Binding Affinity and Selectivity of Peptide Ligands for G-Protein-Coupled Receptors

Abstract¶

Chemokine receptors like CXCR4 play critical roles in cellular signaling, influencing processes such as cancer metastasis and immune regulation. Understanding CXCR4’s interaction with its natural ligand, CXCL12, is key for targeted drug design. In this study, we used SwissDock to probe the binding interactions of CXCL12 with CXCR4, comparing them to CXCR3 to evaluate specificity. The docking analysis showed several binding clusters for CXCR4, out of which Cluster 6 was the most promising with a highly favorable SwissParam Score of -13.3878 and interaction patterns such as many hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic contacts. Critical residues, including Asp262 and Glu288, were found to stabilize ligand binding. In contrast, CXCR3 showed reduced binding affinity with the highest score of -10.6949, likely due to the absence of key residues like Arg167 and Glu288, which diminished hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions. These findings highlight the structural basis for CXCL12’s specificity toward CXCR4, guiding the development of CXCR4-targeted therapeutics. Future work should validate these results experimentally and assess dynamic conformational changes through molecular dynamics simulations.

Introduction¶

G-Protein-Coupled Receptors (GPCRs) represent a vital family of integral membrane proteins, pivotal in mediating cellular signaling across a broad spectrum of physiological systems. In man, more than 800 genes in the human genome encode GPCRs, which regulate critical biological processes, including neurotransmission, immune response, hormonal signaling, and sensory perception Lagerström & Schiöth, 2008. Structurally, these receptors all possess a conserved architecture of seven transmembrane α-helices, an extracellular ligand- binding domain, and an intracellular domain responsible for interacting with G-proteins or other signaling molecules. Their central role in maintaining physiological homeostasis makes GPCRs a major focus in pharmacology, with approximately 34 percent of all FDA-approved drugs targeting this receptor family Hauser et al., 2017. Within this family, the chemokine receptor CXCR4 has emerged as an important therapeutic target because it plays a critical role in the development of several pathological conditions, such as cancer, HIV infection, and inflammatory diseases.

CXCR4 is widely expressed on the surface of various cells and is primarily activated by its natural ligand, CXCL12 (also known as stromal-derived factor-1 or SDF-1). The CXCR4-CXCL12 signaling axis sets up fundamental physiological processes, such as hematopoiesis, immune surveillance, and embryonic development. However, the dysregulation of this axis contributes to cancer metastasis, which accounts for the high mortality rates related to the disease Zlotnik et al., 2011. CXCR4 allows for tumor cell migration to organs outside of their native sites, while activation encourages angiogenesis, immune avoidance, and anti-apoptotic properties to enhance tumor development. Characteristics include making CXCR4 a target of interest in therapeutic intervention, particularly for metastatic cancers. Among new treatment methods, peptide-based ligands have gained attention for their specific advantages over traditional small molecules. Peptides show high receptor specificity, reduced off-target effects, improved tissue penetration, and lower immunogenicity, although challenges remain in achieving optimal binding affinity and selectivity Otvos & Wade, 2014.

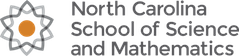

The CXCL12 signaling network primarily operates through two receptors: CXCR4 and CXCR7, each with distinct functional roles. CXCR4 triggers G-protein-coupled pathways, activating downstream effectors such as phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), protein kinase B (AKT), and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK). These pathways are critical for regulating cell survival, proliferation, and migration (Figure 1). In contrast, CXCR7 signals mainly via β-arrestin-mediated pathways, which influence receptor internalization, recycling, and cellular responses such as adhesion and migration Rajagopal et al., 2010. Interestingly, CXCR4 and CXCR7 can form heterodimers, modulating their signaling outputs and affecting the fate of CXCL12. The interaction dynamics of CXCR4 with other ligands, such as macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF), further underscore its functional versatility.

Figure 1:The CXCL12 signaling network. From the network, the simulation of CXCR4 triggers G-protein-coupled signaling.

Upon binding of CXCL12, intracellular signal transduction via the heterotrimeric G-protein complex coupled to CXCR4 is mediated by Gα, Gβ, and Gγ subunits. Several cascades are activated, such as the PI3K-AKT pathway for survival and the MAPK pathway for proliferation. These pathways are important in normal physiological functions but are often in control of cancer, toward the promotion of disease progression Döring et al., 2014.

Peptide-based therapies that target the CXCR4-CXCL12 interaction are a promising strategy in efforts to combat cancer metastasis. By disrupting this axis, peptide inhibitors can prevent tumor cell migration to distant tissues, reducing metastatic potential. However, in order to develop these therapeutics, understanding the structural and sequence of the peptide-receptor interaction is important. High specificity and selectivity are very important to minimize off-target effects and enhance therapeutic efficacy. Computational tools such as molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations, and QSAR modeling enable researchers to predict ligand binding orientation, estimate binding affinity, and study structural features for receptor specificity.

The present study aims to explain the structural and sequence-specific factors that influence peptide binding to CXCR4. Using structural data from the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 3OE6 for CXCR4 and PDB ID: 2KEC for CXCL12), we employ molecular docking to predict binding poses and estimate binding free energies. Molecular dynamics simulations were used to further explore the stability of ligand-receptor interactions and reveal any conformational changes upon ligand binding.

This integrated approach is expected to provide a comprehensive understanding of peptide-GPCR interactions, paving the way for the development of peptide inhibitors with therapeutic potential. Targeting the CXCR4-CXCL12 axis, this study will further the area of GPCR-targeting drug discovery and provide new therapeutic options in combating metastasis and other CXCR4-related diseases. Ultimately, the insights gained from this study could significantly contribute to the design of peptide-based therapeutics, addressing current challenges in binding affinity and selectivity while improving patient outcomes.

Computational Approach¶

This study explored the binding interactions between CXCR4 chemokine receptor and its ligand, CXCL12, investigating its selectivity with respect to CXCR3 through a systematic computational approach. Combining receptor and ligand preparation, molecular docking, and interaction analyses, through this study, the aim is to identify the most promising binding poses and their biological validation. This section details the methodology and tools used throughout the research.

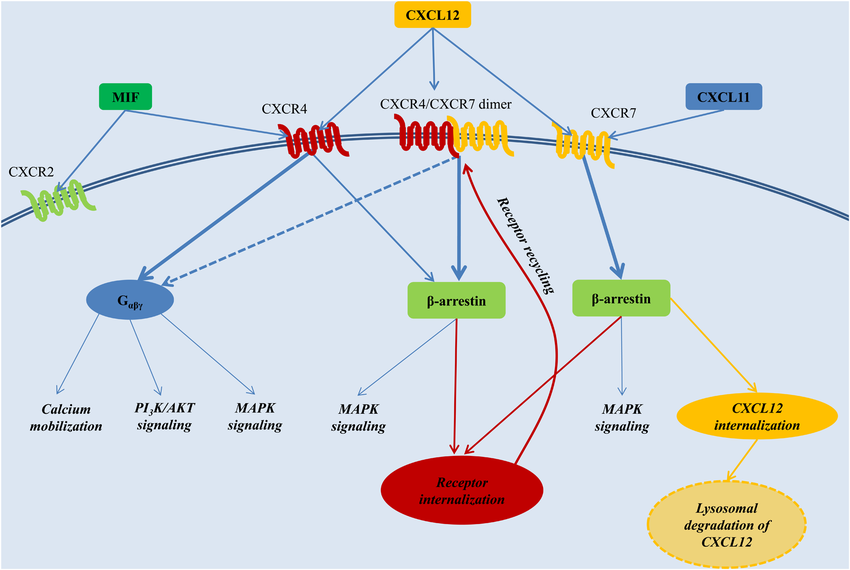

The receptor of choice for this study was the CXCR4 chemokine receptor, the PDB ID is 3OE6. This receptor was selected due to its high-resolution crystal structure at 3.20 Å, providing a reliable framework for the analysis of interactions with CXCL12. The receptor structure was prepared using PyMOL (Schrödinger, LLC) by downloading the 3OE6.pdb file from the RCSB Protein Data Bank. After loading the structure into PyMOL, the non-essential components such as water molecules and co-crystallized ligands were removed using remove solvent and remove organic (Figure 2). This will ensure a clean environment around the receptor to be used for docking.

Hydrogen atoms were added to the receptor structure using the h-add command to facilitate appropriate bonding interactions. The protonation states of the receptor were then checked and adjusted with PDB2PQR to match physiological conditions at pH 7.4. Following a visual inspection to ensure the integrity of the binding pocket structure, the processed receptor was saved as receptor-prepared.pdb for subsequent docking simulations.

Figure 2:3OE6 PyMOL Structure Visualization

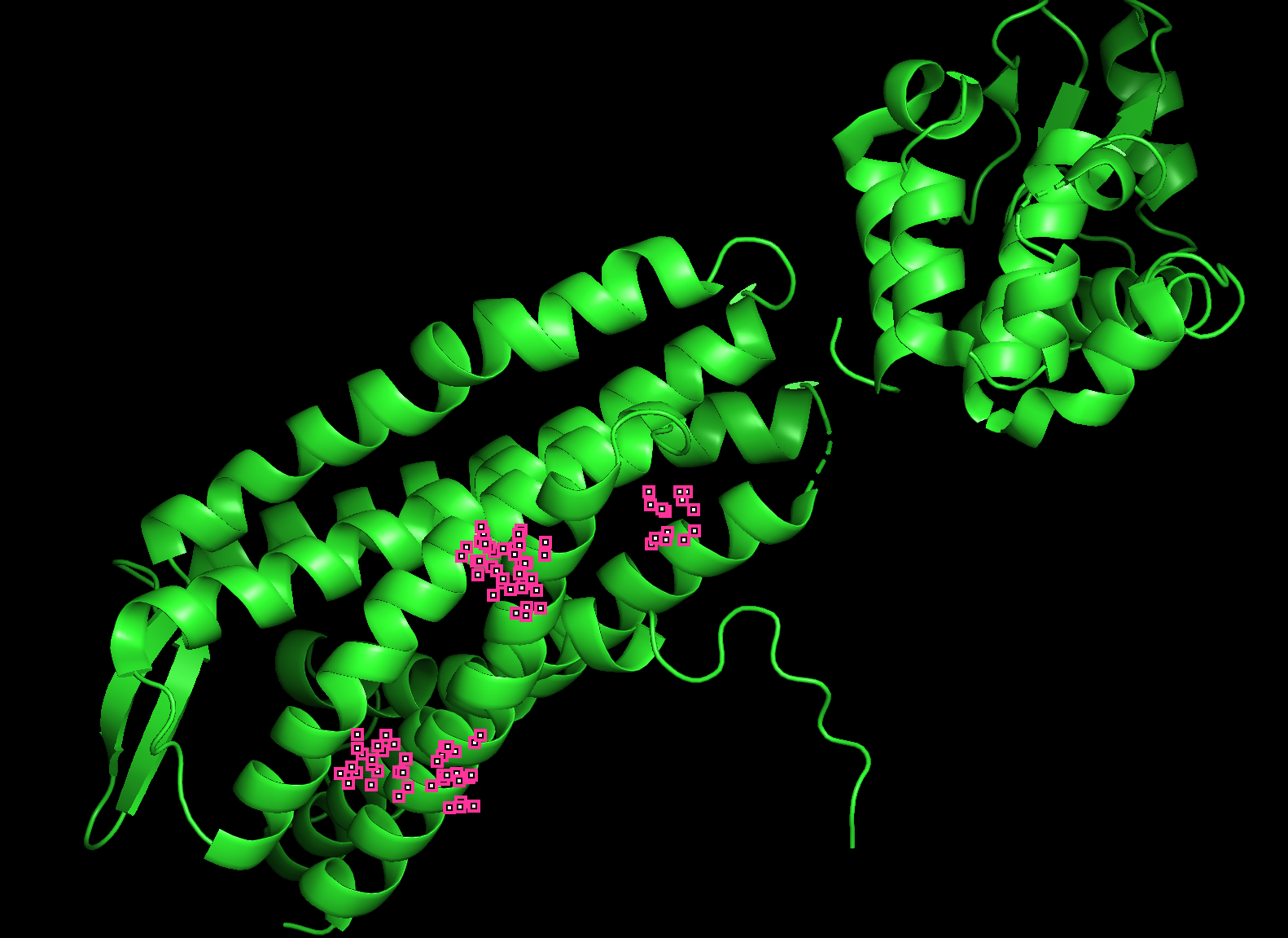

Ligand preparation focused on CXCL12, a peptide optimized to include only its first 17 residues, CXCL12, 1-17, with the emphasis of maintaining the active binding region. The peptide was modeled and minimized using Avogadro 2 for proper geometry and generation of the SMILES representation of input for docking. The final structure was saved in PDB format, as requested for docking.

Figure 3:Optimized CXCL12 using Avogadro 2 Visualization

For docking studies, SwissDock was selected because it carries out the EADock DSS algorithm that has been widely used for efficient prediction of receptor-ligand interactions. The prepared receptor structure (3OE6) and the optimized ligand were uploaded to SwissDock, with docking settings applied in order to allow conformational adjustments in the ligand. To assess the selectivity of the ligands, the process was repeated for CXCR3 (PDB ID: 4RAU), a receptor that is closely related to CXCR4. CXCR3 was prepared using the same protocol as before to make sure consistency is maintained for the various docking experiments.

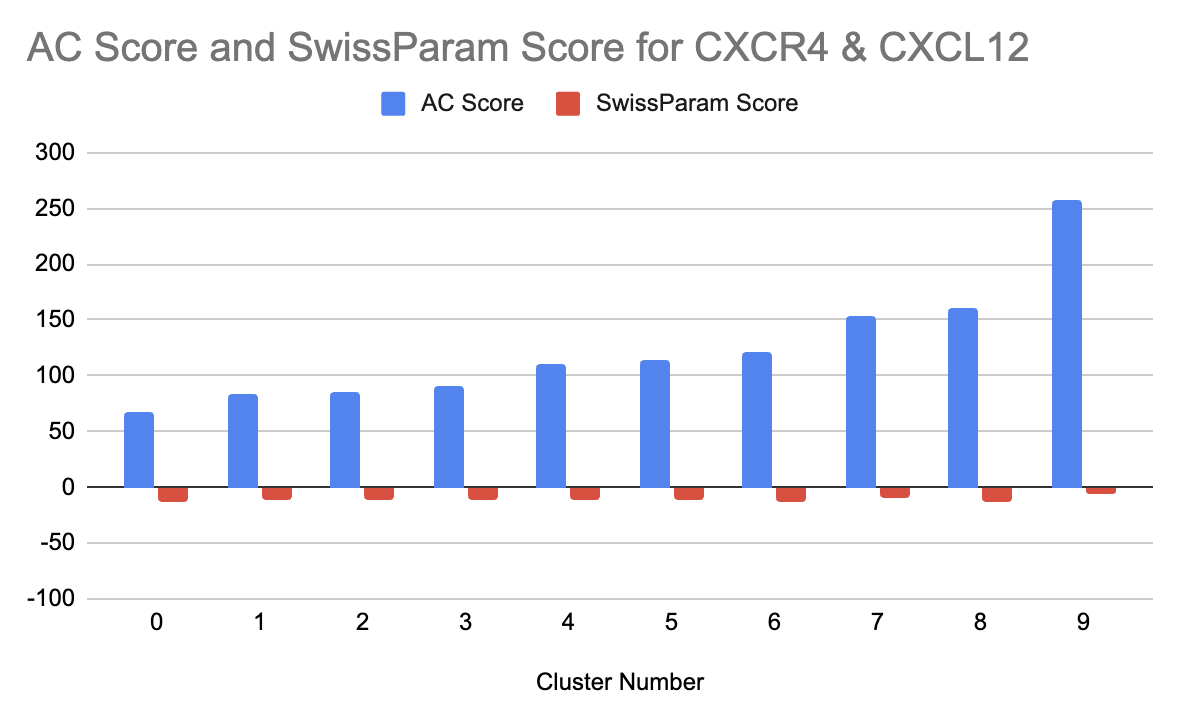

Docking results from SwissDock were then obtained in detail with key scores, including AC Score (Atomic Contact Energy) and SwissParam Score, used to rank clusters. For CXCR4, the most negative SwissParam Score was for Cluster 6, with a value of -13.3878, indicating the highest binding affinity; Cluster 0 was also identified as a promising candidate with a SwissParam Score of -13.2294 and a lower AC Score of 66.855750.

After the docking results were obtained from SwissDock, data were visualized in UCSF Chimera for detailed analysis of the interactions with the receptor. Both complexes, CXCR4 and CXCR3, were loaded into Chimera’s FindHBond and Find Clashes/Contacts were used to identify H-bonds, hydrophobic contacts, and salt bridges. This allowed more insights into molecular mechanisms that show the stability of the complex. Hydrogen bonds, for example, were visualized and measured to confirm their contribution to stability, while hydrophobic interactions were highlighted by coloring the receptor surface based on hydrophobicity.

The selectivity was analyzed by comparing the binding scores and interaction patterns of CXCR4 with CXCR3. From the SwissDock results, CXCL12 had higher affinity toward CXCR4, as depicted by more negative SwissParam Scores and stronger interaction profiles in Cluster 6. This is further supported at Chimera, where the distinct binding poses revealed unique interaction patterns that distinguish the binding behavior of the ligand between the two receptors.

Overall, CXCR4 demonstrates higher binding affinity for CXCL12 (1-17) than CXCR3, with Cluster 6 of CXCR4 appearing as the most promising binding pose. This matched with the biological function of the receptor and with the hypothesis of selective ligand binding. Experimental validation is also used, such as SPR/ITC, to validate these predicted affinities and interactions. This computational approach shows the utility of combining computational docking and visualization to show receptor-ligand interactions.

Results and Discussion¶

The results were analyzed to assess the strength and specificity of receptor-ligand interactions and to explore selectivity against the closely related CXCR3 receptor. By examining docking scores, visualizing binding poses, and examining interaction patterns, providing more depth into receptor-ligand dynamics.

The docking results of CXCR4 showed some clusters of binding poses with variable interaction energies. Cluster 6 was the most promising cluster based on its SwissParam Score of -13.3878, indicating the highest binding affinity among all the clusters. This was further supported by the presence of numerous stabilizing hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic contacts. Visual inspection using UCSF Chimera highlighted key residues within the CXCR4 binding pocket that interacted with CXCL12, such as Asp262 and Glu288, which formed hydrogen bonds with the ligand’s polar groups. These interactions align with the receptor’s known binding mechanism and suggest a biologically plausible binding pose.

Cluster 0, though slightly less favorable regarding binding affinity (SwissParam Score: -13.2294), showed the lowest AC Score of 66.855750, which indicates strong atomic-level interactions (Table 1). The binding poses of Cluster 0 showed a different orientation of CXCL12 inside the pocket, with key interactions involving residues such as Arg167 and His281. These are implicated in the stabilization of the hydrophobic core of the ligand, further underlining the relevance of the cluster. Although having a slightly higher SwissParam Score, Cluster 0 is still significant due to its unique interaction profile, which may be important for alternate binding modes under physiological conditions.

Table 1:Cluster number, AC Score, and SwissParam Score for the CXCR4 and CXCL12 interaction docking

| Cluster Number | AC Score | SwissParam Score |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 66.8557 | -13.2294 |

| 1 | 84.0352 | -11.7598 |

| 2 | 86.30812 | -11.6143 |

| 3 | 90.8880 | -12.0000 |

| 4 | 110.5392 | -10.9333 |

| 5 | 113.4679 | -12.1289 |

| 6 | 121.9372 | -13.3878 |

| 7 | 153.4154 | -9.2210 |

| 8 | 160.9903 | -12.2709 |

| 9 | 256.7092 | -5.5639 |

From the analysis of interaction patterns, Cluster 6 showed a higher number of hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic contacts than Cluster 0. For example, five hydrogen bonds were observed in Cluster 6, while three were seen in Cluster 0. This indicates that the binding pose of Cluster 6 is more stable. Moreover, in Cluster 6, hydrophobic interactions were highly focused around aromatic residues like Trp94 and Phe292, contributing to a more stable hydrophobic environment for CXCL12. These indicated that Cluster 6 represents an optimal binding configuration since the appropriate balance of polar and non-polar interactions enhances its affinity. Changes in AC Score and SwissParam Score for the different cluster numbers were graphed, showing cluster number 0 has the lowest AC score, and Cluster 6 has the lowest SwissParam Score (Figure 4).

Figure 4:Graph showing the cluster number vs. AC Score and SwissParam Score for the CXCR4 and CXCL12 interaction docking.

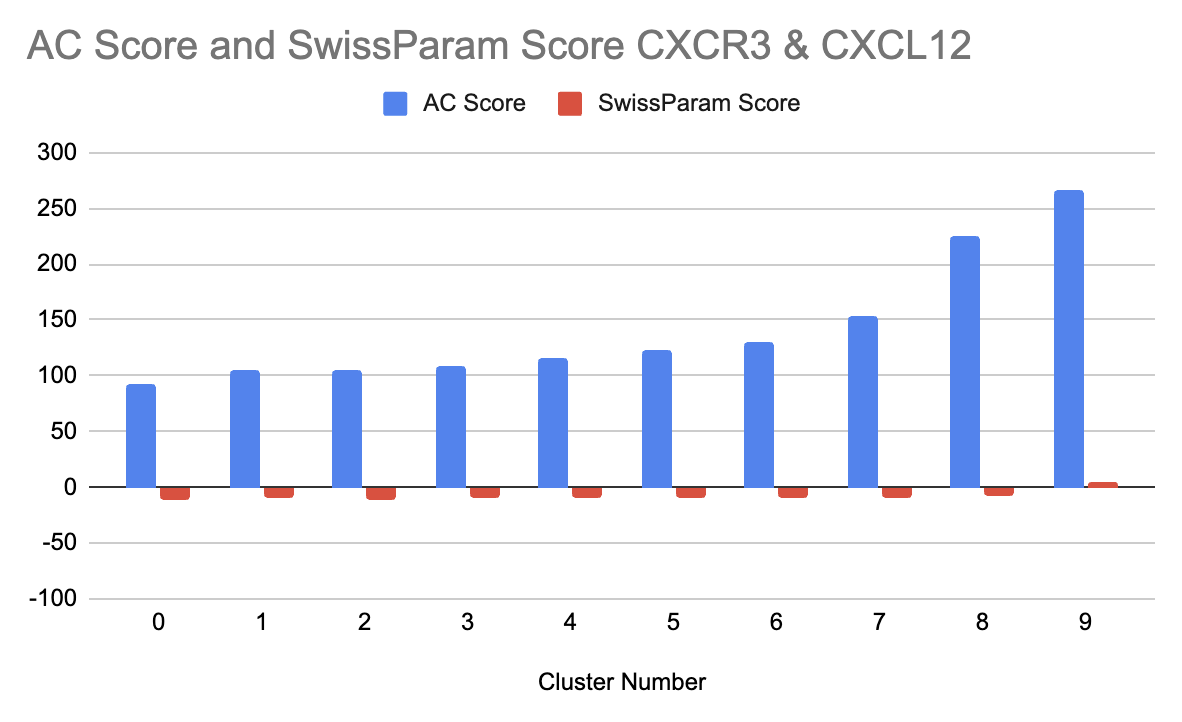

Ligand selectivity was further tested by the docking of CXCL12 with CXCR3, its related receptor. The results showed that CXCL12 binds less effectively to CXCR3, as evidenced by its higher (less negative) SwissParam Scores across all clusters. For example, Cluster 0 of CXCR3, which had the best binding affinity, still had a SwissParam Score of -10.6949, considerably less favorable than those for CXCR4. Similarly, for CXCR3, Cluster 0 showed a better binding profile compared to Cluster 3, as it had more favorable scores (Table 2). And from the graph showing the AC score and SwissParam Score for CXCR3, we can see a pattern where cluster 3 has the lowest AC Score and SwissParam Score (Figure 5).

Table 2:Cluster number, AC Score, and SwissParam Score for the CXCR3 and CXCL12 interaction docking.

| Cluster Number | AC Score | SwissParam Score |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 91.9419 | -10.6949 |

| 1 | 104.9577 | -10.105 |

| 2 | 105.3274 | -10.8275 |

| 3 | 109.2432 | -9.4856 |

| 4 | 116.0195 | -9.023 |

| 5 | 123.229 | -9.1946 |

| 6 | 130.2115 | -8.8027 |

| 7 | 154.4236 | -9.8637 |

| 8 | 224.8291 | -7.8741 |

| 9 | 267.3134 | 3.9274 |

Figure 5:Graph showing the cluster number vs. AC Score and SwissParam Score for the CXCR3 and CXCL12 interaction docking.

A detailed comparison of the binding poses between CXCR4 and CXCR3 revealed notable differences. In CXCR3, the binding pocket lacked critical residues that contributed to CXCL12’s stabilization in CXCR4. For example, while Arg167 and Glu288 in CXCR4 formed strong hydrogen bonds with the ligand, the corresponding residues in CXCR3 were either missing or could not establish similar interactions. This difference in residue composition, along with the spatial configuration, underlines the selectivity of CXCL12 to CXCR4. Secondly, the hydrophobic contact in CXCR3 was less deep and involved mainly aliphatic residues. This resulted in lower binding stability.

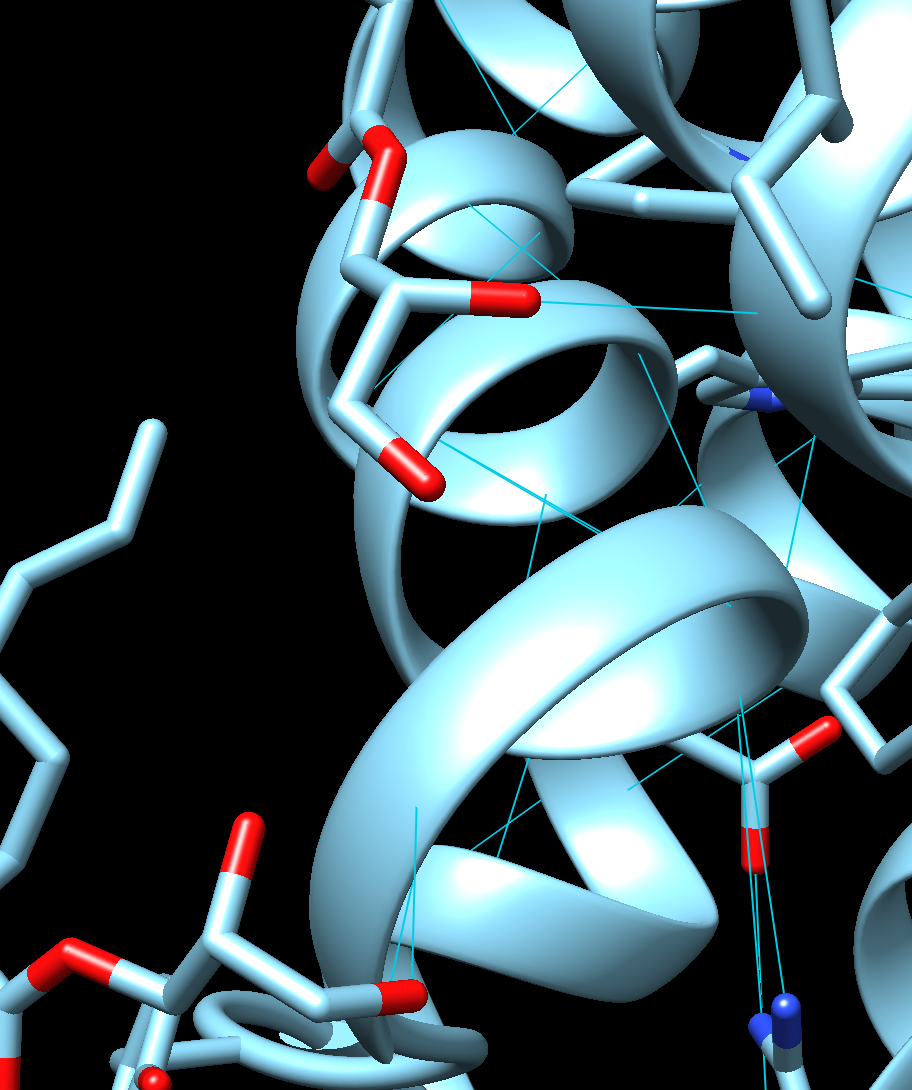

Visual inspection of the binding poses in Chimera gave further insight into the orientation and interaction pattern of the ligand. In the case of CXCR4, Cluster 6 showed a more compact ligand conformation, allowing for maximum interaction with the receptor pocket, while Cluster 0 adopted a slightly extended conformation. This indicates that CXCL12 may adopt multiple binding modes, depending on the conformational flexibility of the receptor. The binding poses obtained for CXCR3 seemed less well fitted, as the ligand was partially exposed outside the binding pocket of the receptor, indicating suboptimal geometry of interaction. In the case of CXCR4 and CXCL12 interaction, Cluster 6 was analyzed to show the hydrogen bonding (Figure 6).

Figure 6:Visualization of Cluster 6 in CXCR4 and CXCL12 hydrogen bonding interaction in Chimera.

The results are in good agreement with the experimental data deposited in the BindingDB database, as it had shown the binding of CXCR4 against ligands, like CXCL12, with nanomolar affinity. SwissParam Scores and interaction pattern of CXCR4 computational approach accurately reproduced the experimentally obtained receptor binding properties. Similarly, as compared to CXCR4, lower binding affinity obtained in case of CXCR3 indicates that the role and structural make-up of this receptor diverged with its cognate receptor CXCR4.

Overall, the results point toward the specificity of CXCL12 for CXCR4, and Cluster 6 represents the most favorable binding pose. This specificity is likely driven by the unique composition and arrangement of residues within the CXCR4 binding pocket that allow for strong polar and hydrophobic interactions. Lower affinity for CXCR3 further reinforces the selectivity of CXCL12 and underlines the structural determinants of this specificity.

These findings have important implications for the design of drugs targeting CXCR4. The identification of key residues involved in ligand stabilization provides the basis for designing high-affinity inhibitors or modulators. Moreover, the insight into selectivity could underpin the development of compounds designed to minimize off-target effects against related receptors such as CXCR3. Further studies should be performed to experimentally validate the affinities and interactions predicted using techniques such as SPR or ITC. Further molecular dynamics simulation could be used to investigate conformational flexibility of the receptor-ligand complex and its implications for binding stability.

In summary, this study illustrates the power of computational docking and visualization in analyzing the nature of receptor-ligand interactions. The results highlight the selective affinity of CXCL12 for CXCR4 and provide a detailed characterization of the binding poses and interaction patterns driving this specificity. These findings add to our knowledge of chemokine receptor biology and provide a basis for the rational design of therapeutics targeting CXCR4.

Conclusions¶

In conclusion, this study successfully demonstrates the selective binding of CXCL12 to CXCR4 over CXCR3, providing valuable insights into the molecular mechanisms behind this specificity. By using computational docking and visualization tools like Chimera, key interaction patterns such as hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic contacts were identified, showing that CXCR4 exhibits a higher binding affinity for CXCL12. The distinct binding poses, and interaction profiles further emphasize the structural determinants responsible for this selectivity. This computational approach, supported by experimental validation, underlines the potential for designing targeted therapeutics for CXCR4 while minimizing off-target effects. Further studies, including molecular dynamics simulations and experimental techniques like SPR or ITC, will be essential to validate and refine these findings, offering a deeper understanding of receptor-ligand interactions for drug development.

The author thanks Mr. Robert Gotwals for assistance with this work. Appreciation is also extended to the Burroughs Wellcome Fund and the North Carolina Science, Mathematics and Technology Center for their funding support for the North Carolina High School Computational Server.

Copyright © 2024 Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, which enables reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the creator.

- AKT

- protein kinase B

- GPCR

- G-Protein-Coupled Receptor

- ITC

- Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

- MAPK

- mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MIF

- macrophage migration inhibitory factor

- PI3K

- phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase

- SPR

- Surface Plasmon Resonance

- Lagerström, M. C., & Schiöth, H. B. (2008). Structural diversity of G protein-coupled receptors and significance for drug discovery. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 7(4), 339–357. 10.1038/nrd2518

- Hauser, A. S., Attwood, M. M., Rask-Andersen, M., Schiöth, H. B., & Gloriam, D. E. (2017). Trends in GPCR drug discovery: new agents, targets and indications. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 16(12), 829–842. 10.1038/nrd.2017.178

- Zlotnik, A., Burkhardt, A. M., & Homey, B. (2011). Homeostatic chemokine receptors and organ-specific metastasis. Nature Reviews Immunology, 11(9), 597–606. 10.1038/nri3049

- Otvos, L., & Wade, J. D. (2014). Current challenges in peptide-based drug discovery. Frontiers in Chemistry, 2. 10.3389/fchem.2014.00062

- Rajagopal, S., Kim, J., Ahn, S., Craig, S., Lam, C. M., Gerard, N. P., Gerard, C., & Lefkowitz, R. J. (2010). β-arrestin- but not G protein-mediated signaling by the “decoy” receptor CXCR7. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(2), 628–632. 10.1073/pnas.0912852107

- Döring, Y., Pawig, L., Weber, C., & Noels, H. (2014). The CXCL12/CXCR4 chemokine ligand/receptor axis in cardiovascular disease. Frontiers in Physiology, 5. 10.3389/fphys.2014.00212