Age Determination of NGC 1952 and PSR B0531+21 Using Radio Observations

Abstract¶

Supernova remnants (SNRs) and pulsars (PSRs) are highly related phenomena: Both can be produced from the same cosmic explosion. NGC 1952 and B0531+21, or the Crab SNR and PSR, are a verified pair. This research uses two strategies to estimate the ages of young SNRs and evaluates their reliability. The first strategy relies on the remnant’s expansion rate and radius to determine a convergence date. We operated the Green Bank Observatory 20-meter radio telescope in high-resolution mode to obtain spectra over a high-pass filter at a central frequency of 1420 MHz. While the data depicted a clear 21 cm hydrogen line, the Doppler calculation resulted in a meager expansion rate, which we found inadequate for subsequent age calculations. Second, due to the pulsar’s gradual loss of rotational energy over time, its period and period derivatives allowed us to extrapolate a formation date. We adjusted the telescope to low resolution at 1395 MHz. Age determinations reveal stages in SNR life cycles and support or disprove SNR-PSR associations. Several factors, including background radio interference, could impact the spectrum scans. However, the pulsar data produced an actual age within 50 years of the supernova’s verified explosion, confirming this method’s relative accuracy.

Introduction¶

Supernova remnants (SNRs) have been astronomical phenomena of interest since ancient times due to their brilliance in the visible spectrum. SNR events are evidenced in the artifacts of early civilizations. Records are believed to have begun in 185 C.E. Common type II supernovae occur due to the discontinuation of fusion in massive stars’ iron or nickel cores. However, in type III1 supernovae, the atomic nuclei of oxygen-neon-magnesium cores capture electrons. Both processes drive stellar collapse because of imbalances between gravity and pressure. Protons and electrons meld, forming a small, dense star supported by neutron degeneracy (more massive stars continue to collapse into black holes). Finally, this process produces a shock wave that expands inward and outward–expelling an array of gas and dust in the interstellar medium. Pulsars (PSRs), a form of a neutron star, rotate at extremely high velocities. Although they conserve much of their angular momentum, their periods gradually decline. Pulsars are detectable in gamma, x-ray, ultraviolet, or radio wavelengths due to the emission of synchrotron radiation from their magnetic poles.

A PSR’s characteristic age can be deduced from its period and derivative. The characteristic age assumes significant reductions in the initial period and an absence of magnetic field decay. Its accuracy indicates the relevance of these characteristics. The actual age, meanwhile, uses a pulsar’s braking magnitude and reveals whether multiple sources affect its spin-down.

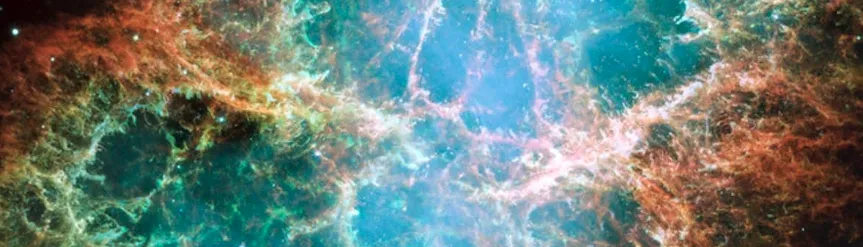

The Crab Nebula, a remnant of a supernova and a type III plerion located within the constellation Taurus, and its associated pulsar are the subjects of this research. Age determinations assist historians in connecting SNRs to Chinese records of “guest stars.” However, we focus on the Crab because of sufficient evidence from the year it was first observed, proving the accuracy of our results. Additionally, ages confirm pulsar associations: A pulsar may gradually drift from a remnant’s center Condon, 2017. We compare two methods in their effective determination of the Crab SNR’s age: The first utilizes the remnant’s expansion, and the second relies on the spin properties of its pulsar.

Figure 1:An optical image of the NGC 1952 taken by the Hubble Space Telescope in 2005. The central glow highlights the pulsar.

Methods¶

Initially, our research relied on the operation of the Pisgah Astronomical Research Institute’s 12-m radio telescope. We sought to measure the diameter of the remnant using multiple continuum scans. However, the telescope could not produce these scans due to the SNR’s uneven distribution of hydrogen gas, nor was its data acquisition system designed to detect fast pulsars.

Radio Observations¶

The Green Bank 20-m radio telescope with an L-band receiver (1.15-1.73 GHz) was used for all original observations.

Table 1:A summary of completed observing runs for the supernova remnant NGC 1952 and pulsar B0531+21.

| Run | Object | Coordinates and Apparent Magnitude | Time of Observation (UT) | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NGC 1952 | RA 05:35:54.67 DEC 22:01:49.1 Mag. 8.4 | 17:51:05 | 2023-06-27 |

| 2 | NGC 1952 | RA 05:35:54.67 DEC 22:01:49.1 Mag. 8.4 | 21:02:37 | 2023-07-01 |

| 3 | B0531+21 | RA 05:34:31.9 DEC 22:00:52.1 Mag. 16.5 | 19:00:04 | 2023-07-24 |

| 4 | B0531+21 | RA 05:34:31.9 DEC 22:00:52.1 Mag. 16.5 | 20:01:56 | 2023-07-25 |

| 5 | B0531+21 | RA 05:34:31.9 DEC 22:00:52.1 Mag. 16.5 | 19:09:29 | 2023-07-26 |

Telescope Settings: SNR Data¶

We produced two spectrum scans of the Crab SNR to estimate its expansion rate. This approach relied on measuring the Doppler shift of the hydrogen 21 cm emission line (with a precise frequency of 1420.406 MHz) and assumed that the shell had undergone no acceleration while dispersing from a point. The pulsar’s energy input, combined with the shell’s evolving interaction with the interstellar medium, would cause numerous complications Brandt & Williamson, 1979. We pulled frequency values from the minimum coordinates of the spectral features displayed by our scans and averaged the corresponding pairs. We then substituted these values into Equation (1) to find a velocity difference for the slightly redshifted and blueshifted radio waves (due to the nearer approaching side of the shell and the further receding side). Finally, with measurements for the expansion velocity, we aimed to estimate a convergence date from the radio size of the remnant.

Telescope Settings: PSR Data¶

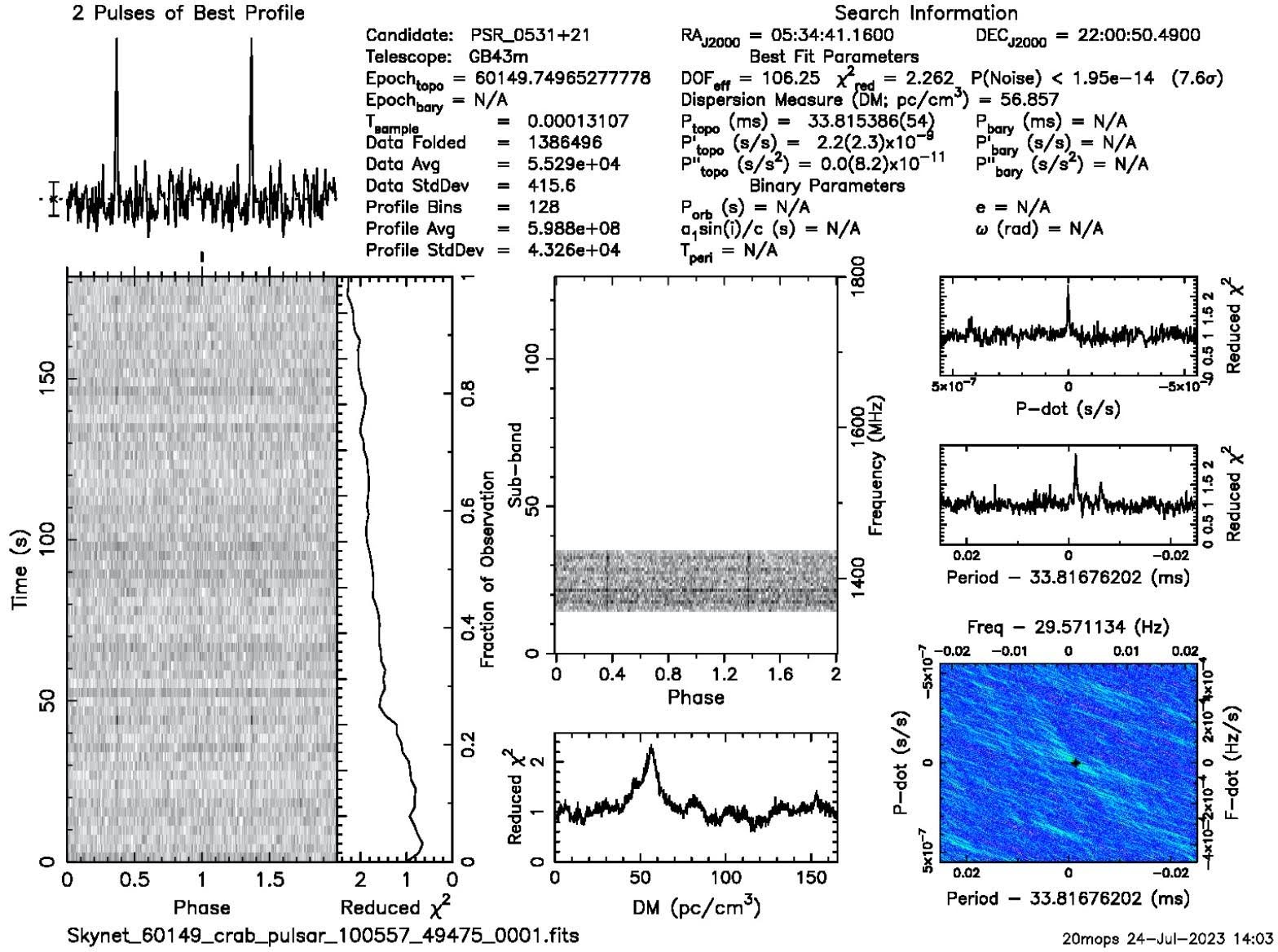

We conducted three scans of PSR B0531+21, as described in Table 2, to determine the approximate period. Green Bank’s systems produced the data in processed Prepfold Plots Figure 2. Due to the spin-down of the pulsar, the period, , gradually decreases over many years. The period derivative, , describes this change. We found using the Prepfolds, as well as a recorded period from the Jodrell Bank Observatory in 1982 Lyne & Tong, n.d..

Table 2:Control parameters for all telescope observations.

| Setting | NGC 1952 | B0 531+21 |

|---|---|---|

| Receiver Mode | Highres | Lowres |

| Central Frequency (MHz) | 1420 | 1395 |

| Filter | HI | HI |

| Pattern | Track | Track |

| Duration (sec) | 60 | 180 |

| Integration Time (sec) | 0.5 | 0.0001 |

| Number of Channels | 1024 | 1024 |

| Min. Sun Separation (degrees) | 12 | 0 |

| Min. Elevation (degrees) | 20 | 20 |

Characteristic and True Ages¶

We calculated the characteristic age, denoted , using Equation (2), which required only the period and period derivative.

With Equation (3), we then estimated the true age, τ. Unlike the characteristic age, the true age of a pulsar incorporates , the magnetic braking index or the loss of rotational energy due to ionized material traveling along the pulsar’s magnetic field lines, and , the initial period upon the formation of the pulsar.

A differentiated and rearranged form of Equation (4), which describes the relationship between the period, the constant, , and the braking index, allowed us to solve for : . The derivations of and require complex models actively being explored. The process is further complicated by numerous glitches or random and disruptive spin-up events experienced by the Crab PSR. However, recent studies have given estimates for Zhang et al., 2022, as well as Malov, 2017 between glitches: values which we use here.

Results¶

SNR Rate of Expression¶

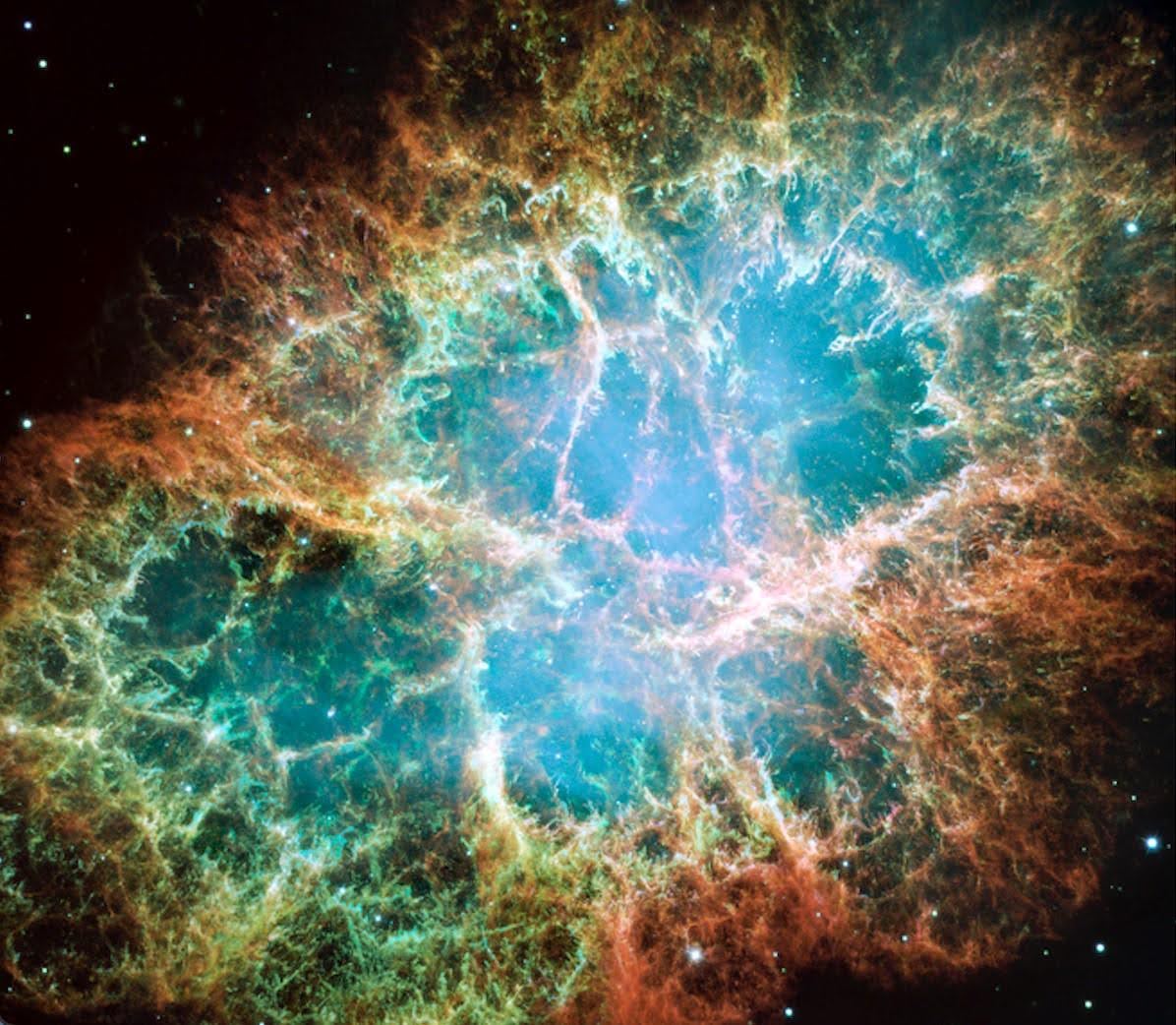

The Crab remnant is composed primarily of hydrogen gas. Neutral hydrogen produces the 21 cm line, which is evident as a sharp emission feature around 1420 MHz Figure 2. The 21 cm undergoes slight dispersion in energy and quickly passes through the Earth’s atmosphere, making it observable with little interference. The averages of the spectral features’ minima, 1420.16 MHz and 1420.67 MHz, resulted in a total expansion velocity of 108 km/s.

However, the data may have been skewed by various factors. For example, it is possible that the sharp peak was produced by background sources and not the composition of the remnant itself. The Crab SNR has a relatively small angular size (4-8 arcmin) compared with the telescope’s wide field of view. We did not produce further scans due to these significant uncertainties, nor did we carry out subsequent age calculations. Yang & Chevalier (2015) estimate that the velocities of most shell features range approximately between 1260-1700 km/s. “Daisy” telescope scans process the sky surrounding an object, allowing the observer to discern radio-emitting sources within a set radius. We may implement this method in future trials to recognize sources of error.

Figure 2:A spectrum scan from observing run 1 displaying the linearly polarized components of the signal ( and ), plotted as power () versus frequency (MHz).

PSR Period, Braking, and Age¶

The pulse profile (top left of Figure 3) represents the period produced from folded data and reveals recurring signals. The three measurements resulted in an average period of 0.0338149930 seconds. Thus, with the February 15, 1982 record of 0.0332676584 seconds, we found the period derivative to equal .

Figure 3:A pulsar dataset (compiled by Green Bank into a Prepfold Plot) depicting a regular, well-defined signal from observing run 3.

Characteristic Age¶

We determined the characteristic age to be seconds or 1280.9 years. For millisecond pulsars, the characteristic age can be many times greater than the actual age, which indicates that is similar to . Although the approximation above is reasonable, the actual age demonstrates higher accuracy. Using Equation (4) and a period second derivative of , was found to be 2.52. The braking index is slightly less than the expected value of 3 if the spin-down were due solely to magnetic dipole radiation; therefore, other factors contribute to the pulsar’s loss of rotational velocity Kou & Tong, 2015.

True Age¶

Utilizing Equation (3) and a value of 0.0183 seconds for

Chinese Sung Dynasty astronomers described the remnant in the Sung Shih annals, and the Japanese documented it in the texts Mei Getsuki and Ichidai, stating, “It shone like a comet and was as bright as Jupiter” Brandt & Williamson, 1979. It is also evidenced in a pictographic representation of the ruins of the Anasazi’s Peñasco Blanco.

Discussion and Conclusion¶

Age determinations derived from spectrum scans of the Crab SNR’s radio expansion velocity are impacted by the remnant’s competing traits and the likelihood that most of the nebular ejecta does not move directly toward or away from Earth. Considering the possibility of radio frequency interference (RFI), the expansion velocity could be measured more accurately in the visible spectrum. Published high-resolution photographs taken across several decades could also account for the velocities of individual knots. However, Nugent (1998) notes that their optical velocity closely agreed with other published research, indicating a convergence date 76 years after the 1054 C.E. supernova. Meanwhile, Bietenholz & Nugent (2015) determined that the Crab’s inner “synchrotron-emitting bubble,” detectable on the radio, expands faster than the outward optical filaments. They reached this conclusion and accounted for the remnant’s less prominent features by applying unique scaling techniques to high-resolution radio and optical photographs. The results of the spectrum scans presented here support the need for advanced observing techniques that capture the remnant’s asymmetrical geometries and dynamic physical properties.

Meanwhile, despite undergoing glitches, pulsars’ compact structures and the benefits of folded data in distinguishing recurring signals from RFI contribute to very accurate time of arrival measurements. We encounter problems considering that many young SNRs do not contain detectable pulsars – perhaps because these pulsars do not emit signals that can be discerned among the remnant’s intense radiation. However, at least 20 pairs of plerions and pulsars are known with certainty to exist. Our research conveys that pulsars provide valuable insight into the age and evolution of SNRs. In contrast to expansive nebulae and supernova ejecta, the properties of pulsars make them a very reliable tool for astronomers.

The research presented in this paper was made possible through the generous allocation of resources and equipment by the Green Bank Observatory. I thank Tim DeLisle and Melanie Crowson at the Pisgah Astronomical Research Institute for their invaluable guidance in operating radio telescopes. Additionally, I appreciate James Happer, a physics instructor at The North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics, for his assistance during the initial stages of brainstorming research topics and for providing valuable suggestions in analyzing spectrum data. I also thank Jacob Brown for his insightful advice regarding potential sources of error.

Copyright © 2024 Covington. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, which enables reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the creator.

- PSR

- Pulsar

- PSRs

- Pulsars

- RFI

- radio frequency interference

- SNR

- Supernova remnant

- SNRs

- Supernova remnants

- Condon, J. J. (2017). Essential radio astronomy. Contemporary Physics, 58(3), 278–279. 10.1080/00107514.2017.1312538

- Brandt, J. C., & Williamson, J. C. (1979). The 1054 supernova and native American rock art (Vol. 10). Journal for the History of Astronomy, Archaeoastronomy Supplement.

- Lyne, A., & Tong, H. (n.d.). CRABTIME - Crab Pulsar Timing. https://heasarc.gsfc.nasa.gov/W3Browse/all/crabtime.html

- Zhang, C.-M., Cui, X.-H., Li, D., Wang, D.-H., Wang, S.-Q., Wang, N., Zhang, J.-W., Peng, B., Zhu, W.-W., Yang, Y.-Y., & Pan, Y.-Y. (2022). Evolution of Spin Period and Magnetic Field of the Crab Pulsar: Decay of the Braking Index by the Particle Wind Flow Torque. 10.48550/ARXIV.2212.04674

- Malov, I. (2017). On the second derivatives of the spin periods and braking indices in radio pulsars. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 468(3), 2713–2718. 10.1093/mnras/stx619

- Yang, H., & Chevalier, R. A. (2015). Evolution of the Crab nebula in a low energy supernova. 10.48550/ARXIV.1505.03211

- Kou, F. F., & Tong, H. (2015). Rotational evolution of the Crab pulsar in the wind braking model. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 450(2), 1990–1998. 10.1093/mnras/stv734

- Nugent, R. L. (1998). New Measurements of the Expansion of the Crab Nebula. Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 110(749), 831–836. 10.1086/316199

- Bietenholz, M. F., & Nugent, R. L. (2015). New expansion rate measurements of the Crab nebula in radio and optical. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 454(3), 2416–2422. 10.1093/mnras/stv2112