A Novel Approach to Inhibit MAP2K1 Overexpression Present in Melorheostosis Utilizing Moringa oleifera Extracts

Abstract¶

Melorheostosis is a rare bone disorder characterized by a mutation in the MAP2K1 gene in the MAPK signaling pathways, overproducing MEK1 protein, resulting in abnormal, flowing bone growth. Treatment and diagnosis options are limited; therefore, this experiment explores the use of Moringa oleifera, a promising natural product, as a potential treatment option for melorheostosis. In this experiment M. oleifera seed and leaf extract was fed to Drosophila melanogaster and DSOR1 protein (an ortholog of the MEK1 protein) was extracted from samples and examined through a western blot. However, experimental results were inconclusive due to technical issues in the western blotting process. This paper serves as a novel method to study MEK1 protein expression in humans through the use of D. melanogaster and natural product chemistry. Future research possibilities include rerunning the western blot and optimizing the conditions, testing the synergistic effects of leaf and seed extracts, and investigating moringin (an isothiocyanate found in M. oleifera leaves).

Introduction¶

Being derived from the Greek words “melos,” which means limbs, “rheos,” which means to flow, and “ostosis,” which relates to bone formation, melorheostosis often results in a “flowing” pattern of excess bone growth along any body part. This is often compared to candle wax melting off of a candlestick, which gives this condition the nickname “dripping candle wax disease.” Melorheostosis is a rare and relatively unexplored bone disorder characterized by irregular and asymmetrical bone growth atop the long bones of a patient’s upper and lower limbs. Symptoms stemming from abnormal bone development include joint pain, stiffness, soft tissue fibrosis, and lesions 10 Fick et al., 2019. Furthermore, with merely 300 reported cases worldwide leading up to 2015, the diagnosis and treatment options haven’t been thoroughly researched and understood Vyskocil et al., 2015.

However, recent research has proposed a potential answer for the previously unknown cause of melorheostosis. From biopsies taken from 15 melorheostosis patients, 8 exhibited a mutation in the MAP2K1 gene Kang et al., 2018. MAP2K1 encodes proteins that are part of the RAS/MAPK signaling pathway. Further research showed that a somatic mutation of the MAP2K1 oncogene causes the overproduction of the specific MEK1 protein, which affects human bone formation. The enhanced MEK1 activity surrounding abnormal mutations supports MAP2K1’s involvement in melorheostosis. Since MAP2K1 and MEK1 are part of a signaling pathway associated with cellular proliferation, a somatic mutation causes an excess quantity of the MEK1 protein. This then results in excess cellular proliferation. This cellular proliferation takes the form of excess candle wax-like growth.

Even though researchers have potentially found a cause, treatment options are severely limited, with surgery being one of the only options for many Chou et al., 2012. Apart from surgery, synthetic drugs are in development that try to combat melorheostosis, but their long-term efficacy is questionable and currently untested. By branching out into the field of natural product chemistry, a concrete treatment option can be derived. Natural product drugs have an advantage over synthetic drugs by containing bioactive compounds that can attack many biological targets. They also are correlated with decreased preclinical toxicity Stratton et al., 2015. With the advantages of natural product chemistry, it is evident that it can be a viable melorheostosis treatment option.

A significant challenge is finding the right natural product to combat the rapid cell proliferation associated with a MAP2K1 mutation in melorheostosis. For thousands of years, a medicinal plant from South Asia has been used as a natural drug for various medical conditions and can be used to combat melorheostosis. Moringa oleifera is a fast-growing, deciduous tree primarily grown in India and Bangladesh and has been a staple of regional medicine since the Roman Empire. The roots, leaves, and bark are all utilized to create pastes, powders, and concoctions to treat conditions such as malaria, arthritis, skin lesions, and diabetes Chiș et al., 2023. Due to its medicinal benefits, it has nicknames such as the “miracle tree” and “mother’s best friend.” Similar to other plants, Moringa oleifera is full of bioactive compounds such as flavonoids and phenolic compounds. However, with it only growing in hot climates, Moringa oleifera’s medicinal potential hasn’t been recognized worldwide.

Yet in recent years, researchers have been testing the various properties of the plant to see its effective bioactive compounds regarding diabetes, cancer, and other major diseases. Studies have also shown a significant difference in the medicinal properties of extracts from different parts of the plant. Leaves tend to have better antimicrobial and antidiabetic properties, while roots have better antioxidant properties Tshabalala et al., 2020. Not only does Moringa oleifera contain antioxidant, antidiabetic, and antimicrobial compounds, but it has also shown promising inhibitory properties concerning cancer. There are now ten known compounds that have the potential for anticancer substances. These compounds induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, which are useful for suppressing mutations and excess cell proliferation Wisitpongpun et al., 2020. This leads to the question of whether Moringa oleifera could be useful in inhibiting the gene expression and production of MEK1 to stop the excess bone growth associated with melorheostosis. The purpose of this research is to effectively extract bioactive compounds from Moringa oleifera leaves and seeds to test their inhibitory effects on the MAP2K1 oncogene and the MEK1 protein in Drosophila melanogaster (fruit fly) to justify its use in melorheostosis treatment. A fruit fly model is used due to the fact that they contain the DSOR1 gene, which produces MEK1 protein within fruit fly tissue. Since DSOR1 is an ortholog for the MAP2K1 gene, inhibiting expression in fruit flies will be an accurate model for inhibiting MAP2k1 expression in humans.

Methods¶

Collection of Leaf and Seed Samples¶

Moringa leaves were collected in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina. The samples were collected from a potted, young M. oleifera plant on 3 different dates. The first sample was collected on August 12, 2023, the second was collected on September 3, 2023, and the third sample was collected on September 9, 2023. Each sample contained 50g of leaves cut with scissors and placed in a sterile plastic bag. Each sample was frozen overnight, and transported to Burke County, North Carolina in an insulated container with a temperature of 0°C. At the lab, leaves were stored in a freezer at -18°C.Seeds had been collected in Mexico and were ordered from Yerbero. Seed samples were ordered on June 15, 2023, and were stored at room temperature until usage.

Preparation of Leaf Extract¶

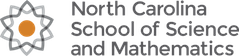

Leaves were frozen at least 24 hours before the procedure. Using an oven, the leaves were heated at 50°C for 2 hours and left to dry overnight at room temperature. 20g of dried leaves were crushed using a coffee grinder until they became a fine powder. This fine powder was then extracted at room temperature utilizing a sequence of three solvents in increasing polarity: hexane, methanol, and water. 200 mL of each solvent was used, and each solvent was extracted for 2 and a half hours. After each solvent was extracted for this interval, they were each filtered and evaporated in vacuo. 0.7g of crude extract was gained. The experiment was repeated 2 times to obtain a total of 2.1g of evaporated leaf extract. This mass was then dissolved in 50 mL of bottled spring water.

Figure 1:Preparation of Crude Leaf Extract Using Rotary Evaporator

Preparation of Seed Extract¶

Using an oven, the seeds were heated at 50°C for 3 hours and continued to dry overnight at room temperature. Wings and shells were removed from the seeds and discarded. 20g of dried seeds were crushed into a fine powder with a coffee grinder and extracted in 1 L of hexane overnight. Hexane extract was filtered and evaporated in vacuo. The extract was transferred into 50 mL of water for 48 hours and evaporated in vacuo after the 48-hour interval. Approximately 0.8g of crude seed extract was collected. The experiment was repeated 2 times to obtain 2.4g of extract. This mass was mixed into 50 mL of bottled spring water.

Drosophila Melangogaster Experimental Group Preparation¶

D. melanogaster stocks were ordered from the Indiana Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center in September 2023. The flies used in this experiment were mutated after exposure to ethyl methanesulfonate by Bloomington before shipping. After the flies were transported to Burke County, NC, they were left to breed for 2 months. After each life cycle of a vial of fruit flies (containing ~20 fruit flies), larvae were transferred to a new labeled vial so they could lay new eggs. After the breeding period, flies were separated into 21 vials (1 for each experimental and control group), with ~12 flies per vial. Aqueous seed and leaf extracts were mixed into fly food at different concentrations depending on the treatment groups.

Table 1:D. melanogaster Experimental and Control Groups

| Extracts (3 vials of each) | Concentration |

|---|---|

| Control | 0 mg/mL |

| Leaf Extract | 2 mg/mL |

| Leaf Extract | 5 mg/mL |

| Leaf Extract | 10 mg/mL |

| Seed Extract | 2 mg/mL |

| Seed Extract | 5 mg/mL |

| Seed Extract | 10 mg/mL |

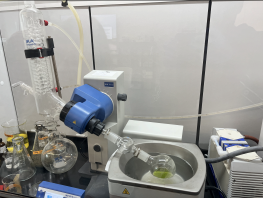

Figure 2:Fruit Fly Sample

After the flies had fed on their food either containing or lacking extract for a period of 3 weeks, they were sacrificed to collect tissue. Fly heads were cut off due to the high concentration of DSOR1 in the body. If the heads were included, the possibility to overload an assay increases as there is too much protein in 1 sample. DSOR1 was extracted from fly tissue through a process of heating the tissue mixed into RIPA buffer at 90℃ and extracting the supernatant from the heated microcentrifuge tubes. A total of 16 protein samples were collected.

Table 2:Protein Samples Collected From Fly Experimental and Control Groups

| Leaf Samples | Seed Samples |

|---|---|

| Control 1 | Control 1 |

| Control 2 | Control 2 |

| 2 mg/mL | 2 mg/mL |

| 2 mg/mL | 2 mg/mL |

| 5 mg/mL | 5 mg/mL |

| 5 mg/mL | 5 mg/mL |

| 10 mg/mL | 10 mg/mL |

| 10 mg/mL | 10 mg/mL |

Table 3:Nanodrop Protein Concentrations

| Leaf Samples | Protein Concentration (mg/mL) | Seed Samples | Protein Concentration (mg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control 1 | 21.103 | Control 1 | 29.712 |

| Control 2 | 31.376 | Control 2 | 35.040 |

| 2 mg/mL | 27.034 | 2 mg/mL | 31.724 |

| 2 mg/mL | 33.660 | 2 mg/mL | 23.211 |

| 5 mg/mL | 23.846 | 5 mg/mL | 32.728 |

| 5 mg/mL | 29.838 | 5 mg/mL | 29.087 |

| 10 mg/mL | 32.763 | 10 mg/mL | 32.539 |

| 10 mg/mL | 34.381 | 10 mg/mL | 35.873 |

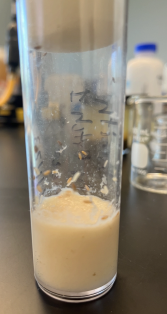

The Nanodrop protein concentrations fluctuate randomly due to the fact that this is the quantification for all protein inside of the flies, not just the target protein. To isolate the target protein, a western blot was run. The first step is to run a gel electrophoresis using a Bio-Rad protein gel instead of a DNA gel. This protein gel will capture the proteins in the membrane to create bands, similar to a DNA gel electrophoresis. The main difference is that proteins are captured on the gel to create bands instead of DNA. The leaf and seed samples are run on different gels with one devoted to just the leaf extract and one for the seed extract. A protein standard was used to create a reference for any other bands that may appear on the gel. The last lane is left empty to determine whether the gel is contaminated or sterile. A Tetra-Cell is used to run the gel electrophoresis and western blot.

Table 4:Description of Lanes on a Protein Gel for both Leaf and Seed Samples

| Lane | Sample |

|---|---|

| Lane 1 | Protein Standard |

| Lane 2 | Control 1 |

| Lane 3 | Control 2 |

| Lane 4 | 2 mg/mL |

| Lane 5 | 2 mg/mL (duplicate) |

| Lane 6 | 5 mg/mL |

| Lane 7 | 5 mg/mL (duplicate) |

| Lane 8 | 10 mg/mL |

| Lane 9 | 10 mg/mL (duplicate) |

| Lane 10 | Empty |

After the gel has run, a blotting sandwich created with blotting paper, filter pads, a nitrocellulose membrane paper, and the gel is placed inside of the Tetra-Cell to transfer the protein bands from the gel to the nitrocellulose paper so that antibodies can be added at a later step.

Figure 3:Image of Tetra Cell

After the protein bands have transferred from the gel to the nitrocellulose paper, antibodies are added to the paper and rocked. The membrane was incubated with 7 ml of blocking buffer for 45 minutes on a rocking platform. Blocking buffer was discarded and 7mL of primary antibody was added to the rocking platform and left to incubate for 1 hour. 7 ml of wash buffer was added to the membrane for 3 minutes on a rocking platform. The washing process was repeated two more times. The membrane was then incubated with 7 ml of secondary antibody for 1 hour. The membrane was rinsed in 7 ml of wash buffer 3 times for 3 minutes each. Wash buffer was discarded and 7 ml of HRP color detection reagent was added to the rocking platform to incubate for 10–30 minutes. The membrane was rinsed twice with distilled water and blotted dry with a paper towel. Finally, the paper was left to air dry for 30 minutes and then covered in plastic wrap. This process was done twice: once for the leaf gel and once for the seed gel.

Results¶

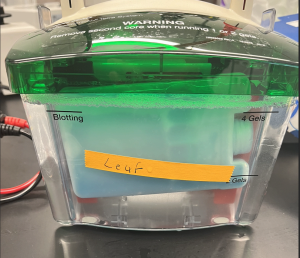

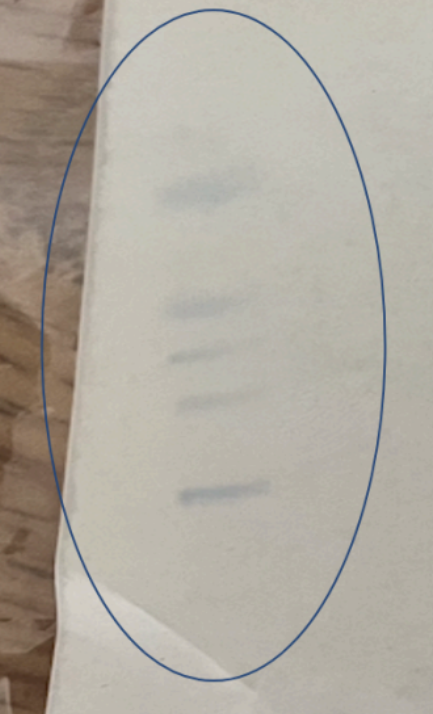

After running the western blots, the two air dried membrane papers were observed to determine the effects of M. oleifera on DSOR1 protein expression. However, the results were inconclusive as the blots did not show enough color to see any bands apart from the protein standard.

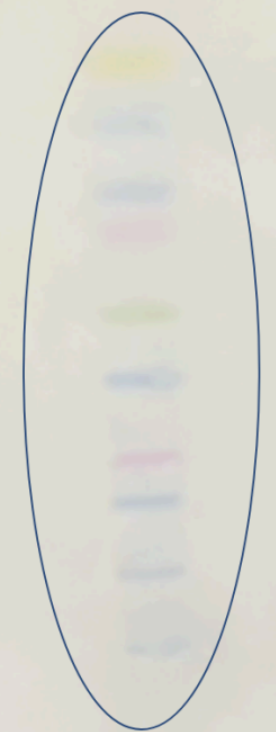

Looking at these two sheets, it is evident that the transfer process did not complete properly, leaving both sheets blank as they lack any bands of protein and only a faint ladder. For comparison, the image below shows the difference between the thickness and opacity of the bands on a nitrocellulose paper that had received the protein bands transferred properly compared to the leaf extract.

Figure 4:Leaf Sample Nitrocellulose Paper

Figure 5:Seed Sample Nitrocellulose Paper

It is clear that on a gel that was run properly, the bands have different colors, clear borders, and are easily visible and distinguishable. This likely means that the western blot did not run properly, and the effects of the treatment are not known.

Figure 6:Protein Bands on Leaf Sample

Figure 7:Protein Bands on Nitrocellulose Paper that Ran Properly

Discussion¶

Building on the results above and interpreting the factors that may have influenced the western blot, some possible reasons for why the blot malfunctioned could be determined. A likely issue could be the power supply for the Tetra-Cell that the Western Blot is run in. In the laboratory where the Western blot was performed, power is supplied to the Tetra-Cell through a surge protector that is connected to the wall. However, the surge protector lacks the ability to conduct enough voltage to properly power the Tetra-Cell. This causes the runtime of the blot to increase to account for the lower voltage. This affects how well the gel transfers to the nitrocellulose paper as low voltages or runtimes causes less of the paper to transfer.

The greatest possibility for error is in regards to the application of antibodies to the nitrocellulose paper after the Tetra-Cell was run. If too little antibody was poured onto the paper, there would not have been enough to bind to the target protein. Still, even if the antibody had binded to the protein, it wouldn’t be visible if the colorimetric agent did not visualize the bands on the paper. Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) was used in this experiment to bind to the primary and secondary antibodies, however, if the amount of HRP is too small, it will not be able to produce color on the paper because there isn’t enough to bind to the protein and create clear bands. This would mean that the antibodies could have binded to the target protein, but there is no visual information that justifies this theory, so the results are inconclusive.

Since the western blot was the issue, this also means that the effects of the treatment are unknown. Due to the fact that the Nanodrop quantifies the total amount of protein in each sample and not the target protein, the effects of seed and leaf extract cannot be identified because the target protein was not measured. If the experiment was to be repeated and the specific bands of protein were to appear on the western blot, ImageJ (a computer program to analyze an image of the western blot) could be used to quantify the amount of protein between samples and determine whether M. oleifera is a viable inhibitor of DSOR1 in fruit flies.

While the experiment had multiple issues, its successful aspects should be acknowledged as well. Due to the minimal amount of research dedicated to melorheostosis in humans and in medical models, the experimental methods described in this paper have not been performed before regarding the quantification of MEK1 protein in humans or DSOR1 proteins in fruit flies. This paper can be used as a proof of concept of how extracts can be taken from M. oleifera and used on D. melanogaster to inhibit protein expression. The nanodrop concentrations illustrate that M. oleifera can be exposed to fruit flies and proteins can be extracted from fruit flies with the methods described in this paper. The faint bands on the completed western blot cannot be used to definitively establish a link between the treatment groups and protein expression, but show that a minimal amount of protein was transferred through the gel. Under different conditions, this experiment could be replicated to produce results that can be analyzed.

Conclusion¶

Although the results of the western blot were inconclusive, the data gathered throughout the experiment is enough to draw conclusions and predict the efficacy of M. oleifera as a treatment for melorheostosis. On the positive side, proteins were able to be extracted from the fruit flies. This is shown by the Nanodrop protein quantification, which shows the total amount of protein in each sample. This means that the western blot itself was the confounding factor, as the process of breeding, feeding, and sacrificing fruit flies yielded enough protein to be quantified on a western blot. Utilizing another set of samples and the remaining tissue would allow the experiment to be repeated to possibly gain results.

After examining the possible errors that could have contributed to the inconclusive results, it is evident that much more future work should be done to answer the research question posed at the beginning of this experiment. Firstly, the western blot should be rerun with the proper conditions to accommodate the Tetra-Cell and the proper amount of antibody. Instead of using HRP as a colorimetric agent, fluorescence and a plate reader should be used to quantify the amount of protein on the nitrocellulose paper. This is beneficial for multiple reasons: a fluorescent agent will not deal with color that is visible to humans, which reduces the chance for a researcher to mistake the thickness and color of the bands due to bias. Using a plate reader to quantify the results will also be more accurate than a computer software analyzing an image because the photo quality, lighting of the picture, and angle could all be variables that affect the quantification of protein on ImageJ.

Beyond rerunning the experiment and fixing mistakes, in order to dive deeper into the potential of M. oleifera, running western blots with different experimental groups that change the concentration of extract and blots that change the samples in each lane will help determine whether leaf extract or seed extract is a better option. Furthermore, using these results, another extract could be created that combines the leaves and the seeds so that the synergistic effects can be tested against the extracts that are separate. Branching off from crude extracts, utilizing an isothiocyanate known as moringin to create an extract might be another possible solution. Moringin is located within the leaves and seeds of M. oleifera, and has been used in cancer research to test its inhibitory capabilities. With the inhibitory effects of isothiocyanates being a relatively new field of research, the use of moringin as an inhibitor for protein production and cell growth can prove to be useful, as a connection between inhibitory isothiocyanates and MAPK pathways has already been established in previous studies. Further than justifying the use of M. oleifera as a potential treatment option for melorheostosis, this future research can justify the use of isothiocyanates as an avenue for natural product drug development.

The author would like to thank the NCSSM Research in Biology Program, Mrs. Jennifer Williams, and Dr. Mareca Lodge.

Copyright © 2024 Gududuru. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, which enables reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the creator.

- HRP

- Horseradish Peroxidase

- NCSSM

- North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics

- Fick, C. N., Fratzl-Zelman, N., Roschger, P., Klaushofer, K., Jha, S., Marini, J. C., & Bhattacharyya, T. (2019). Melorheostosis: A Clinical, Pathologic, and Radiologic Case Series. American Journal of Surgical Pathology, 43(11), 1554–1559. 10.1097/pas.0000000000001310

- Vyskocil, V., Koudela, K., Pavelka, T., Stajdlova, K., & Suchy, D. (2015). Incidentally diagnosed melorheostosis of upper limb: case report. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 16(1). 10.1186/s12891-015-0455-z

- Kang, H., Jha, S., Deng, Z., Fratzl-Zelman, N., Cabral, W. A., Ivovic, A., Meylan, F., Hanson, E. P., Lange, E., Katz, J., Roschger, P., Klaushofer, K., Cowen, E. W., Siegel, R. M., Marini, J. C., & Bhattacharyya, T. (2018). Somatic activating mutations in MAP2K1 cause melorheostosis. Nature Communications, 9(1). 10.1038/s41467-018-03720-z

- Chou, S., Chen, C., Chen, J., Chien, S., & Cheng, Y. (2012). Surgical treatment of melorheostosis: Report of two cases. The Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences, 28(5), 285–288. 10.1016/j.kjms.2011.11.009

- Stratton, C. F., Newman, D. J., & Tan, D. S. (2015). Cheminformatic comparison of approved drugs from natural product versus synthetic origins. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters, 25(21), 4802–4807. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.07.014

- Chiș, A., Noubissi, P. A., Pop, O.-L., Mureșan, C. I., Fokam Tagne, M. A., Kamgang, R., Fodor, A., Sitar-Tăut, A.-V., Cozma, A., Orășan, O. H., Hegheș, S. C., Vulturar, R., & Suharoschi, R. (2023). Bioactive Compounds in Moringa oleifera: Mechanisms of Action, Focus on Their Anti-Inflammatory Properties. Plants, 13(1), 20. 10.3390/plants13010020

- Tshabalala, T., Ndhlala, A. R., Ncube, B., Abdelgadir, H. A., & Van Staden, J. (2020). Potential substitution of the root with the leaf in the use of Moringa oleifera for antimicrobial, antidiabetic and antioxidant properties. South African Journal of Botany, 129, 106–112. 10.1016/j.sajb.2019.01.029

- Wisitpongpun, P., Suphrom, N., Potup, P., Nuengchamnong, N., Calder, P. C., & Usuwanthim, K. (2020). In Vitro Bioassay-Guided Identification of Anticancer Properties from Moringa oleifera Lam. Leaf against the MDA-MB-231 Cell Line. Pharmaceuticals, 13(12), 464. 10.3390/ph13120464