Green synthesis of decomposing rubber; comparing processing using carboxymethyl cellulose and Ipomoea pes-caprae

Abstract¶

In recent years effort has been made to innovate alternative sustainable options to classic materials. Rubber is one of those materials that poses a major problem worldwide as it fills landfills, infiltrates ecosystems, and poses a threat to wildlife. Previous research that sought out to develop compostable or biodegradable plastics had found that CMC increases mechanical properties and decomposition in the production of biodegradable films, while CSG improves swelling and decomposition. In another study Ipomoea alba was used to cure LNR and it increased the material’s malleability and elasticity. The goal of this research was to develop a method of green synthesis of a latex natural rubber (LNR) material specific to the purpose of rubber band production with increased decomposability and a decreased negative impact on the ecosystem as well as minimized cost. To accomplish this, the LNR was combined with a solution of cassava starch and glycerol (CSG). The study also compared the qualities of LNR/CSG material processed using Carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) with LNR processed using an extract from the Ipomoea pes-caprae vine (IPC), native to North Carolina. Additionally, it examined how different ratios and concentrations of Cassava Starch Glycerol (CSG) solution affected the properties of LNR samples.This study confirmed that processing a CSG and LNR material with CMC increases its solubility and it additionally discovered that it also increases its uniformity. It also found that levels of CMC are directly proportional to percent mass loss, and CMC enhances elastic properties of the CSG/LNR material due to its high interfacial crosslinking capacity with starch. Additionally, increasing [CSG] (from 10 to 15) did not show positive solubility patterns between samples of the same ratios, and increasing the viscosity of the solution decreased mechanical properties immensely. Notably, the IPC extract had effects on the LNR material similar to those caused by processing using Ipomoea alba vine extract in a previous study. It greatly improved the mechanical elastic properties of the CSG/LNR material and the material cohered more when twisted and was malleable when heated. Processing utilizing a combination of IPC and CMC resulted in a rigid material with low flexibility. Consequently, the most optimal ratio for a rubber band material that balances decomposition and mechanical properties was found to be 60:40:15 of CSG (10%):LNR:CMC.

Introduction¶

In 2018 the U.S. produced 9.2 million tons of rubber waste (Chittella et al. (2021)), and the rates are only increasing with the rise in population and production. This rubber waste poses a huge threat to native wildlife and ecosystems. On an isolated UK island, huge amounts of rubber bands and fishing nets have been found in the undigested pellets of sea birds who mistake them for worms (Prior (2019)). Due to the vulcanization process that it undergoes, recycling rubber is extremely demanding. Vulcanized rubber also displays great resistance to decomposition due to the presence of highly hydrophobic cross-linked structures, provided by certain additives and the vulcanization process itself.

Vulcanization is the process through which latex natural rubber (LNR) is mixed with curing agents (which induce crosslinking of the polymer chains creating a tight molecular network) and then heated to solidify the overall polymer structure. Vulcanized products have greater retractile properties – increased elasticity and decreased plasticity under a greater range of changes in temperature and wear. Most common-day materials are only mildly vulcanized. Sulfur is the most commonly used crosslinking agent but its downside is that it requires toxic and expensive activators and accelerators (Freudenrich (1970)) and it combusts into the highly toxic sulfur dioxide.

A previous study set out to increase biodegradability, reduce cost, and improve the mechanical properties of Polylactic acid using a mixture of pineapple stem starch and modified natural rubber (Tessanan et al. (2024)). Starch is a low-cost, renewable, biodegradable, and highly-available substance. It increases the swelling of the material in moist conditions and has been proven to lead to weight loss during degradation. Starch also has a high amylose content which drives the growth of beneficial microbes that feed on it (New study reveals waxy starches in sorghum have negative impact on gut microbiome (2023)), metabolizing the material, consequently breaking it down and promoting biodegradability. Simultaneously, using starch in rubber materials unfortunately reduces the tensile strength and water-resistant properties of the polymer, therefore glycerol can be used as a plasticizer to improve the flexibility and processing ability of the starch (Leksawasdi et al. (2021)).

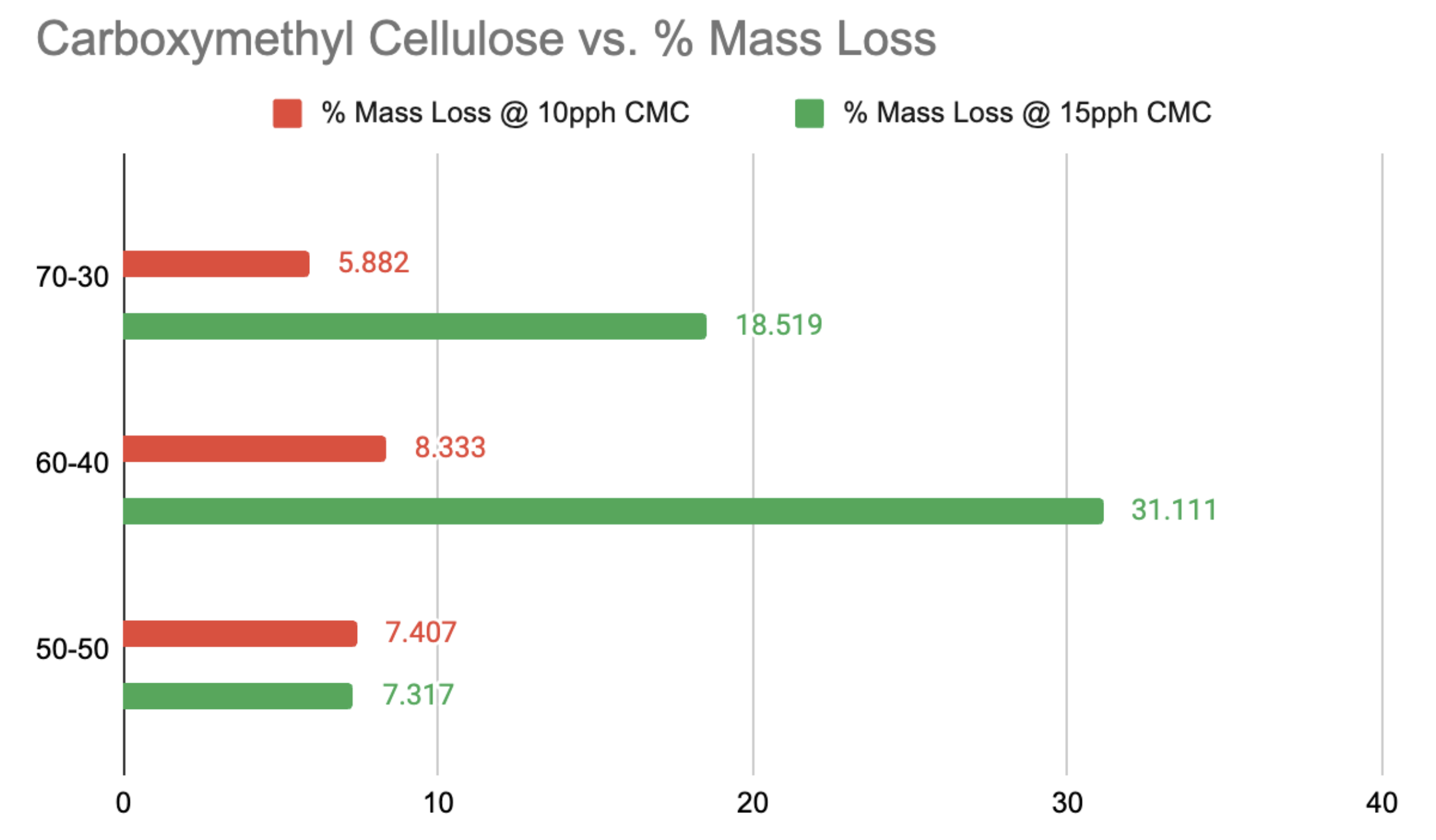

Another study, by Leksawasdi et al. (2021), developed biopolymer films using reactive blending of corn starch and glycerol (CSG), latex natural rubber (LNR), and carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC). CMC is a cellulose derivative obtained from alkali cellulose and sodium salt reactions. CMC can be prepared using a wide variety of organic products and industrial waste (Wongvitvichot et al. (2021)), and it is non-toxic. CMC was used as a crosslinking agent because it is highly compatible with starch, carboxylic groups, and sodium ions – therefore structurally similar to CSG. It increases interactions between hydroxide groups, connecting the CSG (hard phase) and LNR (elastic phase) which improves the mechanical properties of the blend and increases elongation at the break, max tensile strength, and Young’s modulus.

Additionally, due to swellable content and effective interfacial crosslink density of CSG/LNR through the reaction mechanism of CMC, CMC can increase the solubility of the CSG/LNR/CMC blend. Yet, at too high of a concentration, the CMC forms a dense interfacial crosslinking with LNR, so it is crucial to find the right balance.

This study developed a tough, transparent, water-resistant, biodegradable material with high tensile properties. In this case, the purpose of the material was packaging, hence, it was thin and film-like. My study will work on discovering an optimal ratio of starch to glycerol to CMC for a thicker material that can be used for rubber bands; it will also utilize cassava starch instead of cornstarch, because of its high purity and chemical modification abilities.

Although the process of rubber making can involve much chemical refinement, the craft originates from ancient Mesoamericans, who created it using the Castilla elastica and the Ipomoea alba plants. I.alba vine extract purifies the natural rubber latex by phase separation. It concentrates and removes proteins (plasticizing agents), and its oil content induces latex coagulation (behaves better with the whole vine extract). Natural Latex Emulsion consists of three phases: a cis-1,4-polyisoprene phase, an aqueous phase, and insoluble components, such as plasticizers, which reduce viscosity by disrupting interactions between polymer chains. Treatment of suspension with I. alba vine extract destabilizes the emulsion, separates the polymer and aqueous phases (a process called coagulation), and solubilizes plasticizing agents, allowing chain entanglement and interchain interactions. The resulting coagulated solid is amorphous except for some crystalline material which improves the mechanical properties as a non-covalent crosslinker.

Multiple spectroscopy tests identified aliphatic methyl and methylene groups and indicated the presence of sulfonyl chloride and sulfonic acid moieties in the I.alba vine extract. These sulfur-containing organic groups are capable of reacting with the alkenes in the polymer chain, and a bifunctional molecule could act as a cross-link. Sulfonyl chlorides and sulfonic acids are also known to induce cyclization of 1,4-polyisoprene, which introduces rigid segments into the polymer chain. A small number of these segments would have the same effect on elastic behavior as cross-links and would consequently increase elasticity. Overall the plant increased stiffness and the degree of interchain interactions in the processed rubber, which could have been introduced by covalent cross-linking or by noncovalent interactions (Hosler et al. (1999)).

My study aims to determine whether other plants from this genus, such as the Ipomoea pes-caprae have the same coagulating, elastic, and flexibility-increasing properties.

In the past, the investigations towards a more sustainable future in rubber production were centered around two main groups of study: (1) improving performance while ensuring sustainability, or (2) improving properties of biodegradability. Most studies do not discuss both factors in relation to each other, but that is the challenge this project undertook.

Methods of Preparation¶

Derivation of Vine Extract from Ipomoea pes-caprae¶

Within a few minutes of cutting, strip the plant of leaves and flowers, leaving only the vine. Crush the vine using a mortar and pestle to squeeze as much juice out as possible. After the most possible amount has been extracted, add silicon sand to aid with grinding. Centrifuge at 10000 rpm for 5 min.

Preparation of Rubber Samples¶

To synthesize the rubber samples, latex natural rubber (LNR), cassava starch glycerol solution (CSG), along with the processing agent of either carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC), extract from the Ipomoea pes-caprae vine (IPC), or both were combined utilizing the method of melt blending. The 10% CSG solution was prepared by combining 7 g of cassava starch (CS) with 3 g of 99% glycerol in 100 ml of deionized water in a capped 125 ml Erlenmeyer flask and heated in a water bath at a temperature of 50 ℃ for 30 minutes, utilizing a magnetic stir bar to keep solution agitated evenly. The 15% CSG solution was prepared via the same method but with 10.5 g of CS and 4.5 g of glycerol. To make a CSG solution of a viscous homogeneous consistency the parameters change to heating at 80 ℃. The CSG solution was then drawn using a plastic cuvette and transferred to 25–50 ml beakers to be combined with LNR at the given ratio. A CMC gel was prepared by heating a ratio of 1 g/ 10 ml DI water at 80 ℃ for 10 minutes in a 25 ml Erlenmeyer flask and stirring periodically. For samples utilizing CMC as a processing agent, the gel was drawn using a plastic cuvette and squeezed into the individual beaker samples of LNR/CSG. The same action was performed for samples utilizing IPC vine extract, which was previously centrifuged at 10000 rpm, as a processing agent. In both cases, the beaker was placed over a simmering water bath and all of the components were stirred together till evenly combined and warm.

Heat Processing¶

The CSG/LNR/CMC and CSG/LNR/IPC and CSG/LNR/CMC/IPC solutions were poured into previously prepared and dried metal forms (4.80 cm x 3.60 cm x 1.70 cm) glued to a baking sheet using leftover CMC solution. The samples were then heat processed in the muffle furnace at their respective temperatures. The researcher created samples at various ratios of component ingredients. They are demonstrated in Table 2- Table 5. The concentration ratios were narrowed down to the most optimal ones through the testing of samples with modified variables.

Debubbling¶

Two methods of debubbling were attempted. The first used a small heat gun on the unbaked form-poured samples. The second consisted of putting the form-poured samples into a sealed bell jar connected to a vacuum for 2-5 minutes, or till the amount of apparent bubbles in the sample was minimized and the surface was glossy and smooth, without the sample boiling over due to the excessive decrease in pressure.

Methods of Testing¶

Solubility¶

The solubility of the samples was used as a guiding factor to help indicate the possible biodegradability of a given sample of rubber. The researcher prepared samples of equal dimensions (4.50 cm x 0.875 cm x ~0.10 cm) and measured their initial mass. They were submerged in 50 ml of DI water and shaken at 35 rpm for 24 hours. After the samples had dried completely, their mass was recorded again. Percent mass loss, or solubility, was calculated using the following formula:

Where %ML is the percent mass loss, Mi, is the initial mass, and Mf is the final mass.

Mechanical Properties¶

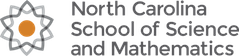

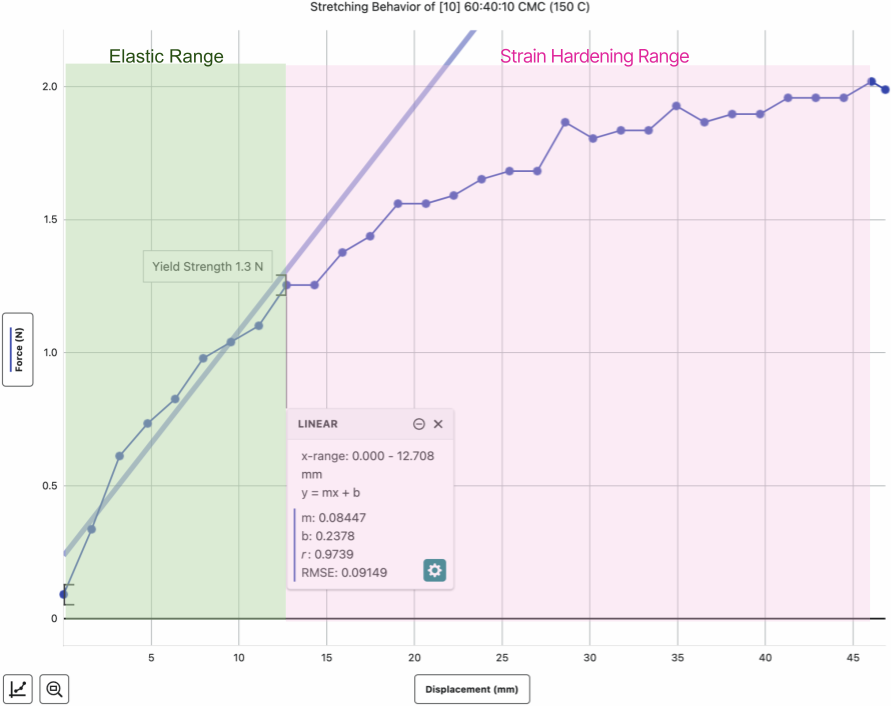

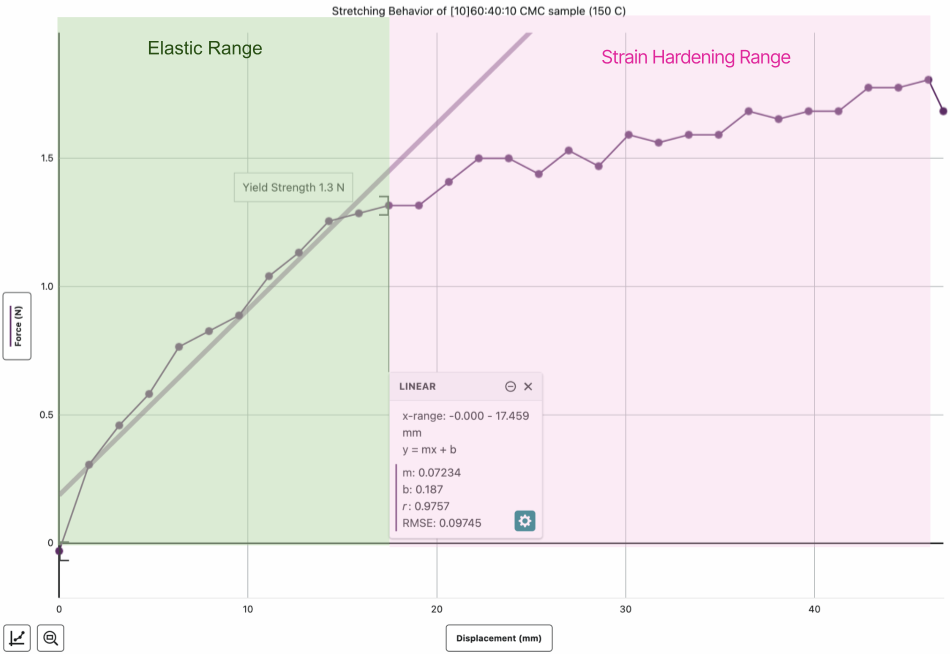

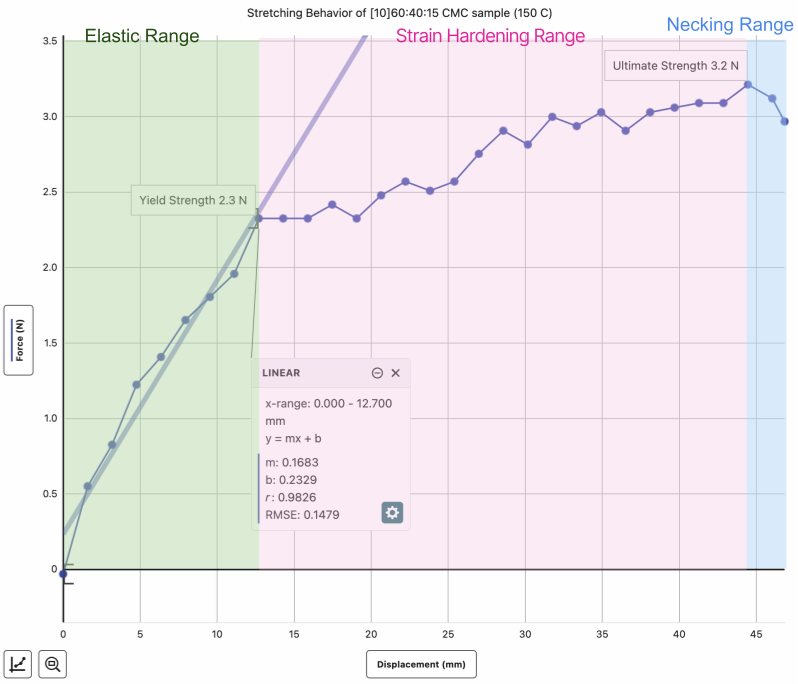

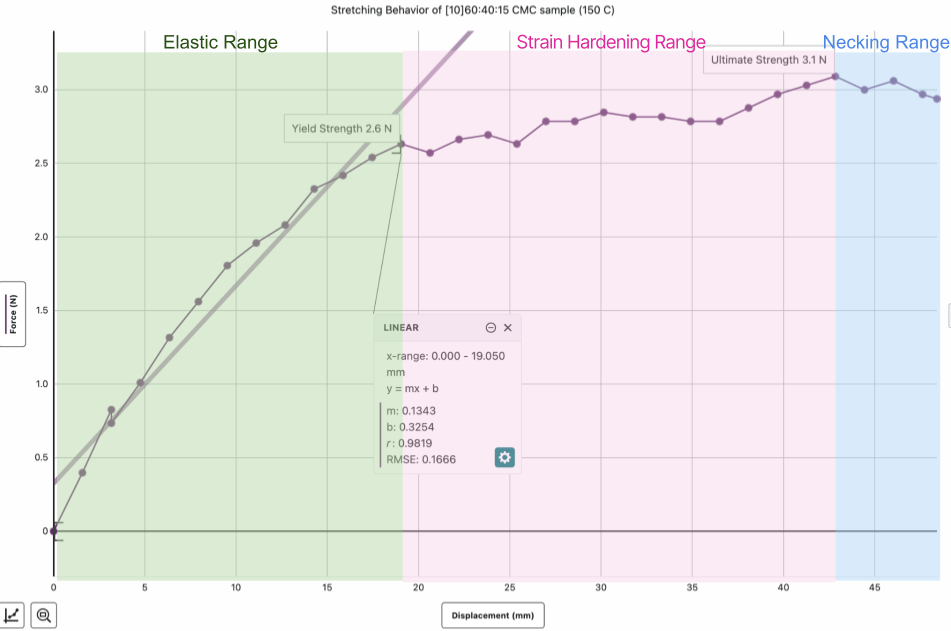

A modified Vernier Structures and Materials tester was utilized to observe patterns of elasticity. Values for displacement and force were recorded as coordinate pairs for every turn of the wheel. Although this machine is not as accurate as industrial lab-grade tensile testing machines, it was possible to create a stress-strain curve and point out the regions of elasticity, strain hardening, and necking (Figure 1). By applying a linear curve fit on the elastic range, it was possible to find a Young’s modulus value that could be compared between experimental samples to aid in the analysis of their elasticity. Qualitative analysis was the primary method used to determine the mechanical merits of the material. Factors that the researcher considered included the formation of rips and cracks, elongation at break, brittleness, holes in the material, surface regularity, and how well the species retained its original length.

Figure 1:(Young's modulus (2025)): Example of Stress-Strain Curve

Melting¶

Rectangular samples of rubber were placed between two pieces of aluminum foil on a hot plate for 10 minutes at each of the following temperatures: 100 ℃, 160 ℃, 200 ℃. Their qualitative properties of malleability, cohesiveness, and melting point were observed and recorded.

Discussion and Analysis¶

Percentages of solubility of all samples are displayed in Table 1 - Table 5 below.

Table 1:CMC processed rubbed at 80 ℃ for 18 h

| CSG Concentration | CSG % | LNR % | CMC pph | Initial Mass (g) | Mass After Dissolving (g) | Percent Loss % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 90 | 10 | 10 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 25 | |

| 10 | 80 | 20 | 10 | 0.12 | 0.1 | 16.66666667 |

| 10 | 70 | 30 | 10 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 5.882352941 |

| 10 | 60 | 40 | 10 | 0.24 | 0.22 | 8.333333333 |

| 10 | 50 | 50 | 10 | 0.27 | 0.25 | 7.407407407 |

| 10 | 40 | 60 | 10 | 0.2 | 0.18 | 10 |

| 10 | 30 | 70 | 10 | 0.34 | 0.32 | 5.882352941 |

| 10 | 20 | 80 | 10 | 0.4 | 0.38 | 5 |

| 10 | 0 | 100 | 10 | |||

| 10 | 70 | 30 | 15 | 0.27 | 0.22 | 18.51851852 |

| 10 | 60 | 40 | 15 | 0.45 | 0.31 | 31.11111111 |

| 10 | 50 | 50 | 15 | 0.41 | 0.38 | 7.317073171 |

| 15 | 60 | 40 | 15 | 0.32 | 0.27 | 15.625 |

| 15 | 40 | 60 | 15 | 0.4 | 0.37 | 7.5 |

| 15 | 40 | 60 | 0 |

Table 2:IPC processed rubber at 80 ℃ for 18 h

| CSG Concentration | CSG % | LNR % | IPC pph | Initial Mass (g) | Mass After Dissolving (g) | Percent Loss % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 60 | 40 | 10 | 0.184 | 0.16 | 13.04347826 |

| 10 | 60 | 40 | 10 | 0.255 | 0.226 | 11.37254902 |

| 10 | 60 | 40 | 0 | 0.306 | 0.2782 | 9.08496732 |

| 10 | 60 | 40 | 0 | 0.258 | 0.2326 | 9.84496124 |

Table 3:CMC processed rubber 150 ℃ 15 min

| CSG Concentration | CSG % | LNR % | CMC pph | Initial Mass (g) | Mass After Dissolving (g) | Percent Loss % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 60 | 40 | 15 | 0.251 | 0.2175 | 13.34661355 |

| 10 | 60 | 40 | 15 | 0.35 | 0.3017 | 13.8 |

| 10 | 60 | 40 | 10 | 0.315 | 0.2712 | 13.9047619 |

| 10 | 60 | 40 | 10 | 0.212 | 0.1825 | 13.91509434 |

| 10 | 60 | 40 | 0 | 0.306 | 0.2782 | 9.08496732 |

| 10 | 60 | 40 | 0 | 0.258 | 0.2326 | 9.84496124 |

Table 4:IPC processed rubber 150 ℃ 15 min

| CSG Concentration | CSG % | LNR % | IPC pph | Initial Mass (g) | Mass After Dissolving (g) | Percent Loss % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 60 | 40 | 10 | 0.189 | 0.1629 | 13.80952381 |

| 10 | 60 | 40 | 10 | 0.219 | 0.1927 | 12.00913242 |

Table 5:ICMC and IPC processed rubber 150 ℃ 15 min

| CSG Concentration | CSG % | LNR % | CMC pph | IPC pph | Initial Mass (g) | Mass After Dissolving (g) | Percent Loss % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 60 | 40 | 10 | 10 | 0.325 | 0.2829 | 12.95384615 |

| 10 | 60 | 40 | 10 | 10 | 0.379 | 0.3247 | 14.32717678 |

Tensile strength testing found that increasing the concentration of LNR –simultaneously decreasing the watery CSG– leads to a denser, stiffer material and decreases solubility because more polymer molecules and less starch and moisture intercepting the web creates a denser polymer structure. Experiments have also shown that the material samples processed with the agitated watery consistency CSG displayed far better mechanical properties than those processed with the viscous, homogenous CSG. The watery CSG created smooth, elastic, and more tear-resistant material, while the viscous CSG created a highly brittle, leather-like material that tore easily (Figure 2). Although the solubility was increased in the viscous CSG sample, the improvement was insignificant considering the tremendous compromise to the quality of mechanical properties. Further increase of the concentration of CSG from 10% to 15% did not show a positive behavior pattern concerning solubility and mechanics between samples of otherwise identical ratios. This may be due to the decreased interfacial interaction between the LNR and CSG.

Figure 2:LNR sample processed using viscous CSG

It was also discovered that materials processed using I. pes-caprae vine extract displayed similar behaviors to those processed with I.alba vine extract. When processed at a low heat of 80 ℃ for 18 hours, the rubber samples displayed patterns of improved elasticity and adhered to themselves minimally when twisted – a behavior caused by the lack of a fully crosslinked network. When heated during melt testing, the material was somewhat malleable at temperatures between 100 ℃ - 200 ℃. When samples of the same ratios were processed at an increased heat of 160 – 200 ℃ for 20 min, their mechanical properties decreased tremendously to a low elongation at break. This may be due to the organic matter from the plant extract burning within and creating microscopic holes in the process.

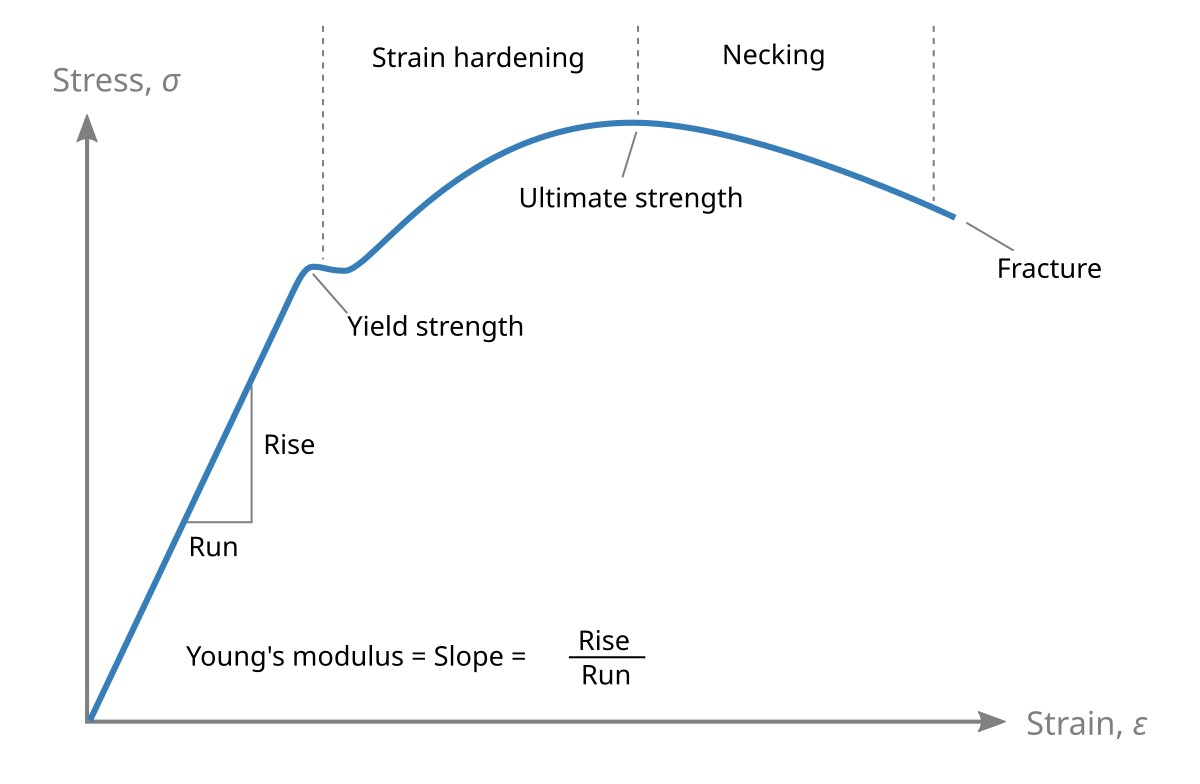

The data collected during testing, displayed in Figure 3, demonstrates that increasing pph of CMC from 10 to 15 displayed trends of either largely improved solubility or minimal change in solubility between samples of the same ratio. Samples of CSG/LNR processed with CMC displayed increased solubility and swelling due to the increase in the interfacial crosslink density of CSG/LNR through the CMC reaction mechanism (Leksawasdi et al. (2021)). Although normally a higher density would prevent the penetration of water and decrease solubility, in this case, because CSG and the CMC gel are both hydrophilic, their interference in the polymer network draws water in making it swell and creating gaps in the structure, which helps it break down. By this crosslinking mechanism, CMC also makes the material more elastic and uniform. There is also crosslinking within the CMC phase itself. Its Na+ ions, from its synthesis process, form physical crosslinks with the carboxylic acid groups (Figure 4).

Figure 3:Comparison of mass loss between LNR samples processed with a higher and a lower concentration of CMC

Figure 4:(NMR Chemical Shifts of Impurities (n.d.)): Lewis Structure of carboxymethyl cellulose

Changing the heat processing conditions from 18 h at 80 ℃ to 15 min at 150 ℃, and afterward leaving them to dry, improved the mechanical properties of the samples processed with CMC. The reason for this pattern could be that the higher temperature allows more bonds to form as the bond enthalpy is reached. Higher temperatures also catalyze reactions allowing for more reactions to occur. This finding is significant as this method would expedite the process and lower energy consumption, making the process greener.

The results of CSG/LNR material processed with a combination of CMC and IPC were largely negative. The material was very hard and brittle, with minimal elasticity, and an almost minimal elongation at break (Figure 5). It is important to note that this is largely the result of the high temperature that the sample was baked at (which in the IPC-only sample also resulted in negative results), but additionally, the inclusion of both processing agents might have created too dense of a crystalline structure between the polymers of polyisoprene, resulting in the rigidity of the material.

Figure 5:LNR processed with a combination of CMC and CSG

In the 60:40:CMC sample of CSG:LNR:CMC where the concentration of CSG was 10%, it was observed that increasing the concentration of CMC from 10 pph to 15 pph was correlated with a minimally decreased solubility (Table 3), but a positively increased Young’s Modulus, yield strength, and superior mechanical properties. The stretching behaviors of two samples of each of the two ratios are displayed in Figure 6- Figure 9. Young’s Modulus increased from an average of 0.07841 N/mm to an average of 0.1513 N/mm, and yield strength increased from 1.3 N to an average of 2.45 N between the CSG:LNR:CMC samples of 60:40:10 and 60:40:15 accordingly. Although both of the samples, 60:40:10 and 60:40:15 baked on an aluminum surface at 150 ℃ for 15 min and previously debubbled possessed excellent mechanical properties, the latter sample had a significantly greater elongation at break and did not develop any tears or holes (Figure 10).

Figure 6:Stress-strain curve of [10]60:40:10 (150℃) sample

Figure 7:Stress-strain curve of [10]60:40:10 (150℃) sample

Figure 8:Stress-strain curve of [10]60:40:15 (150℃) sample

Figure 9:Stress-strain curve of [10]60:40:15 (150℃) sample

Figure 10:Lack of noticeable tears and holes in [10]60:40:15 (150℃) sample

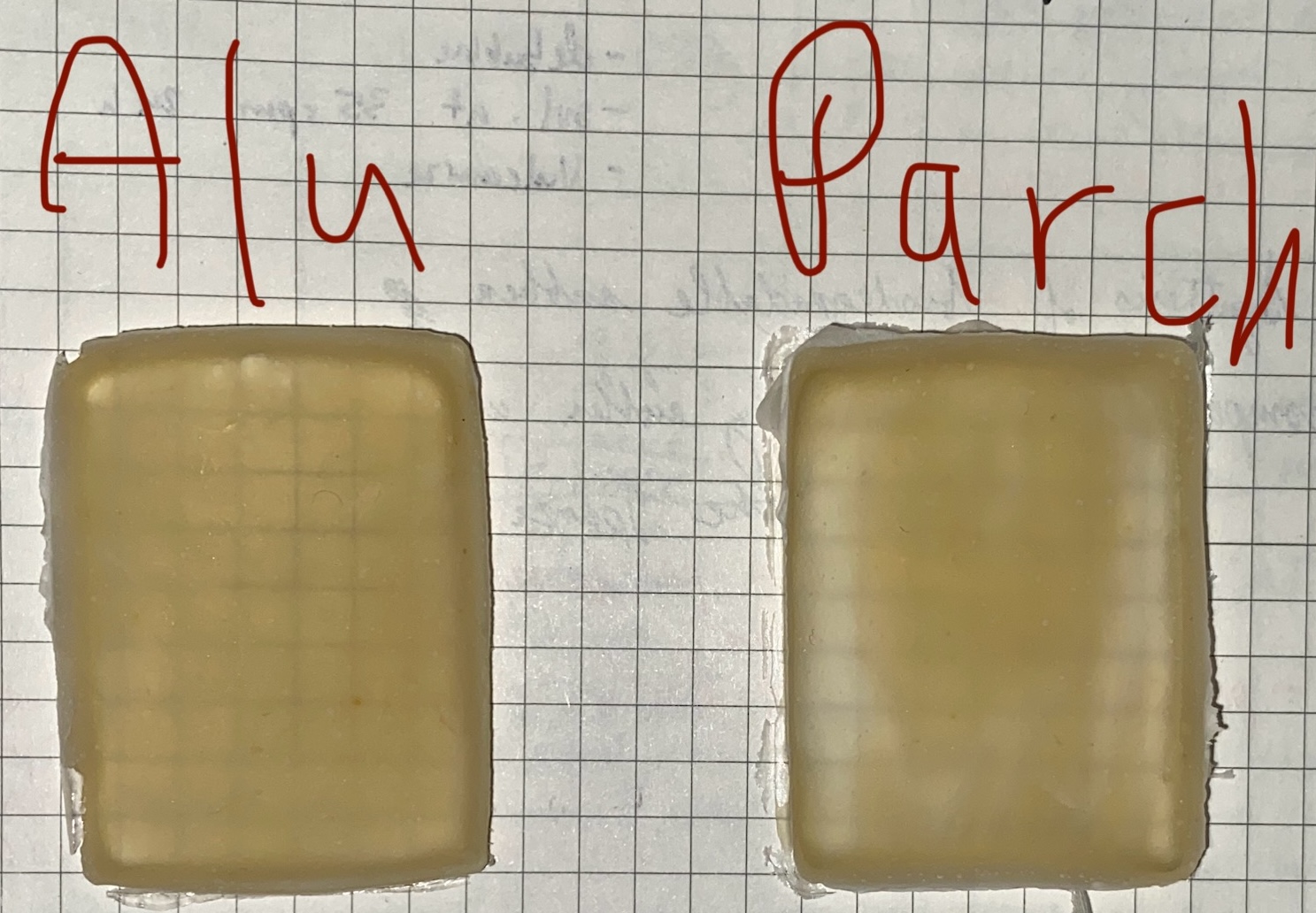

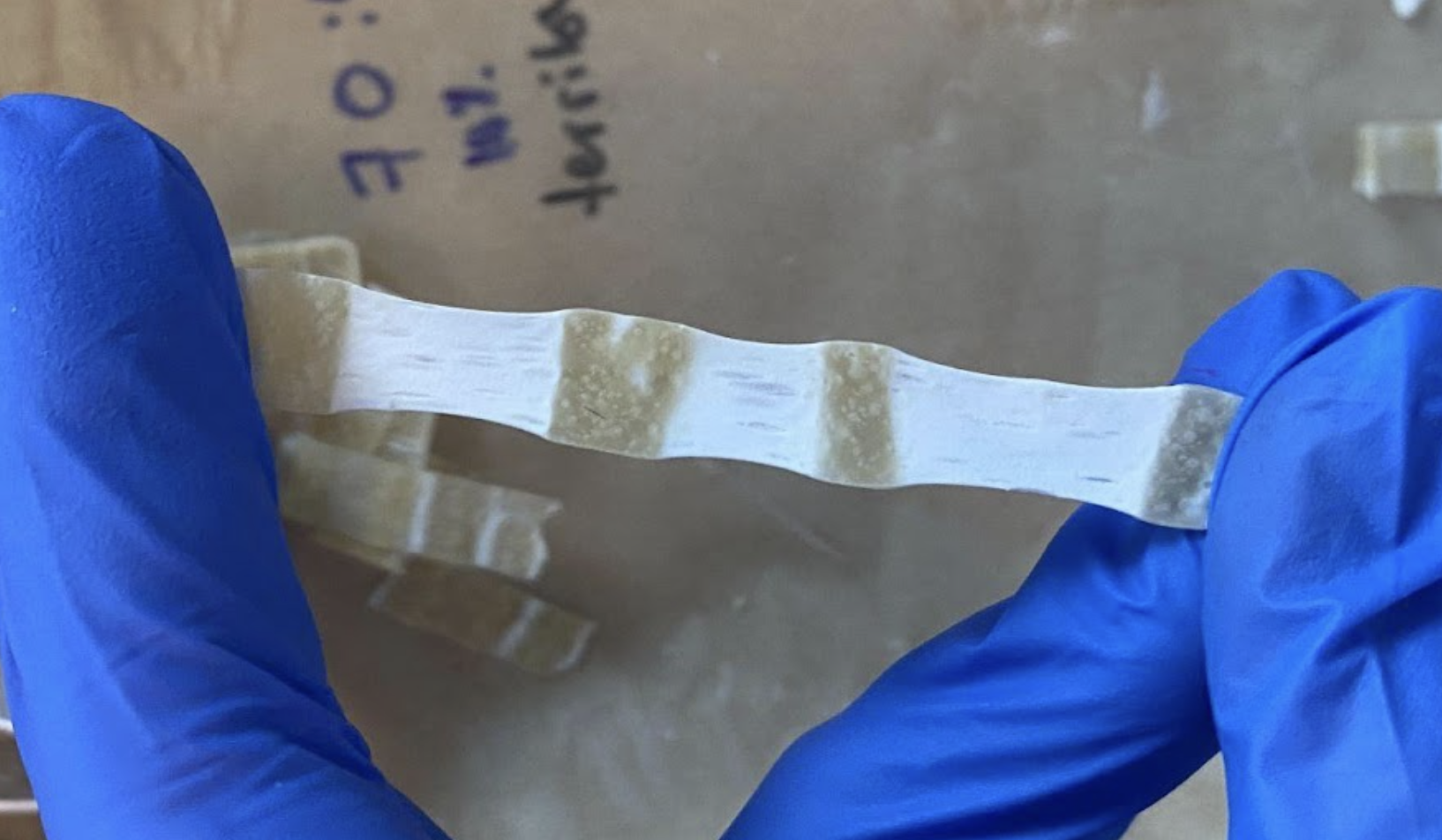

The experiments also showed that objectively minor adjustments in methodology provide significantly improved results. Debubbling using a bell jar proved to be an efficient way of getting rid of bubbles in the liquid samples before heat-processing them, which resulted in a baked and dried material with minimal holes/gaps, which in turn improved the mechanical properties of the material, namely elongation at break and tear resistance. Meanwhile, baking samples on a surface of aluminium resulted in samples with a smooth and even surface (Figure 11), which also improved their mechanical properties significantly, compared to the samples baked on parchment paper which resulted in ridges that caused an uneven distribution of tension when stretched (Figure 12), which in turn decreased the tensile strength and elongation at break.

Figure 11:LNR baked on aluminum sheets vs. parchment paper

Figure 12:Uneven tensile distribution observed in LNR samples baked on parchment paper

Conclusion¶

This study found that Carboxymethyl cellulose functions strongly as a processing agent for biodegradable rubber by acting as a compatibilizer with starch and strengthening its properties, which in turn aids in the breakdown. CMC itself also improves the mechanical properties of the material due to its surface-exclusive crosslinking capacity. A concentration of 15 pph provided the most optimal quality, elasticity, and elongation at break. The addition of cassava starch to rubber blends in combination with glycerol and carboxymethyl cellulose improved the material’s solubility significantly while maintaining its mechanical properties due to CMC’s tensile capacities. It was also discovered that Ipomoea pes-caprae in the rubber blend displays similar attributes, such as increased elasticity and malleability, to the ancient Mesoamerican rubber blends which included Ipomoea alba.

The study succeeded in creating a material that displays patterns of potential biodegradability and has the mechanical properties and endurance required for the production of rubber bands.

In the future, full biodegradability tests will need to be conducted over several months in organic matter containing microorganisms under a variety of changing conditions (turbulency, moisture, temperature, etc.) to truly see the full spectrum of the potential that this material has in the field of green materials chemistry and its ecological applications. FTIR and NMR spectroscopy of the samples will also need to be conducted to see how the molecular structures are impacted by the addition of the processing agents – what bonds are formed. Another potential test to determine the quality of solubility of the samples would be UV-vis spectroscopy of the solution that the samples dissolved in to see how the concentration of latex content in the solution changed. It will also be insightful to conduct testing on a higher quantity of samples and compare properties of synthesized samples to those of commercial rubber band products.

Special thanks to Dr. William Grubbs for his support and supervision throughout the project, as well as Mr. Adam Benoit for recommending me to use a bell jar.

Copyright © 2024 Mikolajec. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, which enables reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the creator.

- CMC

- Carboxymethyl cellulose

- CS

- Cassava starch

- CSG

- Corn starch and glycerol

- IPC

- Ipomoea pes-caprae vine

- LNR

- Latex natural rubber

- Chittella, H., Yoon, L. W., Ramarad, S., & Lai, Z.-W. (2021). Rubber waste management: A review on methods, mechanism, and prospects. Polymer Degradation and Stability, 194, 109761. 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2021.109761

- Prior, R. (2019). Why sea birds regurgitated thousands of rubber bands on an uninhabited British island. In CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2019/10/23/world/sea-birds-worms-scn-trnd/index.html

- Freudenrich. (1970). How Rubber Works. In HowStuffWorks. https://science.howstuffworks.com/rubber.htm

- Tessanan, W., Phinyocheep, P., & Amornsakchai, T. (2024). Sustainable Materials with Improved Biodegradability and Toughness from Blends of Poly(Lactic Acid), Pineapple Stem Starch and Modified Natural Rubber. Polymers, 16(2), 232. 10.3390/polym16020232

- New study reveals waxy starches in sorghum have negative impact on gut microbiome. (2023). Gut Microbes, 15(1), 2178799. 10.1080/19490976.2023.2178799

- Leksawasdi, N., Chaiyaso, T., Rachtanapun, P., Thanakkasaranee, S., Jantrawut, P., Ruksiriwanich, W., Seesuriyachan, P., Phimolsiripol, Y., Techapun, C., Sommano, S. R., Ougizawa, T., & Jantanasakulwong, K. (2021). Corn starch reactive blending with latex from natural rubber using Na+ ions augmented carboxymethyl cellulose as a crosslinking agent. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 19250. 10.1038/s41598-021-98807-x

- Wongvitvichot, W., Pithakratanayothin, S., Wongkasemjit, S., & Chaisuwan, T. (2021). Fast and practical synthesis of carboxymethyl cellulose from office paper waste by ultrasonic-assisted technique at ambient temperature. Polymer Degradation and Stability, 184, 109473. 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2020.109473

- Hosler, D., Burkett, S. L., & Tarkanian, M. J. (1999). Prehistoric Polymers: Rubber Processing in Ancient Mesoamerica. Science, 284(5422), 1988–1991. 10.1126/science.284.5422.1988

- Young’s modulus. (2025). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Young%27s_modulus&oldid=1282966396

- NMR Chemical Shifts of Impurities. (n.d.). In Sigma Aldrich. https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/MX/en/technical-documents/technical-article/genomics/cloning-and-expression/blue-white-screening