell population

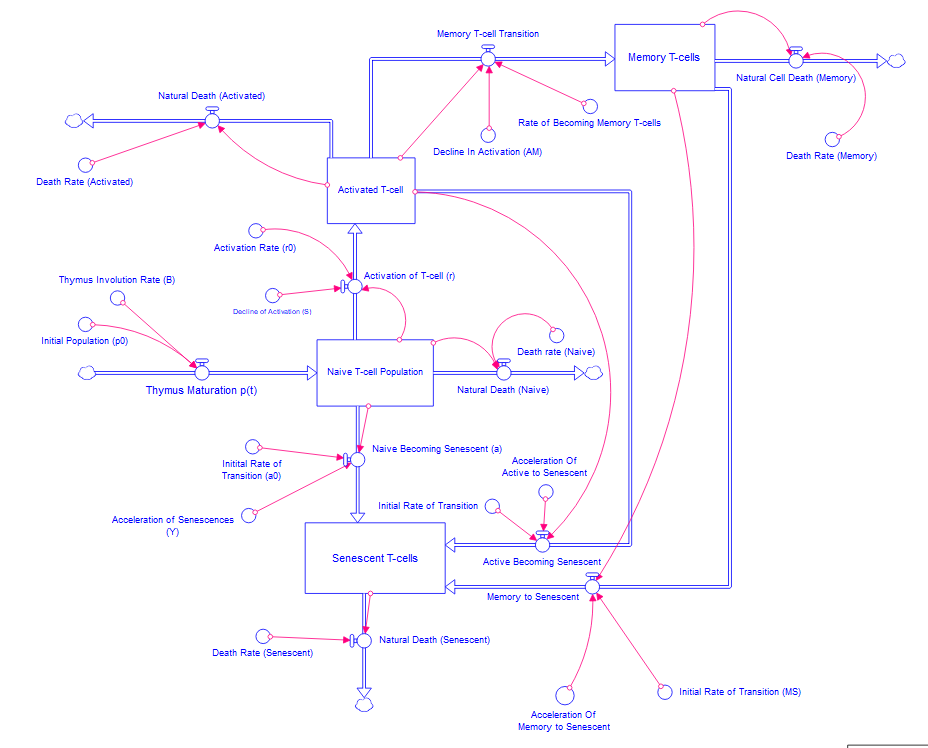

Equation (5) represents the dynamics of naive B cells, while Equation (6) represents the dynamics of activated B-cells. Additionally, Equation (7) represents the population dynamics of memory B-cells, and Equation (8) represents the dynamics of senescent B-cells. Following the development of differential equations, it is important to select an appropriate computational tool to visualize the dynamics to gain a deeper understanding of the relationships between the various rates. Stella Architect has been identified as a suitable platform for this purpose, owing to its strong capabilities in system dynamics modeling. The interface of Stella facilitates the creation of stock-and-flow diagrams, which effectively illustrate the transitions among different cell states and the underlying physiological processes. In this framework, stocks denote populations of naive, activated, memory, and senescent cells, while flows represent the transition of activation, senescence, and cell death. Additionally, converters and connectors are utilized to incorporate the various rates into the model. The simulation was conducted using the RK4 method (Runge-Kutta Method), which is recognized for its precision and higher-order capabilities in evaluating differential equations accurately. The models constructed can be seen in Figure 3 and Figure 4. In preparation for the generation of the graphs, the axes have been labeled appropriately, with the x-axis denoting the years following the age of 60 and the y-axis representing the population.

Figure 3:Constructed Stella model of T-cell population dynamics

Figure 4:Constructed Stella model of B-cell population dynamics

Results and Discussion¶

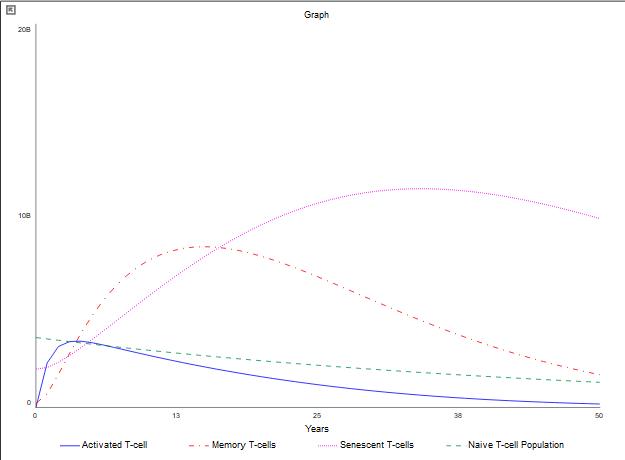

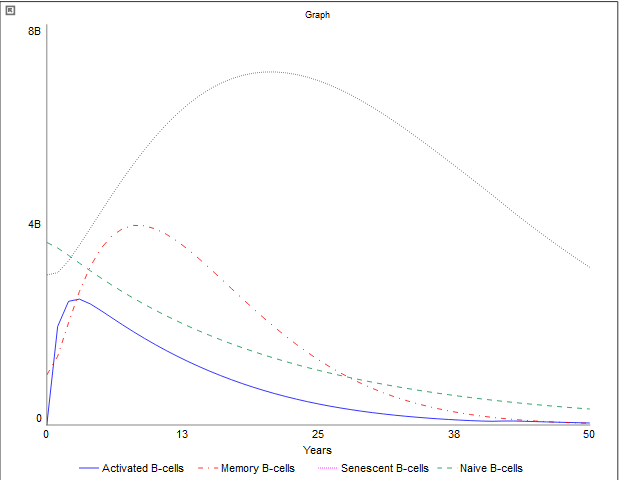

The models ran and two line graphs were produced for each population to display their respective dynamics with each line graph showing the four unique populations. The results accurately reflect the long-term effects of aging on T-cells and B-cells, activation, death, and turnover.

In the context of T-cells, as illustrated in Figure 5, the population of naive T-cells exhibits a gradual decline over time, ultimately approaching zero. After 50 years, the quantity of naive T-cells is significantly lower than at the outset, with only a few million remaining. This reduction can primarily be attributed to thymic involution. Naive T-cells show a lower propensity for apoptosis, and their turnover to senescent cells is relatively minimal in comparison to the overall T-cell population. The decline in naive T-cells has a major effect on all T-cell populations, particularly the active T-cells. As the population of naive T cells diminishes, the population of active T-cells also decreases. The rates selected within this model accurately reflect these dynamics. The elevated death rate, declining activation rate, and increased turnover rate to senescent cells in activated T-cells suggest a significant decline over time, illustrating that the immune response weakens as one ages. Furthermore, it is important to note that activated T-cells transition to the senescent state at a faster rate than other T-cell populations. The memory T-cell population, being the second most abundant in the model, reflects a low senescent turnover rate and death rate. This phenomenon explains why the decline in the populations of naive and activated T-cells does not significantly impede the number of memory T-cells. Nevertheless, a trend exists indicating a reduction in memory T-cell population over time, due in part to the decreased activation rate of active T-cells converting to memory T-cells, as well as the mortality and senescence of older T-cells. This trend further underscores the weakening of the immune system. Ultimately, senescent T-cells emerge as the dominant population as time progresses, as all other T-cell populations, particularly the active T-cells, contribute to this accumulation. Senescent T-cells do not undergo rapid apoptosis and thus accumulate within the body, subsequently diminishing immune responses. This relationship is evidenced by the substantial increase in senescent T-cells alongside the decline in the active T-cell population.

In the context of B-cells, having very similar trends as illustrated in Figure 6, the population of naive B-cells experiences a gradual decline over time, ultimately approaching zero. After 50 years, the quantity of naive B-cells is markedly reduced compared to the initial count, with only a few million remaining. This reduction is primarily attributable to diminished bone marrow output. Naive B-cells, like naive T-cells, exhibit a lower propensity for apoptosis and their turnover. The decline in naive B cells has a major impact on all B-cell populations, particularly active B-cells. As the population of naive B-cells diminishes, there is a corresponding decrease in the active B-cell population. The rates selected within this model accurately reflect these dynamics. The elevated death rate, declining activation rate, and increased turnover to exhausted cells in active B cells indicate a substantial decline over time, illustrating the weakening of the adaptive immune response as individuals age. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that active B-cells transition to an exhausted state at a faster rate than other B-cell populations. The memory B-cell population, the second most abundant in this model for a while, demonstrates a low turnover and death rate concerning exhaustion. This observation elucidates why the decline in naive and active B-cells does not significantly hinder the number of memory B-cells. Nevertheless, there exists a discernible trend indicating a gradual reduction in the memory B-cell population over time, attributable in part to the decreased activation rate of naive B cells converting into memory B-cells, as well as the mortality and exhaustion of older B-cells. However, towards the end of the graph, the naive B-cells gain the second most abundance as theactive B-cells population has significantly decreased and the active to memory rate has declined a large amount. Conclusively, senescent B-cells emerge as the predominant population as time progresses, since all other B-cell populations, particularly active B-cells, contribute to this accumulation. Senescent B-cells do not undergo rapid apoptosis, leading to their accumulation within the body and subsequently diminishing immune responses. This relationship is evidenced by a marked increase in exhausted B-cells alongside the decline in the active B-cell population. These graphical figures demonstrate the active differences between T-cells and B cells as B-cells exhaust faster due to their function.

The results accurately reflect existing scientific evidence/knowledge. Both graphical figures demonstrate a declining trend in the function and population of T-cells and B-cells. The population of naive T-cells is crucial for maintaining the balance of other immune cell populations, except for senescent cells. As indicated by the graphs, the decline in naive T-cells over time will inevitably lead to a decrease in memory and active cell populations. This illustrates the negative effects of thymic involution and bone marrow deterioration on these immune cell populations. The results also show that the rates of senescent cells accelerate over time, making the senescent cell population the most dominant among individuals aged 60 and older which aligns with the fact that senescent T-cells and B-cells will dominate the other populations and weaken immune responses. While the model offers valuable insights, its simplified assumptions may not fully capture the complexities associated with immune aging. Future iterations of the model could enhance predictive accuracy by incorporating more non-linear dynamics, environmental influences, and factors from earlier life stages. Despite these limitations, the findings highlight the potential to mitigate the impacts of immunosenescence and improve health outcomes for aging individuals. This model has effectively reflected information corroborated by other studies, which is valuable as it paves the way for future models.

The findings of this study present significant opportunities for future research focused on addressing immune aging and its associated consequences. One particularly promising area involves the development of interventions aimed at mitigating immune senescence. Strategies such as thymic rejuvenation, stem cell therapies, and pharmacological agents designed to enhance bone marrow output could be beneficial in maintaining populations of naive T-cells and B-cells. Additionally, targeting the pathways involved in T-cell senescence and B-cell exhaustion may provide therapeutic avenues to support immune function in the aging population. Furthermore, it is essential to explore the influence of environmental and lifestyle factors on immune dynamics. Research may investigate how dietary choices, physical exercise, and exposure to pathogens impact immune aging. Moreover, studies examining whether interventions such as caloric restriction or customized exercise programs can improve immune resilience over time will be valuable. Future research should also consider the intricate interactions between T-cells and B-cells. Analyzing how fluctuations in one population affect the other, particularly about cytokine signaling, could yield critical insights into the maintenance of balanced immune responses. Investigation on inflammation was missing from this model and could be a factor incorporated in future research as the majority of elderly suffer from chronic inflammation and this factor has effects on T-cells and B-cells. Finally, investigations into age-related diseases and the efficacy of vaccinations among older populations may have substantial applications. A deeper understanding of how immune senescence contributes to conditions such as cancer or chronic infections could guide the development of targeted treatments. Additionally, optimizing vaccine design may enhance protective measures for aged individuals. These factors could all be possible future studies that could generate more accurate models of the immune system and enhance our understanding of the interconnectedness of certain factors and cell population dynamics.

Figure 5:T-cell population graph 50 years later (after 60)

Figure 6:B-cell population graph 50 years later (after 60)

Conclusions¶

In conclusion, this research aimed to address the question of how to computationally model the factors of aging that influence the populations of T-cells and B-cells in humans aged 60 years and older. The study successfully developed differential equations, aided by contributions from ChatGPT, to facilitate the modeling of these cellular dynamics that accurately reflect factual information. In addition, Stella models were constructed which closely correspond to established scientific knowledge regarding the impact of the aging process on the immune system. The findings reveal that while the population dynamics of T-cells and B-cells exhibit nonlinear characteristics, a systematic approach can still produce accurate models aligning with factual ideas. However, the modeling process underscores the inherent complexity of population dynamics, due to the involvement of multiple factors that vary significantly among individuals. Consequently, the creation of a single universal model that accurately represents all individuals remains unfeasible. Nevertheless, this research presents opportunities for expansion by incorporating additional factors and real-life scenarios into the model. It could give us insights into understanding age-related immune decline, developing better therapies, or personalizing medicine and its effects on the immune system.

In conclusion, this research provides a comprehensive quantitative modeling and analysis of the aging immune system, establishing a foundational framework for subsequent studies aimed at enhancing health outcomes within aging populations. It emphasizes the significance of computational models in informing interventions designed to study, potentially mitigating the immune decline in older humans while expand knowledge and uncovering mysteries of immune science.

We sincerely thank Mr. Robert Gotwals for his invaluable guidance and support throughout this project, and course, and for allowing this independent research. Special thanks to the North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics for providing the software necessary for our research. We acknowledge the authors of the sources that contributed valuable background information. Additionally, the author is grateful to personal instructors for their feedback on this paper. Finally, heartfelt thanks go to friends and family for their unwavering support during the process of conducting the research.

Copyright © 2024 Zhu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, which enables reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the creator.

- Weyand, C. M., & Goronzy, J. J. (2016). Aging of the Immune System. Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targets. Annals of the American Thoracic Society, 13(Supplement_5), S422–S428. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201602-095AW

- Thymic involution. (2025). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Thymic_involution&oldid=1267397385

- Reitman, E. (n.d.). Yale Study Finds Aging of Bone Marrow Accelerates Atherosclerotic Plaque Formation. https://medicine.yale.edu/news-article/yale-study-finds-aging-of-bone-marrow-accelerates-atherosclerotic-plaque-formation/

- B cell. (2025). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=B_cell&oldid=1279553599

- ChatGPT. (n.d.). https://chatgpt.com