Exploring the Use of Immunotherapy Techniques in Lymphocytic Leukemia

Abstract¶

Lymphocytic leukemia is a cancer that affects the white blood cells. It occurs when the cancerous, abnormal cells outcompete and reproduce more efficiently than the healthy cells in the body. Although there are therapies like chemotherapy and radiation, these therapies often lead to relapse or are simply not effective. Emerging Immunotherapy techniques like immune checkpoint inhibitors and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR T-cell) therapy offer a new gaze into what can be done to use the body’s own immune system to apoptotic cancer cells. This research review paper monitors advancements made in immunotherapy, highlighting clinical trials and research done in Seoul, Munich, and New England that investigate drugs like Blinatumomab and CART19 therapies. Despite great progress, there still need to be more consistent results in trials, costs need to be lowered, and the efficiency of immunotherapy needs to be muchswifter. For future research, trials on other diseases using the same techniques need to be underway, and the applications of this miracle drug need to be fully explored and pioneered.

Introduction and Background of Lymphocytic Leukemia¶

Lymphocytic leukemia is a type of cancer that affects white blood cells, and these white blood cells cause blockages and can crowd out healthy blood cells, choking the bloodstream. Although the exact cause of leukemia is unknown, scientists believe that it may result from factors like genetics, lifestyle, and environmental exposures Pérez-Carretero et al., 2021. There are two different types of lymphocytic leukemia: acute lymphocytic leukemia and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Acute lymphocytic leukemia affects mostly children and younger adults, while chronic lymphocytic leukemia affects primarily older adults, though exceptions exist Sharma & Rai, 2019.

Like most cancers, lymphocytic Leukemia manifests more in the developed parts of the world, mainly in North America and Europe Carballido et al., 2012. There are many underlying mutations to lymphocytic leukemia, such as the Philadelphia chromosome, a translocation between chromosomes 9 and 22; the BCR-ABL1 fusion gene, which causes cancerous cells to exhibit abnormal tyrosine kinase activity; TP53 mutations, which confer resistance to therapy; and NOTCH1 mutations, which enable cell proliferation and differentiation Wang et al., 2021.

Acute lymphocytic leukemia requires expedited treatment, often leading to a lower life expectancy, while individuals with chronic lymphocytic leukemia may live for decades with sporadic and controlled treatment Eichhorst et al., 2016. Treatments for lymphocytic leukemia include chemotherapy, radiation, immunotherapy, and stem cell transplantation Porter et al., 2011. The likelihood of developing chronic lymphocytic leukemia is about 0.57%, or 1 in every 175 people in the United States, with men having a slightly higher risk Pérez-Carretero et al., 2021. For acute lymphocytic leukemia, the incidence is less than 1% of all cancer cases in the United States Vincent et al., 2011. Although acute lymphocytic leukemia primarily affects children, most deaths occur among adults, with 4 out of 5 deaths involving adult patients Sharma & Rai, 2019. The purpose of this paper is to highlight what research is being done to cure these ailments and ultimately make these statistics much more powerful with a deeper emphasis on the clinical trials and their criteria.

Immunology Methods to Prevent and Hinder Lymphocytic Leukemia¶

Figure 1:How Blinatumomab affects T-cells and apoptotic cancer cells

Scientists use immune checkpoint inhibitors and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy to treat lymphocytic leukemia Major et al., 2023. Immune checkpoint inhibitors target pathways like PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 to enhance and utilize T-cell responses against leukemia cells Carballido et al., 2012. CAR T-cell therapy involves genetically modifying the patient’s T cells to recognize and destroy cancer cells Porter et al., 2011.

A common method for leukemia cells to evade T-cell recognition is over-expressing PD-L1, which hinders T-cell function. When PD-L1 on a somatic cell binds to PD-1 on a T cell, it deactivates the T cell and leads to apoptosis Major et al., 2023. Immunotherapy techniques aim to block this interaction, enabling T cells to function and destroy leukemia cells Vincent et al., 2011.

In CAR T-cell therapy, scientists extract blood from patients, isolate the T cells, genetically modify them to target specific proteins on leukemia cells, and then reinfuse them into the patient Porter et al., 2011. Although this therapy shows remarkable success, it is costly and highly individualized Sharma & Rai, 2019.

Success rates for CAR T-cell therapy range between 30% and 40% depending on the modifications made Major et al., 2023. However, limitations include the high costs, unintended destruction of healthy blood cells, relapse risks, and side effects such as cytokine release syndrome (symptoms like coughing, low blood pressure, and organ dysfunction) and neurotoxicity (confusion, delirium, and nausea) Major et al., 2023. CAR T-cell therapy is ineffective against solid tumors Eichhorst et al., 2016.

The FDA has approved CAR T-cell therapy for treating B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia using drugs such as blinatumomab, nelarabine, and inotuzumab ozogamicin Sharma & Rai, 2019. Similarly, immune checkpoint inhibitors include drugs such as nivolumab, pembrolizumab, and cemiplimab Porter et al., 2011.

Research and Studies on Immunology Treatments for Leukemia¶

Seoul Trial

There was a study in 2019 in Seoul, South Korea, for lymphocytic leukemia, particularly referencing the recurrence around the marrow. The drug Idarubicin was used for the reinduction stage with the drug, Blincyto used for the study. This study is in stage 2, meaning that there are human trials and with people more at risk for any more cancer progression. A criteria for the patients for age was they must be at least more than one years old and at most 22 years old. The patients could not have received Blinatumomab before this study either. The study focused on many exclusion factors: patients should have adequate renal function, could not have the Philadelphia chromosome, could not have any mixed phenotypes for leukemia, and could not have had HIV either. Patients would be tested with Blinatumomab, and then the efficacy rate, disease-free survival rate, and death rate related to treatment would be tested. The patients would be tested for an average of 9 years.

Munich Trial

A recent Phase II clinical trial by Amgen Research (Munich) GmbH investigated the use of Blinatumomab (MT103) in targeting minimal residual disease of B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). The scientists used Blinatumomab to treat patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Blinatumomab doesn’t directly repair the Philadelphia Chromosome, but it can help eliminate leukemia cells that carry this abnormality. The inclusion criteria they used were that the patients must have B-precursor ALL and complete hematological remission with molecular failure, and must also be able to sign their informed consent to do so. Some of the exclusion criteria are that they do not have a history or have a current autoimmune disease, cannot have any anti-murine antibodies, cannot be pregnant or nursing either, and cannot have any current extramedullary involvement.

New England Trial

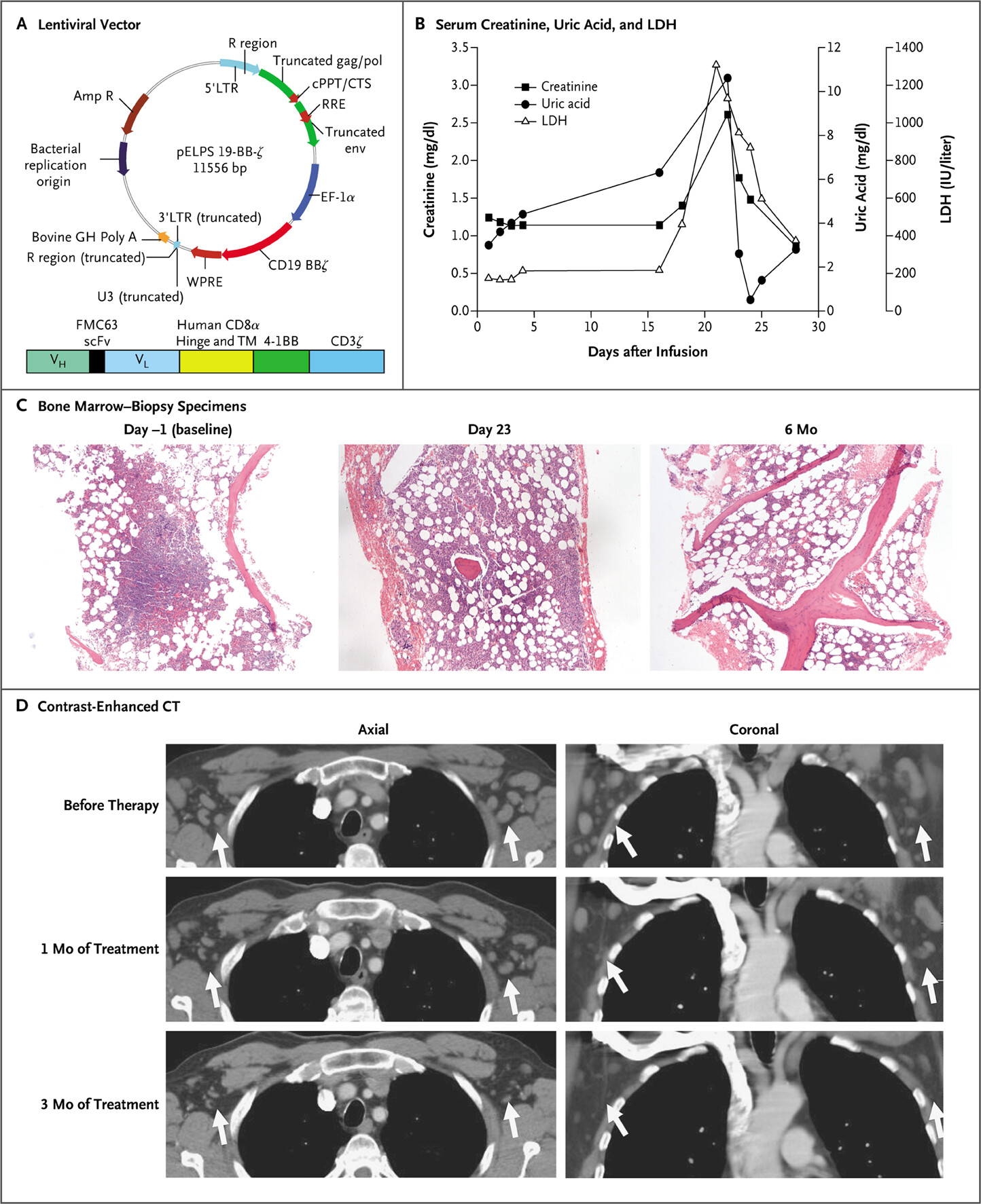

Another study in New England did a Phase 1 clinical trial that started with a patient diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) in 1996. The patient had treatment started in 2002, which was Rituximab plus fludarabine treatment (Chemotherapy and Targeted Therapy Combination). The clinical treatment started in July of 2010. The purpose of the treatment was to test the safety and feasibility of CART19 in relapsed/refractory B-cell neoplasms. Autologous T-cells were genetically modified using a lentiviral vector to express CD19-specific CAR. Some of the inclusion criteria were that patients had to be of sound body and health, express previous treatment failure, have autologous T-Cell availability to harvest the patients T-Cells, have adequate organ function, and the patient must have signed informed consent.

Figure 2:Panel A illustrates the lentiviral vector used to modify T cells for CART19 therapy, containing key functional elements for targeting CD19, while Panels B, C, and D show clinical data and imaging, including serum markers, bone marrow biopsies, and CT scans before and after treatment, highlighting tumor response and recovery.

Conclusion¶

The exploration of immunotherapy techniques, particularly through the use of Blinatumomab has shown great potential in treating patients with lymphocytic leukemia and can be another venue scientists and research approach how to address cancer. These trials not only state the efficacy of Immunotherapy techniques, they also underscore the importance of patient criteria in trials to get the most consistent data that correlates to the general human population. As these trials get to later phases and advance, the follow-up research will be a key to our understanding of this novice therapy that has the potential to cure most cancers. More research in different types of cancers and different strands of leukemia can be predicted for the near future as Blinatumomab is reaching greater strides in the battle against cancer.

Copyright © 2024 Edwin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, which enables reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the creator.

- ALL

- acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- CAR

- chimeric antigen receptor

- CLL

- chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- Pérez-Carretero, C., González-Gascón-y Marín, I., Rodríguez-Vicente, A. E., Quijada-Álamo, M., Hernández-Rivas, J.-Á., Hernández-Sánchez, M., & Hernández-Rivas, J. M. (2021). The Evolving Landscape of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia on Diagnosis, Prognosis and Treatment. Diagnostics, 11(5), 853. 10.3390/diagnostics11050853

- Sharma, S., & Rai, K. R. (2019). Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) treatment: So many choices, such great options. Cancer, 125(9), 1432–1440. 10.1002/cncr.31931

- Carballido, E., Veliz, M., Komrokji, R., & Pinilla-Ibarz, J. (2012). Immunomodulatory Drugs and Active Immunotherapy for Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Cancer Control, 19(1), 54–67. 10.1177/107327481201900106

- Wang, Z., Zhang, Z., Li, Y., Sun, L., Peng, D., Du, D., Zhang, X., Han, L., Zhao, L., Lu, L., Du, H., Yuan, S., & Zhan, M. (2021). Preclinical efficacy against acute myeloid leukaemia of SH1573, a novel mutant IDH2 inhibitor approved for clinical trials in China. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B, 11(6), 1526–1540. 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.03.005

- Eichhorst, B., Cramer, P., & Hallek, M. (2016). Initial therapy of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Seminars in Oncology, 43(2), 241–250. 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2016.02.005

- Porter, D. L., Levine, B. L., Kalos, M., Bagg, A., & June, C. H. (2011). Chimeric Antigen Receptor–Modified T Cells in Chronic Lymphoid Leukemia. New England Journal of Medicine, 365(8), 725–733. 10.1056/NEJMoa1103849

- Vincent, K., Roy, D.-C., & Perreault, C. (2011). Next-generation leukemia immunotherapy. Blood, 118(11), 2951–2959. 10.1182/blood-2011-04-350868

- Major, A., Yu, J., Shukla, N., Che, Y., Karrison, T. G., Treitman, R., Kamdar, M. K., Haverkos, B. M., Godfrey, J., Babcook, M. A., Voorhees, T. J., Carlson, S., Gaut, D., Oliai, C., Romancik, J. T., Winter, A. M., Hill, B. T., Bansal, R., Villasboas Bisneto, J. C., … Kline, J. (2023). Efficacy of checkpoint inhibition after CAR-T failure in aggressive B-cell lymphomas: outcomes from 15 US institutions. Blood Advances, 7(16), 4528–4538. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2023010016